Divine Light – The Stained Glass of England’s Cathedrals – The Long Nineteenth Century 1800 to 1920

A renewed interest in stained glass, led by antiquarians and collectors, instigated its return to cathedral interiors. As we have already seen, in 1805 the existing East Windows at Lichfield were glazed with sixteenth-century glass from a former Flemish convent.

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Following a period in which medieval taste was recreated somewhat impressionistically, the Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century adopted a more scholarly, historical approach. This movement was led by architect A.W.N. Pugin, who collaborated with but eventually parted ways from Thomas Willement (St George’s Chapel, Windsor), William Warrington, and William Wailes (Chemist’s Window, Newcastle) before his successful collaboration with John Hardman (Worcester West Window by Hardman’s nephew John Hardman Powell). Willement led the return from a painterly approach in glass window production to leading coloured pieces of glass and framing figures in architectural canopies. This shift coincided with a desire to conserve medieval glass – old and new glass would often be brought together in the same window.

From the 1840s onwards, there was a general move away from treating churches as clear-glazed Protestant preaching boxes in favour of a more sacramental and ritualised form of worship. This partly accounts for an explosion of interest in coloured-glass windows, which often had a strong biblical narrative dimension. Many nineteenth-century windows were commissioned as memorials, and consequently the involvement of patron, clergy and architect is evident in the selection of subject matter and iconography. Large narrative schemes were developed for cathedrals such as Truro (by Clayton & Bell) and Wakefield (by C.E. Kempe).

A group of Pre-Raphaelite artists reacted against the nineteenth-century commercialisation of glassmaking and formed Morris & Co. Bradford Cathedral has early Morris & Co. windows, which inspired Heaton, Butler & Bayne’s Women of the Bible Window (also in Bradford Cathedral). Pre-eminent among the Pre-Raphaelite stained-glass artists was Edward Burne-Jones, who worked with William Morris to produce four windows for the remodelled church that became Birmingham Cathedral, culminating in Burne-Jones’s Last Judgement masterpiece.

Concern about the separation of the artist from the production of glass manifested itself in the Arts and Crafts Movement. We see both Henry Holiday (at Chelmsford) and Christopher Whall (in the Lady Chapel at Gloucester), the latter of whom was a mentor to several other artists, making and using their own artisanal – often ‘slab’ – glass. Other nineteenth-century innovations included opalescent glass of the kind used by US glassmaker John La Farge – a rare example inthe UK exists at Southwark Cathedral. Women glassmakers were also emerging during this period, most notably Veronica Whall, who worked with her father at Gloucester, and Mary Lowndes, who established the Glass House studio in Fulham.

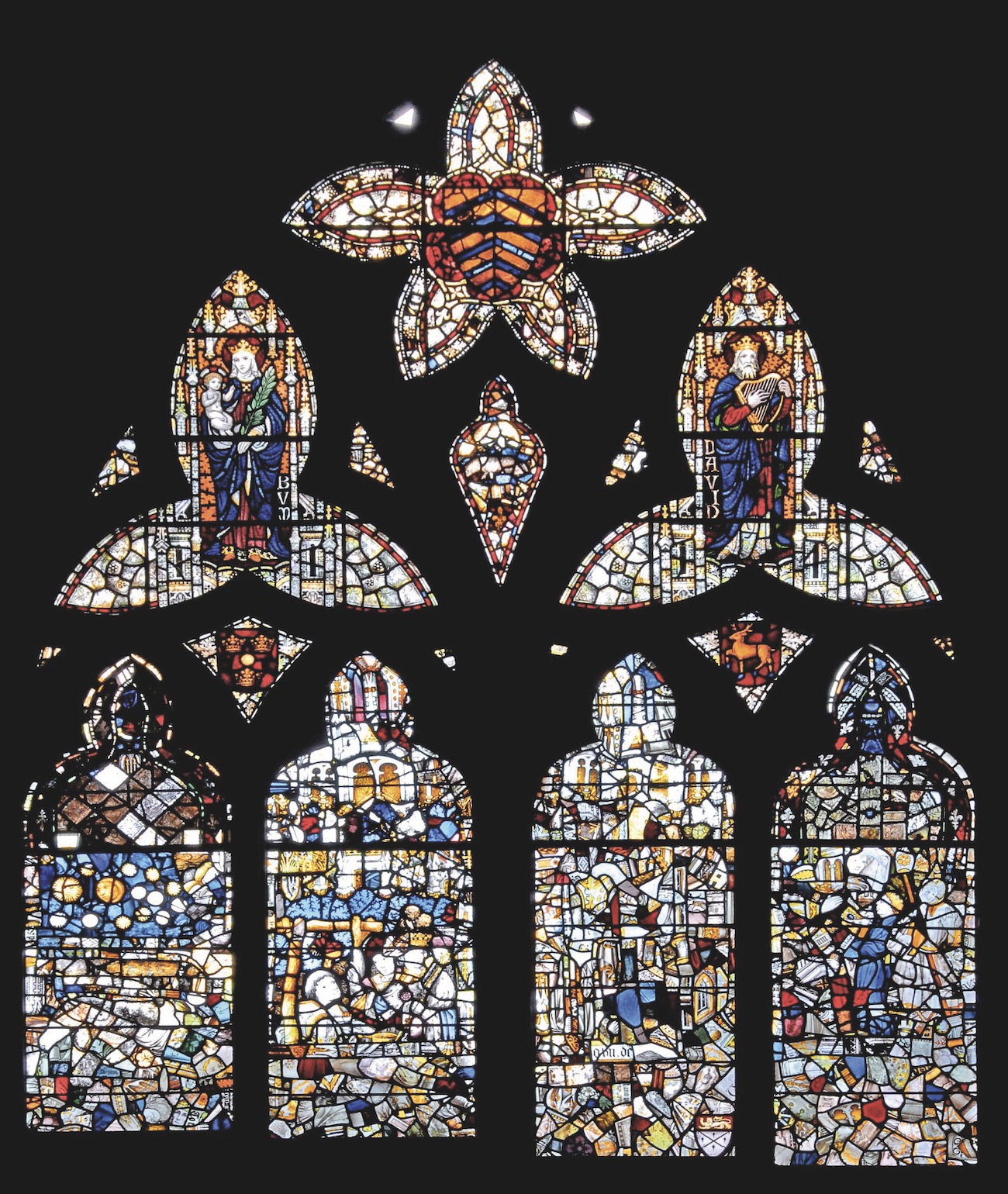

HEREFORD CATHEDRAL – Patchwork Window (created by 1835)

Four-light window including fragments of fifteenth-century glass, south nave aisle, 5 × 3.75 m

Hereford Cathedral has many fine ancient and modern stained-glass windows, but some of the most interesting take the form of what the Cathedral’s archivist refers to as ‘patchwork’ windows. Comprising fragments of medieval glass, these windows’ jumbles of colours and juxtapositions of random images and lettering make for an eye-catching and oddly satisfying whole.

The identity of the person who commissioned the south nave aisle window has been lost to history, but the window is nonetheless full of rich and tantalising hints regarding the story behind it. The four lights consist of fragments of fifteenth-century glass depicting scenes from the life of Joseph. Discernible are Joseph’s dream of the sun, moon and stars, of wheatsheaves bowing down to him, and Joseph being bundled into a pit by his brothers (Genesis 37:9, 5–7, 23–4). There is also older tabernacle work and ornate borders to admire. Even though the window does not show a complete image, the overall effect is delightfully colourful and charming and can keep an attentive observer busy for hours. There are further fragments of glass, believed to be left over from the creation of this window, in the Cathedral’s collections.

Above the patchwork, there are more modern compositions in the trefoil tracery showing David with his harp and the Blessed Virgin Mary cradling Jesus in her arms. More prosaically, in the cinquefoil tracery are the ancient arms of deanery and diocese.

A former dean has described this window as ‘a parable of seeing God through tiny glimpses’. The fragments may not make much sense in isolation, but they add up to a rich image of glory and hint at things not yet understood. For the pilgrim, the act of seeking a narrative within disparate pieces can be a strangely personal and profound experience.

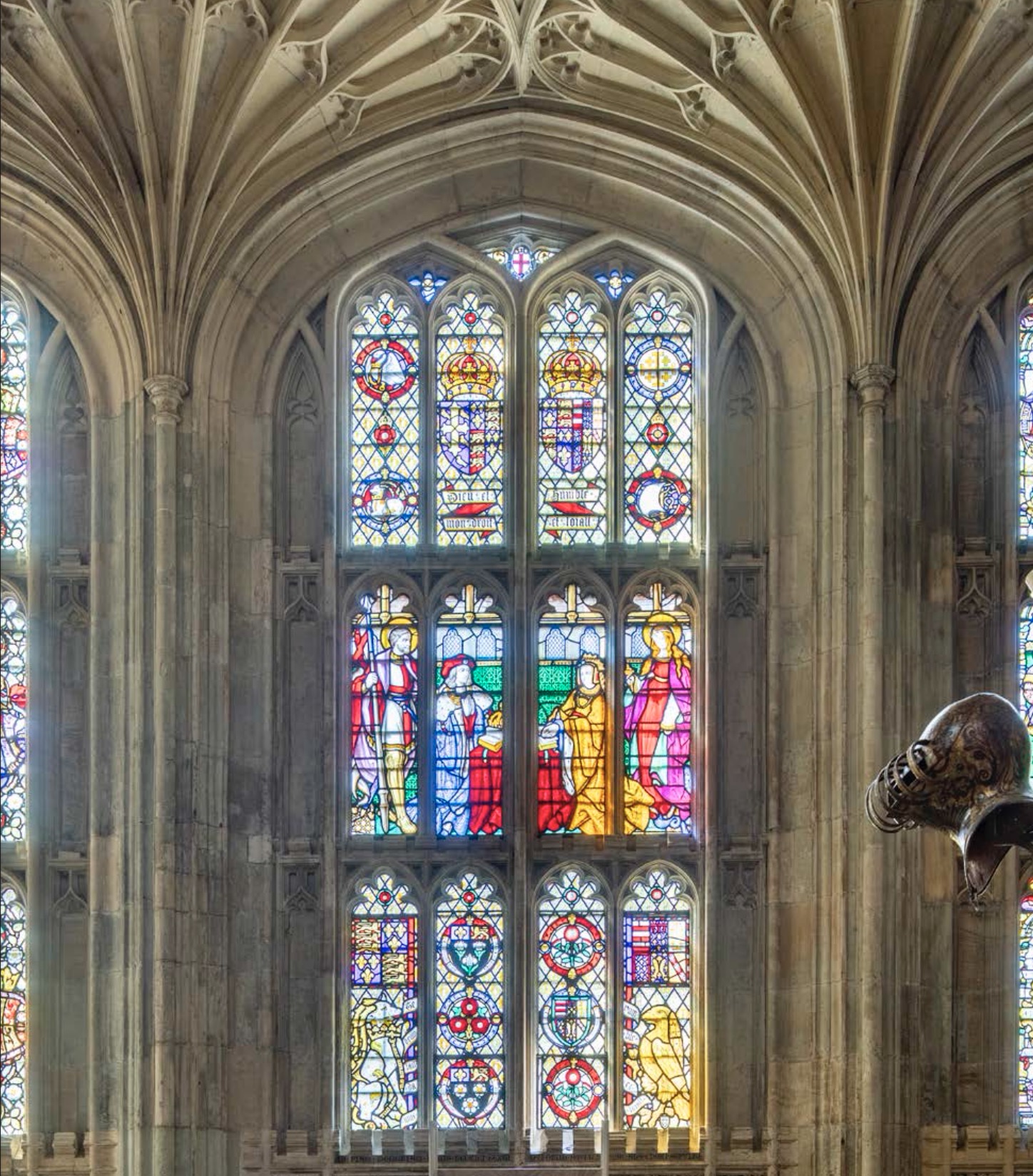

ST GEORGE’S CHAPEL, WINDSOR CASTLE – The Stained Glass of Thomas Willement (1840–61)

Heraldry windows in quire clerestory, history of English monarchy and Church in quire aisles, and restoration of the West Window, all by Thomas Willement (1786–1871), quire aisle, each window 5.1 × 1.5 m

Thomas Willement’s connection with St George’s Chapel lasted for twenty-one years. He was initially engaged to restore the Chapel after the removal of eighteenth-century limewash from the walls revealed medieval paint underneath. Willement had a deep interest in heraldry, and his work at Windsor allowed him to indulge his enthusiasm.

The first windows which Willement made for St George’s are in the quire clerestory, and each simply contains the coat of arms of a Garter Knight with a crest and mantling.

The quire aisle windows depict kings and queens from Edward III to William IV. These figures are presented in their ecclesiastical contexts: Henry VIII and William IV are shown with the emblems of the new bishoprics that they created. Many of these monarchs are buried in the Chapel, but it is interesting to note which monarchs Willement did not choose to feature. His version of royal history removes various contentious elements, and so Mary I is omitted entirely (one window shows Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, Edward VI and Elizabeth I), James II only appears as a child in Charles I’s window, and Richard III is nowhere to be seen.

The window depicting Edward III – founder of the Order of the Garter – shows him alongside his wife, Philippa of Hainault. A seventeenth-century illustration provided the model for Edward; Philippa was modelled on a drawing of a fourteenth-century depiction of her on the east wall of St Stephen’s Chapel Westminster, which by Willement’s time had been destroyed.

Although there are religious elements in these windows, they could fit just as easily into a palace. The impression projected by the heraldic and figural windows is one of royal power and continuity in a chapel focused on the Order of the Garter.

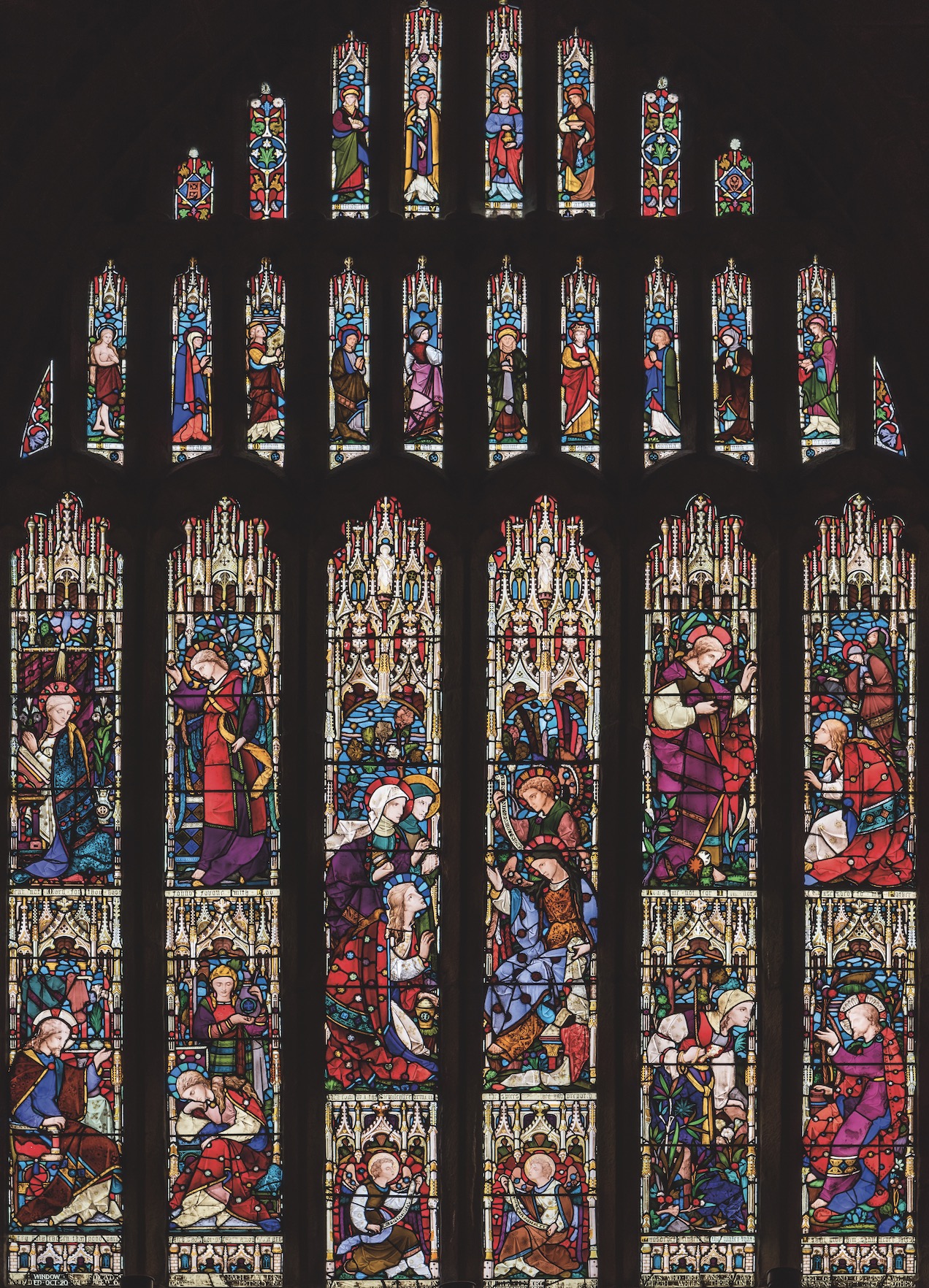

BRADFORD CATHEDRAL – Women of the Bible West Window (1864)

Biblical scenes featuring women in naturalistic poses and vivid colours, Robert Turnill Bayne (1837–1915) and Alfred Hassam (1842–69) for Heaton, Butler & Bayne, c.4 m wide

Bradford Cathedral’s magnificent West Window by the firm Heaton, Butler & Bayne, consisting of designs by Robert Turnill Bayne and Alfred Hassam, is a favourite of staff and visitors alike.

It was commissioned in 1863 to commemorate Catherine and Jane Wells, the two sisters of a Bradford solicitor called William Wells, which is probably why the window almost exclusively features women. There are female figures from the Old and New Testaments in its top two panels and five episodes from the New Testament in its main panels, each of which portrays women experiencing the extraordinary presence or call of God as they go about their daily routines.

This beautiful Pre-Raphaelite window is vibrant with colour even on the dullest of days. Hassam’s use of purple, often in combination with red, is particularly striking. The window is also notable for the naturalism of its figures; it shows pairs or groups of figures engaged in conversation and making lifelike poses and gestures. There are also distinctive background details, particularly in the lower right panel, which depicts Christ and the Samaritan woman standing by a well (John 4:4–42), with foliage springing up from where water has splashed on the ground.

The five main panels present: the Angel Gabriel greeting the Virgin Mary (top left); Mary Magdalene being greeted by the risen Christ (top right); Jesus with the sisters Mary and Martha of Bethany (lower left); Jesus speaking with the Samaritan woman at the well (lower right); and the angels telling the women the news that Jesus is risen, on Easter morning (centre).

NEWCASTLE CATHEDRAL – Chemist’s Window (1866)

The so-called ‘Chemist’s Window’, dedicated to Joseph Garnet, may appear unremarkable at first glance, but a remarkable story lies behind it. Garnet, a chemist with a shop on a nearby street called Side, was a devoted member of St Nicholas’s Church (now Newcastle Cathedral). He passed away in 1861, and only after his death did the full extent of his quiet philanthropy become known. Garnet had used his time and resources to help many in need, and in recognition of his selflessness his friends – who had worshipped at St Nicholas’s alongside him – raised funds for a window in his memory.

The window’s design is inspired by the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats from the Gospel of Matthew (25:31–46), where Jesus teaches that judgement will be based on how we have served the poor, hungry and imprisoned – on whether we have seen Christ in the least among us.

What makes the ‘Chemist’s Window’ striking is that the face of the person helping those in need is always that of Joseph Garnet himself. The backdrop includes his chemist’s shop and the street where he lived.

The window was created in the studio of William Wailes, a prominent artist whose stained-glass workshop in Newcastle was one of the largest and most prolific in England. The window was removed after being damaged during enemy action in 1941 and was subsequently held in storage, with some considering its sale in 1973. But in 1980 the Pharmaceutical Society sponsored the window’s reinstatement, which was overseen by the Cathedral architect, Ronald G. Simms. The glass was reset and placed against clear leaded glazing.

The window’s powerful scenes challenge us to reflect: could we place our own faces and our own streets in this narrative of service and compassion.

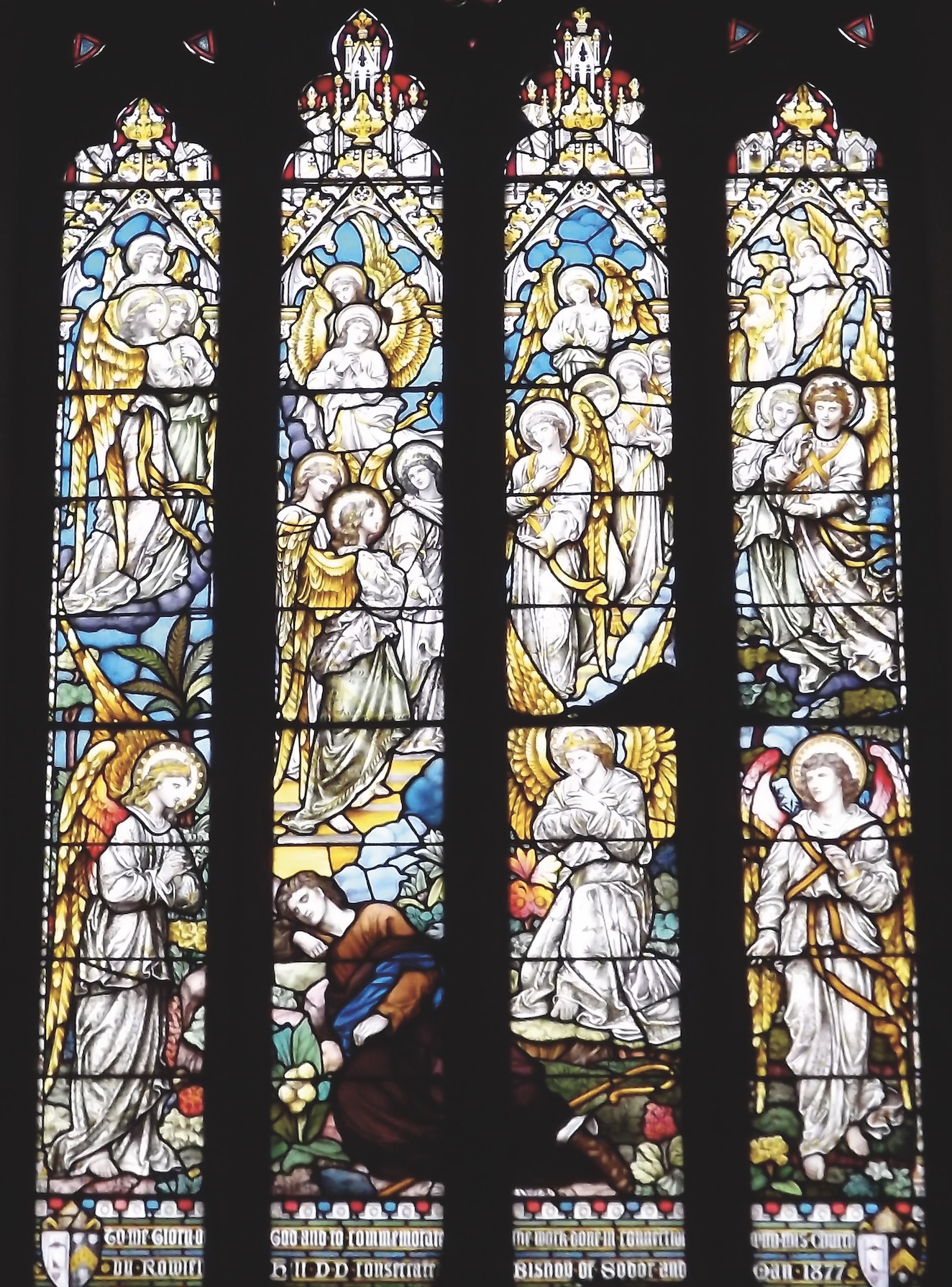

ST GERMAN’S CATHEDRAL, ISLE OF MAN – Jacob’s Ladder or Bethel Window (1878)

Designed by Alexander Gibbs (1832–86) and made by Alexander Gibbs & Co. of Bloomsbury, north transept, 6.3 × 2.5 m

The story of Jacob’s ladder (Genesis 28:10–19) is portrayed in the North Transept Window of St German’s Cathedral, which was installed as a memorial to Rowley Hill, Bishop of Sodor and Man from 1877 to 1887. The glass is predominantly yellow on an elevation of the Cathedral that receives no sun.

Bishop Rowley complained that he was the only diocesan bishop in the Church of England without a cathedral (although there was the ancient Cathedral in ruins on St Patrick’s Isle off Peel). He set about rectifying this situation by building a new Cathedral in Peel. He struggled to finance the building work on an island where there were high levels of churchgoing but also high levels of poverty.

He therefore went on tours, preaching around England to enable the realisation of his vision. The stress of building St German’s and the huge political opposition he encountered is reported to have been the death of him; he died aged fifty-one, years before the necessary legislation was passed by an Act of Tynwald. Ninety-three years after his death, in 1980, Bishop Rowley’s vision was finally implemented.

The background to the story depicted by the window is Jacob’s having fled from his brother Esau, whom he has just defrauded of their father’s blessing. He finds a place to sleep for the night and receives a remarkable dream that suggests to him that the spot on which he has been sleeping is the gate of heaven. When he awakes he is awestruck by this experience and renames the place ‘Bethel’, which means ‘House of God’.

In the Celtic world, people often speak of ‘thin places’ – locations where the veil between heaven and earth is almost transparent. For many worshippers, St German’s is just such a place.

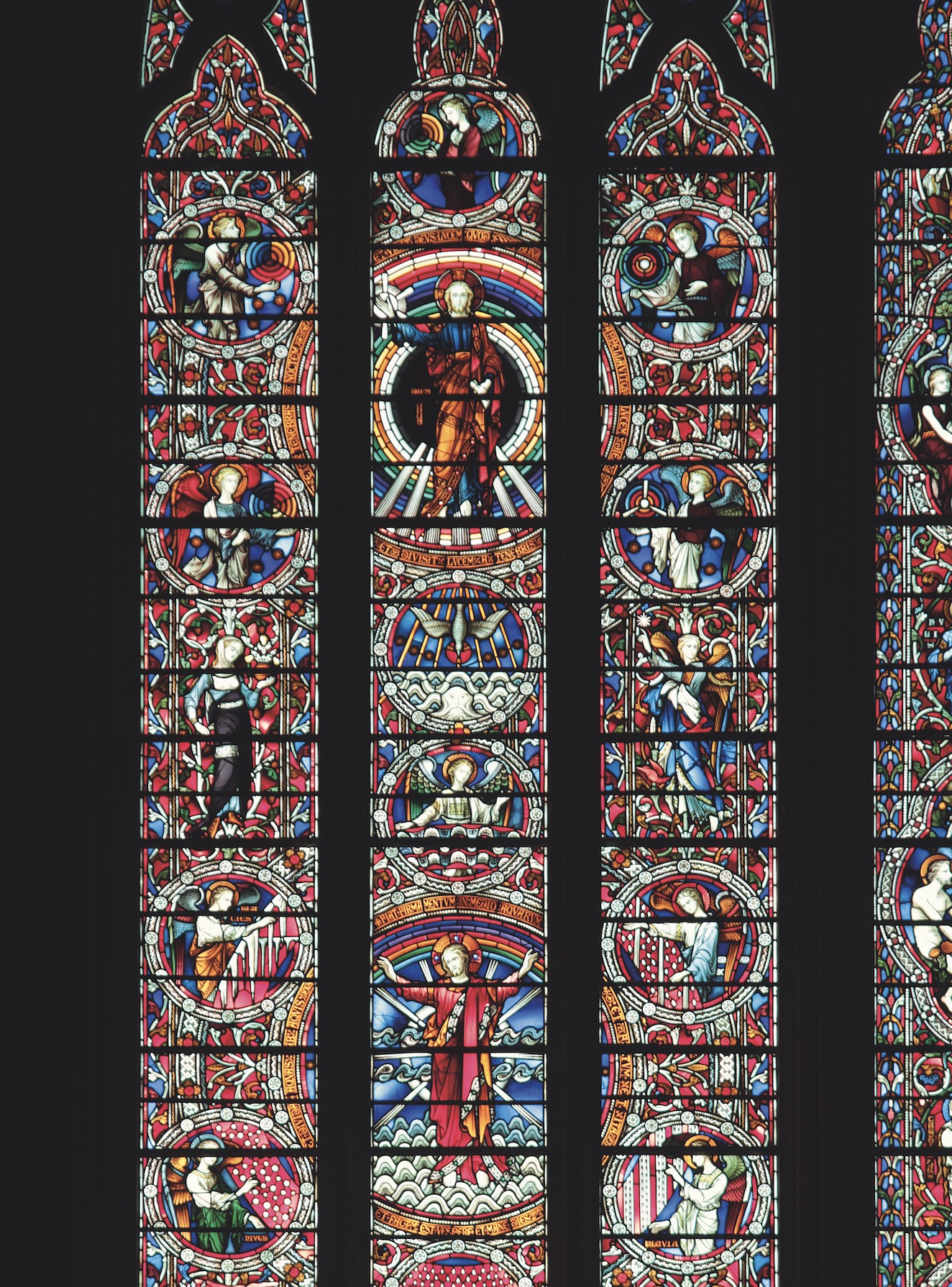

WORCESTER CATHEDRAL – Creation and Fall West Window (1875)

Eight vertical lights (each 8.6 × 0.7 m) with brightly coloured glass in medallions; tracery and rose window (diameter 4.2 m) above; designed by John Hardman Powell and made by Hardman & Co. of Birmingham.

Recently restored and cleaned, this glorious window fills the west wall of the nave. It was gifted by Lord Dudley as part of the great restoration of the Cathedral in the late nineteenth century and was produced by the world-leading Birmingham-based firm Hardman & Co., whose principal designer John Hardman Powell was the protégé and son-in-law of the Gothic Revivalist A.W.N. Pugin. Its Flowing lines, roundels, Curvilinear figures and gorgeous colours – including a now famous pink giraffe – were evidently inspired by thirteenth- and fourteenth-century glass.

The window is based on the Book of Genesis; its eight main vertical lights tell the story of the Creation and the Fall. The large roundels depict the first six days of the Creation, and the upper and middle sections contain scenes of the expulsion from Eden and of life after the Fall. Each large roundel is surrounded by six smaller roundels expanding on its theme in strikingly vivid and innovative ways.

Alongside the six-day story of Creation there are also scenes depicting the elements, images contrasting virtues with vices, and panels showing the seasons. The quatrefoils at the head of alternate lights show the four winds. At the top of the window, the wheel constructed in Geometric style as a rose within the tracery portrays God Almighty surrounded by angels with musical instruments. The other tracery lights show angels in various scenes of adoration, or abstract foliate designs.

The pink giraffe has quite a following. She has been known as Georgina for many years and continues to bring wonder and amusement to visitors to the Cathedral. The quality of the glass, design and execution is exquisite, and as the light changes with the hours and the seasons, Georgina takes her place in the joyful glass of Worcester’s largest window.

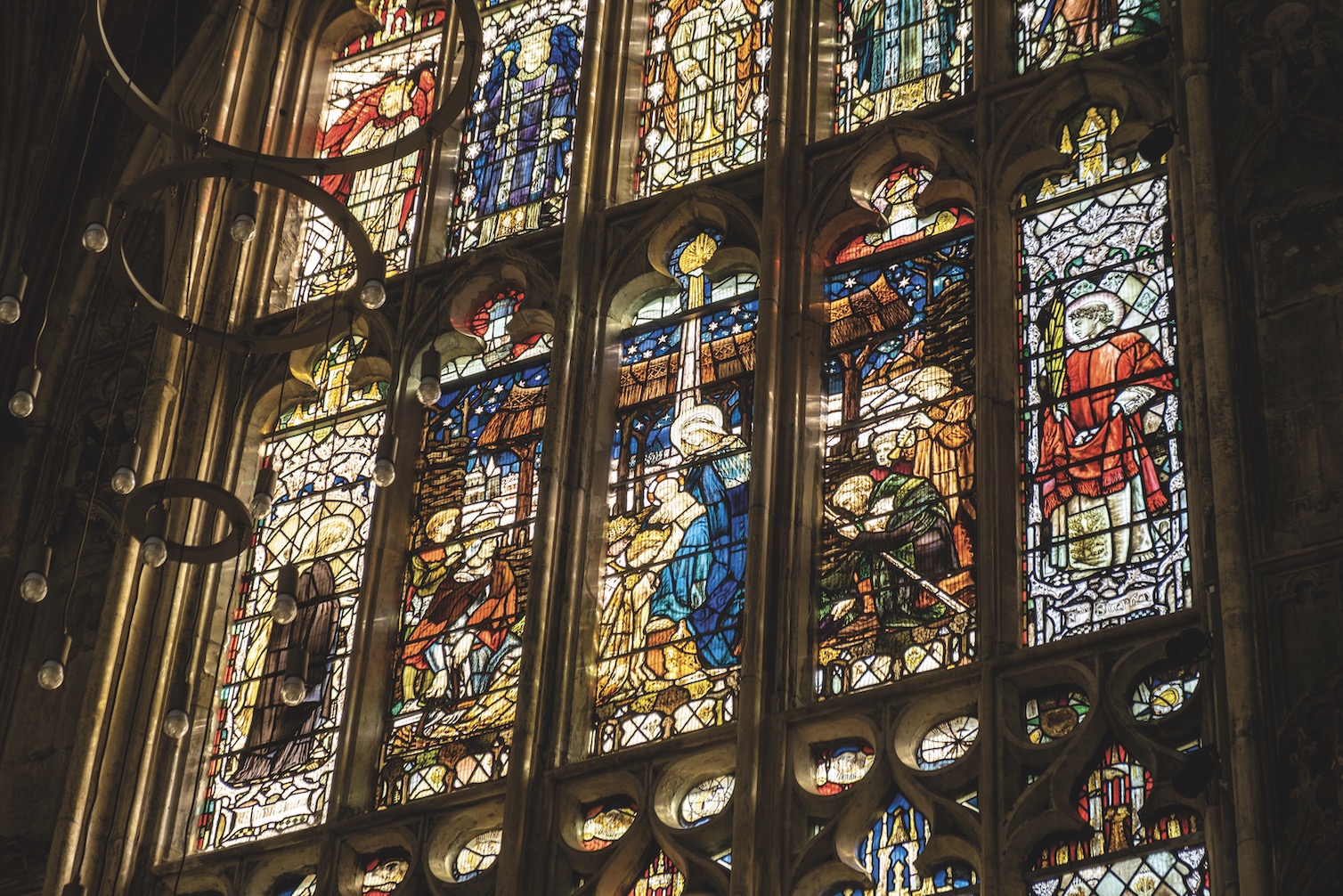

TRURO CATHEDRAL – Glazing Master Scheme (1887–1910)

Ambitious single-studio scheme of eighty windows (c.300m2) by Clayton & Bell, conceived for new cathedral by Edward White Benson (first Bishop of Truro 1877–83)

Truro Cathedral’s unified glazing scheme affords a remarkable insight into the High Victorian mind. It tells us what, at the height of Britain’s imperial power, the man who was soon to become Archbishop of Canterbury regarded as the vital lessons to be learned from history.

Bishop Edward White Benson was appointed in 1877 to a new diocese without a cathedral. He seized the possibilities offered by this unique and astonishing opportunity – a completely blank canvas.

The architectural competition he launched was won by a romantic Gothic Revival design. Three magnificent rose windows and the great windows of the quire confidently asserted the Christian faith of the Trinity and Gospels. Then, using a single stained-glass studio, Clayton & Bell, Benson and his confidants carefully selected 108 historical characters – people whose faith shaped what they did, and whose actions changed the face of Europe and beyond – to be portrayed in stained glass. Woven into the sequence are local industries and ten Cornish notables, entirely appropriate for ‘Cornwall’s cathedral’.

Through the prism of a striking selection of characters (including Charlemagne, Joan of Arc, Thomas More and Isaac Newton), Christianity emerges from Truro’s windows not as an impediment to, but as a driver of, progress. The windows present an alternative history to the standard version we receive today, focused not on nations, war or technological change, but on the motivational force of faith and its enormous impact on European culture, science, religion and geopolitics over hundreds of years.

The Victorian era throbbed with imagination, as is evident from its novels, narrative poetry and paintings. Truro Cathedral stands as a testimony to the energy and ambition of the age, and is a compelling example of storytelling set in stone and glass.

Above : Fishermen at Newlyn, and Dolcoath Mine – one of the largest, deepest and most productive mines producing copper and, later, tin in Cornwall. These 1907 windows are making a point, celebrating Cornwall’s traditional industries at a time of economic decline.

BIRMINGHAM CATHEDRAL – Last Judgement Window (1897)

Stained-glass window (one of four), designed by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) and made in the workshop of Morris & Co., west end, 2.64 × 1.3 m

The Last Judgement is perhaps the masterpiece of Edward Burne-Jones and Morris & Co.’s work in stained glass (William Morris died before the window was finished). Situated at the west end of the Cathedral, this monumental window draws the worshipper into the drama of the Last Judgement with its expressionist quality of movement, the total fluency of its glazing, and the striking density of its colours (it features more ruby glass than any other window from before 1945).

Split into three parts, the drama begins with Christ enthroned in glory and surrounded by a circle of angels, with the Archangel Michael blowing a trumpet. Below this section is a dark and ruined cityscape with both Renaissance and contemporary features that amounts to a challenge from the socialist artists for the city to live up to higher standards. The bottom of the window shows a crowd of people – young and old, rich and poor – standing on tombs as they await the Judgement. The window was extensively restored by Holy Well Glass in 2024, and it is a delight to be able to see its details with a new clarity.

The window, and Burne-Jones’s artistic vision, exhorts the viewer to attend to the Last Judgement parables of Jesus, particularly the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew 25. A major part of the Cathedral’s life is a regular breakfast under the window for those who are homeless or hungry. There is something beautiful and poignant in the juxtaposition of an outstanding artwork with toasted sandwiches, tea and conversation on these mornings, and in how the window and the stories behind it shape the Cathedral’s corporate life. The window is a constant reminder to look for the face of Christ in the faces of one’s neighbours.

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL – Lady Chapel Windows (1899–1910)

Designed by Christopher Whall (1849–1924) in conjunction with his daughter Veronica Whall (1887–1967) and made in Whall’s workshop, Central South Window, 9.75 × 3 m

At the east end of Gloucester Cathedral, beyond the Great East Window, lies the 1480s Lady Chapel. In 1897/8 the Dean and Chapter took the courageous decision to commission a relatively unknown and distinctly modern designer, Christopher Whall, to design new glass for the Lady Chapel.

Whall was part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which placed a strong emphasis on beauty and on a return to artisanal skill. The work produced by Whall and his workshop collaborators is characterised by vibrant colours, the use of textured slab glass, and a close attention to detail. There is a thematic unity in both the telling of the story of Mary in the horizontal panels and the ordering of subjects in the windows from top to bottom.

Of particular note is the arrangement of the British saints in the lower lights. Saints from the North are on the north side of the Lady Chapel and those from the South are on the south side. Whall respected and made the most of the remaining medieval glass that was available in the windows. The best examples of Whall’s resourcefulness in this regard are the shaft of starlight shining down on the Nativity and – a favourite with children who manage to find him – a farting grotesque.

There is a touching poignancy in the portraits of St Cecilia and St Christopher above the chantry chapels. The two saints face one another and were respectively designed by Whall and his daughter Veronica, with each artist using the other as a model. Veronica inherited her father’s business on his death in 1924 and continued to run the studio until 1953.

CHELMSFORD CATHEDRAL – Holderness Window (1905)

Designed by Henry Holiday (1839–1927) and made at Lowndes & Dury, south aisle, immediately west of the south port entrance, 4.6 × 2.5 m

The Holderness Window was designed by Henry Holiday, an artist who (as is evident from the window itself) was profoundly influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – a number of whose members he counted as friends. Holiday succeeded Edward Burne-Jones as principal designer at Powell’s Glass Works in 1861, but by the time the Holderness Window was designed his involvement with the Arts and Crafts Movement had led him to set up his own glass works in Hampstead.

The window commemorates Caroline Maude, the wife of Lt Hardwicke Holderness. Above, below and upon its triptych of images, quotations from Scripture help us to interpret its iconography. The arrangement is held together by an overarching scriptural sentence on the nature of marriage: ‘For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother and shall be joined unto his wife and they two shall be one flesh’ (Matthew 19:5–6).

The figure in the left-hand panel walks a pilgrim road, and the words above and below him read ‘we walk by faith’ (2 Corinthians 5:7) and ‘thou wilt shew me the path of life’ (Psalm 16:11). In the right-hand panel dark water surrounds a woman’s figure; submerged as she is, she is held by red- winged angels, and below her, words from Psalm 130 speak of death and loss: ‘out of the depths have I cried unto thee’. The same woman’s figure appears in the central panel, surrounded by spirals of mist and lifted up by the same red-winged angels. The verse below her reads: ‘this mortal must put on immortality’ (1 Corinthians 15:53).

Together the three panels speak powerfully of faith and love in the face of loss, and of a married intimacy, made in Christian hope, that transcends even death.

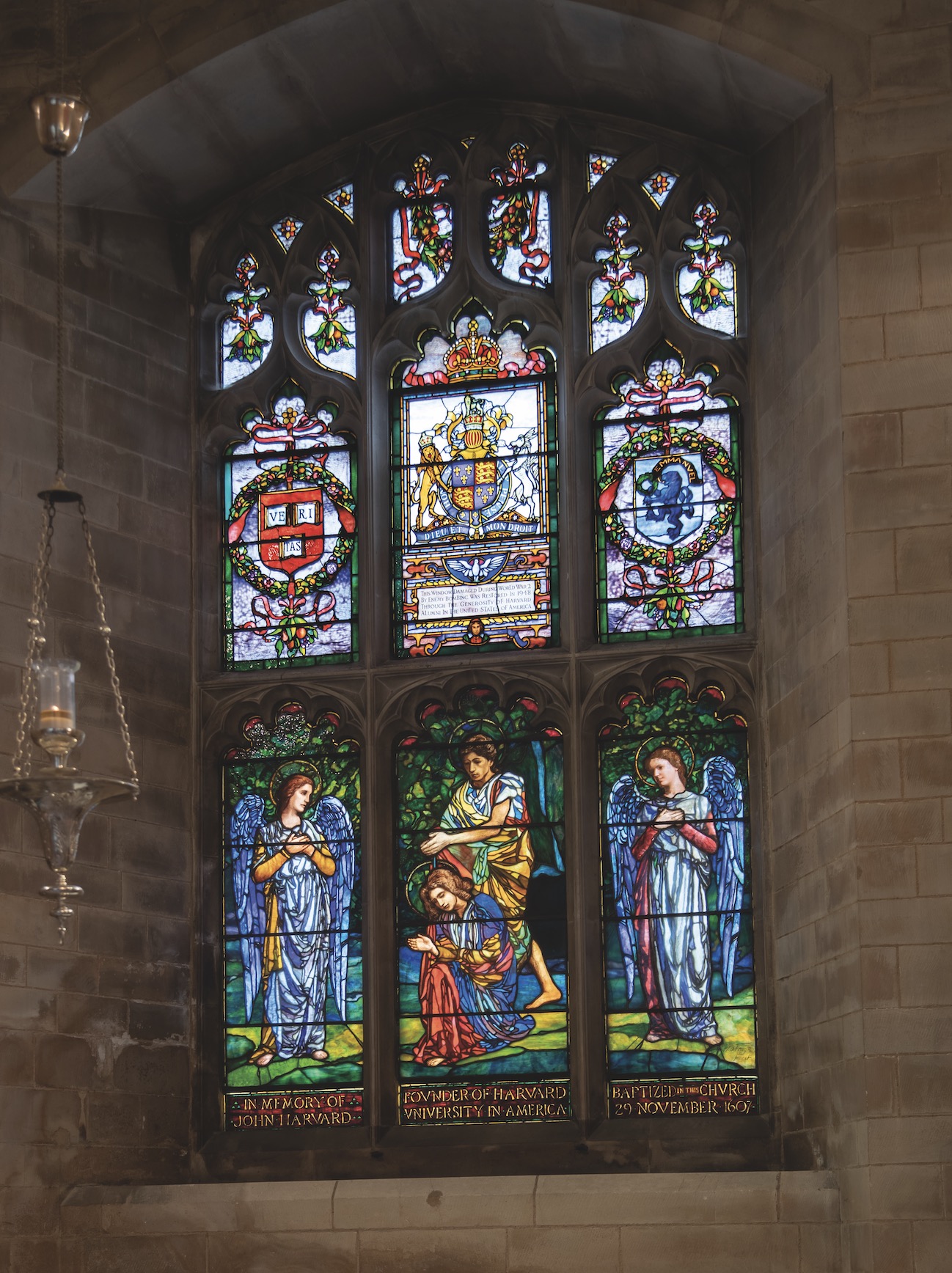

SOUTHWARK CATHEDRAL – Harvard Chapel Window (1905)

Opalescent window by American artist John La Farge (1835–1910) depicting the Baptism of Christ, north transept, 3.7 × 2.1 m

The ancient Parish Church of St Saviour became Southwark Cathedral in 1905 when the new diocese of Southwark was formed in response to the massive increase in the population of South London. The Cathedral precinct is restricted in size and is dwarfed by the twenty- first-century urban development of Bankside.

The Cathedral has a unique location in the heart of historic Southwark, by the southern approaches to London Bridge – for centuries the only southern access to the City. The Cathedral windows are largely from the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Many provide a colourful testament to the Cathedral’s long association with talented writers, poets and preachers, as well as with royalty.

The windows in the north aisle – all created by the C.E. Kempe studios between 1900 and 1920 – illustrate the lives of Oliver Goldsmith, Samuel Johnson, Henry Sacheverell, John Bunyan, Alexander Cruden and John Gower. The latter was a friend of Geoffrey Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales, whose window completes the series. Beneath a ‘tabard’ representing the Tabard Inn in Borough High Street, we see the pilgrims streaming out on horseback towards Canterbury.

The only stained glass in the south aisle is Christopher Webb’s fine memorial to William Shakespeare. The Kempe windows in the south aisle were blown out during an air raid in 1941 – in some ways a blessing, as clear light now floods the building’s interior.

In 1905 an opalescent window (unique in the UK) by the American glass designer John La Farge was commissioned for the Cathedral’s Harvard Chapel by Joseph Choate, the US Ambassador. The ‘Baptism of Christ’ window commemorates John Harvard, from whom Harvard University takes its name, who was born in Southwark and baptised in St Saviour’s Church in 1607. John Harvard emigrated to Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1637.

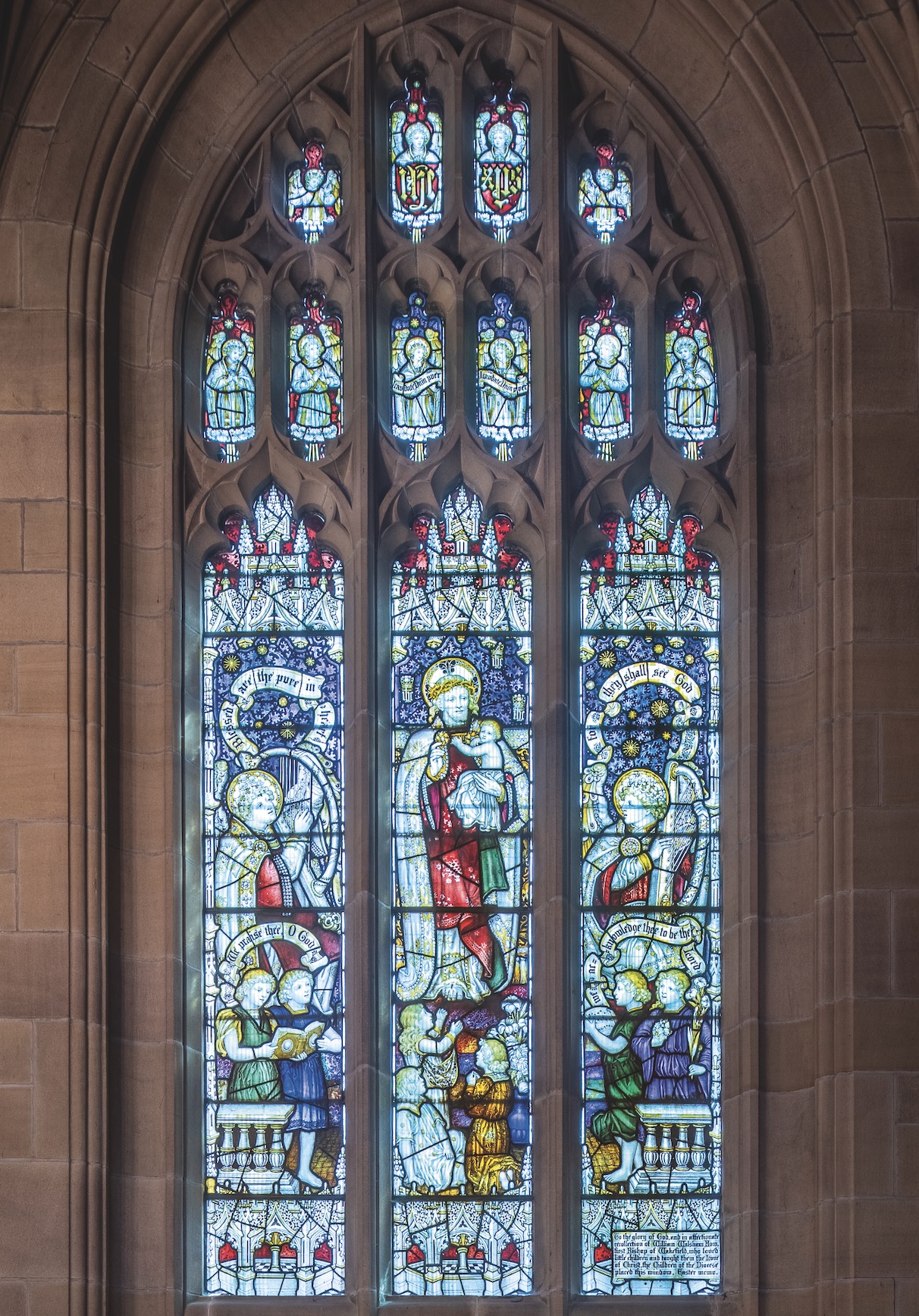

WAKEFIELD CATHEDRAL – Children’s Window (1905)

Part of larger scheme of twenty-five windows by C.E. Kempe (1837–1907), produced by his company C.E. Kempe & Co. in London, east end of the south quire aisle, 3.6 × 1.6 m

The Cathedral Church of All Saints Wakefield houses an exceptional collection of Victorian and Edwardian stained-glass windows. Twenty-five of these were designed and made by Charles Eamer Kempe, who established his stained-glass window company C.E. Kempe & Co. – which at its height employed up to fifty people – in London in 1868. The Wakefield Cathedral windows span a period of just over thirty-five years, the earliest having been installed in 1872 and the last in 1907.

The Children’s Window, which was made in 1905, is situated at the east end of the south quire aisle. It is dedicated to the memory of William Walsham How, the first Bishop of the Diocese of Wakefield. Walsham How was commonly known as ‘the children’s bishop’ due to the work he had done in London’s East End while serving as Bishop of Bedford. He was also a favourite bishop of Queen Victoria’s.

The Children’s Window was commissioned on behalf of the children in the Wakefield diocese after Walsham How’s sudden death on 10 August 1897, which took place while he was on holiday in Ireland.

The central panel of the window depicts Jesus carrying a child. Typically for Kempe’s work, it takes inspiration from fifteenth-century glass, uses deep colours that contrast with white glass (the latter of which Kempe often decorated with silver stain), and features delicately painted details on patterned backgrounds. In the left-hand panel towards the bottom of the window there is an image of a golden wheatsheaf; this was Kempe’s trademark from 1895 to 1907.

ROCHESTER CATHEDRAL – Annunciation Window (c.1910–18)

First of five six-light Perpendicular windows, attributed to Burlison & Grylls, in Lady Chapel (on south-west of the Cathedral), 2.8 × 1.6 m

Rochester is the second-oldest see in England. Its Lady Chapel on the south-west was completed in the early sixteenth century – a final major rebuild before the dissolution of the monasteries. A tall Perpendicular space was created with five magnificent six-light Perpendicular window arches. No medieval glass now remains, but the Lady Chapel windows have been filled with early twentieth-century stained glass attributed to the firm of Burlison & Grylls. The three South Windows tell Jesus’s early story through his mother’s eyes.

The first window, which is dedicated to Archdeacon John Tetley Rowe (d. 1915), depicts the Annunciation as described in the Gospel of Luke (1:26–38): we see the Angel Gabriel appearing to the Blessed Virgin Mary to announce that she will conceive and give birth to Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Mary is depicted on the right side of the window, dressed in a deep-blue robe symbolising humility and heavenly grace. Her face is serene yet touched with awe, reflecting her humble acceptance of her divine role. On the left, Gabriel stands gesturing towards Mary with both reverence and authority, embodying the solemnity of his message.

The Holy Spirit – represented as a luminous white dove – descends from above the depicted scene via golden rays of light. These rays stream down towards Mary, signifying the intervention of the Holy Spirit through which the conception of Jesus takes place.

The composition uses strong blue, red, green and yellow glass, most pronounced in the robes and haloes of the figures. These are set against a background of clear glass with a hint of green, and diamond-shaped leading. The whole is filled with delicate yet vibrant, partially symbolic floral and leaf patterns, bringing an ethereal light into the chapel.

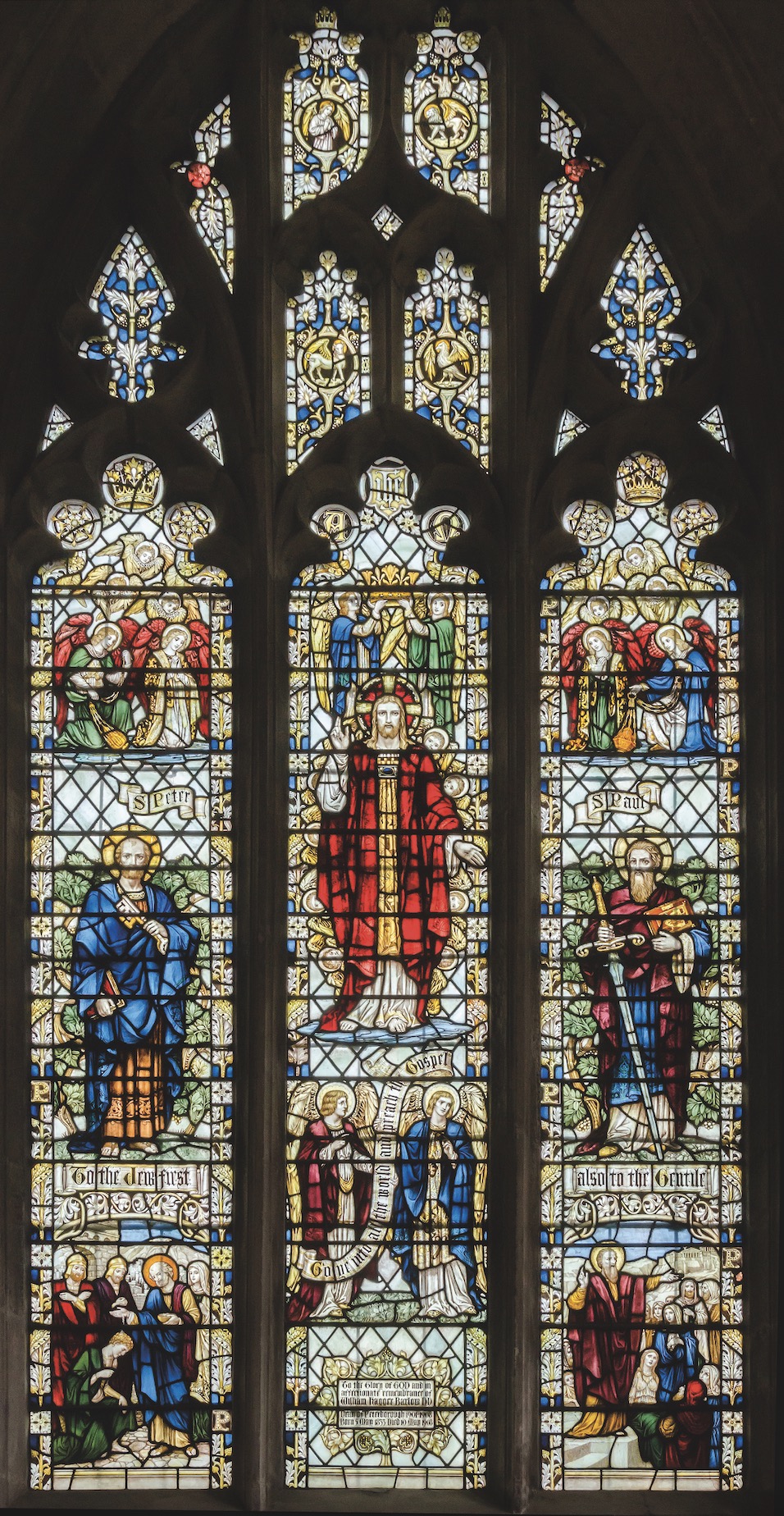

PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL – Dean Barlow Memorial Window (1914)

The seventeenth-century antiquary Symon Gunton recorded that the windows in Peterborough Cathedral were ‘very fair, and [that] the Cloister Windows were most famed of all, for their great Art and pleasing variety’. Unfortunately, the iconoclasm of the English Civil War laid waste to most of the Cathedral’s medieval glass; the only surviving fragments of that great collection can now be seen high up in the eastern apse of the building.

Peterborough Cathedral has a small collection of post-medieval stained glass. The majority of the windows are memorial windows; these include works by Clayton & Bell; Heaton, Butler & Bayne; Burlison & Grylls; Lavers, Barraud & Westlake; and others – not forgetting a fine window designed by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, made in the celebrated studio of William Morris & Co. in 1862.

One of the most pleasing works of stained glass in the Cathedral is the William Hagger Barlow Memorial Window, which is located on the north side of the New Building. Manufactured in 1914 by James Powell & Sons of Whitefriars, the window still contains elements of a late Pre-Raphaelite style, though the design transitions into the idiom of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Observers particularly appreciate the well-balanced colour scheme of the light and lofty three-light= window. Beneath St Peter and St Paul in the two side lights are scenes of their missionary work. The centre light contains Christ in Majesty, surrounded and crowned by angels and cherubim. Such details draw the pilgrim closer, prompting them to explore the underlying biblical narratives and to appreciate the superb craftsmanship of this very fine window.

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Picture credits – York Glaziers Trust © Chapter of York; David Brook; Andy Marshall; Mel Howse and Vitreous Art Ltd; Portsmouth Cathedral; Marcus Green; Lichfield Cathedral; The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral; Dan Beal; Lynne Alcott Kogel; Wells Cathedral; Holy Well Glass; Kevin Lewis; Tom Soper Photography; Rob Scott; Dean and Chapter of Christ Church, Oxford; Gordon Plumb; Winchester Cathedral; Janet Gough; Kevin Caldwell © Off the Rails Australasia Pty Ltd; Steven Jugg; Declan Spreadbury/Salisbury Cathedral; Gordon Taylor; Bradford Cathedral/Philip Lickley; Chris Parkinson; Gill Poole; Chris Hutt; Paul Barker; Christopher Guy/Worcester Cathedral; Mark Charter; © David Whyman; Clive Tanner; Peterborough Cathedral; Bill Smith/Norwich Cathedral; Peter Hildebrand/Visit Stained Glass; Luke Watson; Patrick Fitzsimons; Bristol Cathedral; David Pratt; Aaron Law; Manchester Cathedral/Nathan Whittaker; Liverpool Cathedral; Gareth Jones Photography; Salisbury Cathedral; St Albans Cathedral; Dr Chris Brooke; Southwell Cathedral Chapter; Blackburn Cathedral; Richard Jarvis and Aidan McRae Thomson of Norgrove Studios Ltd.