Divine Light – The Stained Glass of England’s Cathedrals

Stained-glass windows combine light and colour with imagery and sophisticated design to illuminate interior spaces, communicate religious and other messages, and perhaps offer us a glimpse of heaven.

Pt 1 – The Middle Ages & Reformation Pt 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century Pt 3 – Modern Age

Visitors are often captivated by the stained glass of England’s cathedrals, but few realise that it represents a significant national art collection. For example, the City of Birmingham’s most internationally renowned artworks are arguably the four windows – the Nativity, Ascension, Crucifixion and Last Judgement.

Designed by Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris in the late nineteenth century for St Philip’s, now Birmingham Cathedral, where they can be viewed daily. Perhaps because they are built into cathedral walls, stained-glass windows rarely appear in exhibitions. But they are frequently visited and admired in situ, as cathedrals have always been public spaces, attracting worshippers, pilgrims, individuals seeking sanctuary, tourists, and, critically, donors.

Glass is formed from a mixture of silica (sand), minerals and binders such as sodium carbonate. Coloured or stained glass is produced when these are combined with metallic oxides or salts at very high temperatures. Stained glass was initially invented and developed in the Middle East. The Romans later introduced glass blowing, which enabled them to create glass jewellery, decorations and drinking vessels. In early Christian times, small glass pieces began to be incorporated into windows. St Benet Biscop introduced coloured-glass windows from Rome and his monastic church St Paul’s Jarrow, home to the Venerable Bede, contains excavated fragments of England’s oldest-known window glass (dating from the seventh century). The earliest notable surviving stained-glass schemes are at Canterbury and were created following Archbishop Thomas Becket’s murder in the Cathedral in 1170. It has recently been established that Canterbury’s Ancestors stained-glass panels may have been made even earlier, 1130–60 (prophet Methuselah). England’s cathedrals can therefore boast stained-glass treasures and stained-glass production for nearly 900 years.

Filling large architectural window openings with stained glass requires the combined skills of glassmakers, masons and artisans. Artists’ designs must accommodate often complex window and tracery shapes. Designs and storyboards must meet the approval of the donors and clergy who coordinate the work, as well as that of the communities for which these windows are intended. Immense artistic and technical skills are required to then create scenes in coloured glass, vitreous paint and lead (often working from large-scale cartoons).

Abbé Suger (1085–1151) argued that light as it entered a church through stained glass became divine light, symbolising God’s presence on Earth. He went on to build the abbey and royal church of Saint-Denis, north of Paris, which was designed to be a ‘temple of light’. His Cathedral made innovative use of ribbed vaults, pointed arches and large stained-glass windows. Saint-Denis marks the transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture.

English stained glass and the desire to fill cathedral buildings with divine light are closely associated with the evolution of Gothic architecture – the first architecture breaking entirely new ground since Roman times. Gothic windows became taller and thinner over time – see for example the Five Sisters grisaille lancet windows at York (above). Lancets were soon merged and divided by straight and curving stone tracery, and also came to occupy more of the wall space, as we can see at Gloucester Cathedral. Simultaneously, the glass designs filling these windows reflected developing styles in ecclesiastical art.

Even today, amidst the abundance of TV and video, the light passing through Wells Cathedral’s exquisite Jesse Window (above), with its curling vines and its S-shaped Virgin placed beneath Christ crucified on a swaying tree, creates a stunning display, spilling onto the adjacent stonework. Despite our limited knowledge of the medieval religious world, attending evensong at Wells Cathedral is an otherworldly experience.

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

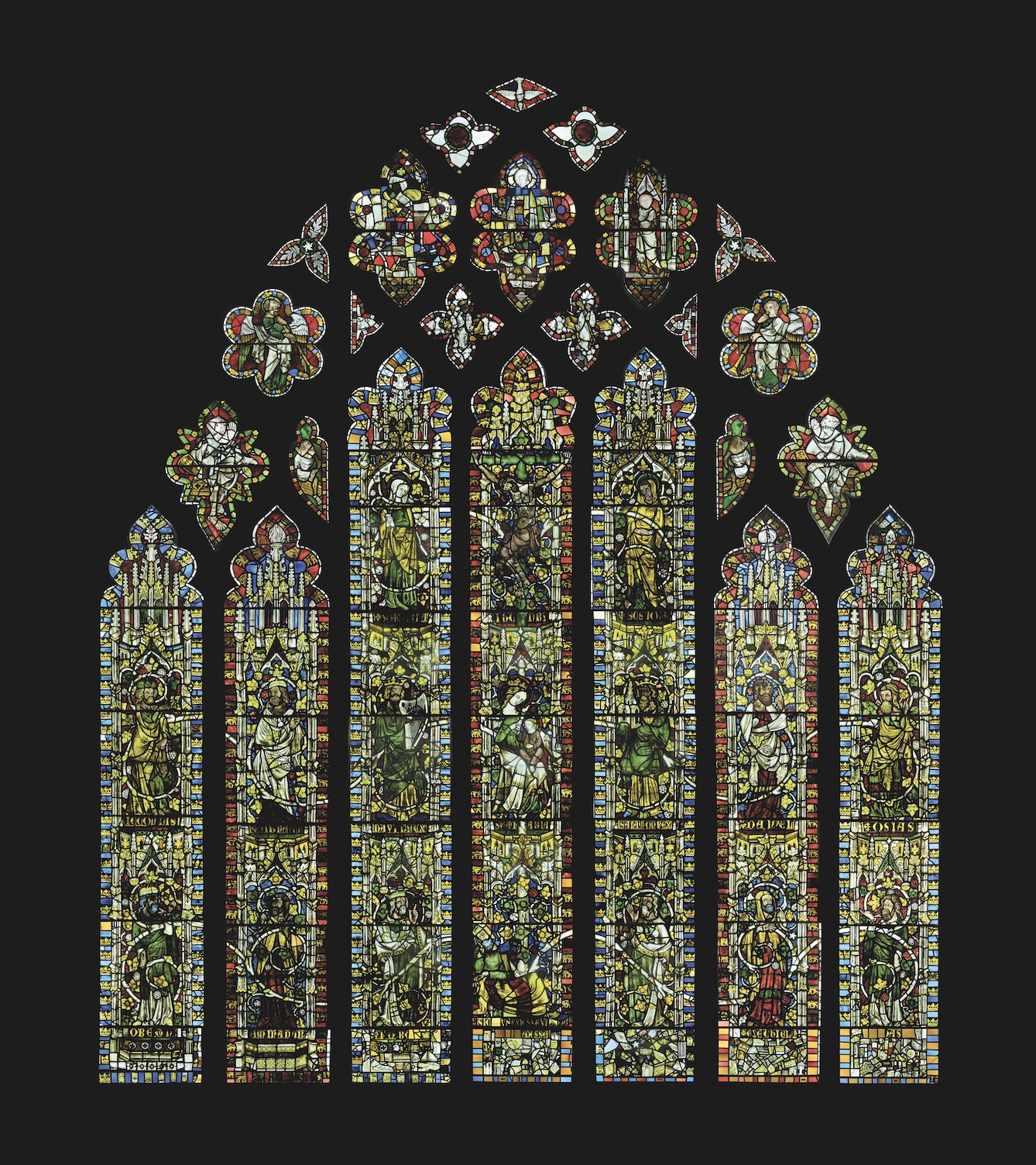

Glass is inevitably vulnerable to forces such as weather, wars and iconoclasm, as well as to periods of straightforward indifference, but it is nonetheless remarkable how much medieval stained glass has survived. Few medieval windows remain untouched today, however, and sometimes only fragments remain from vast windows (Winchester Cathedral provides a striking example). The glass of the West Window at St George’s Chapel, Windsor was removed and stored during the English Civil War (1642–51). It underwent restoration in the 1760s and then again in the 1840s, when seven new figures were introduced by Thomas Willement. Several of these figures are composites of glass from different periods. Similarly, the lower panes of Carlisle’s East Window (below)) – the glass in the upper part of which dates back to the mid-fourteenth century – were created by Hardman & Co. in the 1860s.

After the disruptions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – partly Reformation- and Renaissance-driven – and the consequent loss of ancient glassmaking techniques, the nineteenth century saw a revived interest in medieval stained glass. This period once again valued stained glass for purposes of devotion, teaching and decoration. The mid- and late nineteenth century was a golden age of stained glass production, with many windows being created as memorials. Reacting against the industrialisation of glassmaking, some artists, like the pre-Raphaelites who formed William Morris & Co., explored radical new techniques and approaches (early examples at Bradford Cathedral, and then later at Birmingham). Arts and Crafts practitioners such as the influential Christopher Whall (Gloucester Lady Chapel) sought to return to closer working with glassmakers and experimented with new handmade glass techniques.

At this time women glass designers came to the fore. Mary Lowndes (1857–1929), formerly an assistant to Henry Holiday (Chelmsford), co-founded the Glass House studio in Fulham in 1906, which nearly fifty years later Moira Forsyth used to create her Rose Window for Guildford Cathedral.

Perhaps surprisingly considering the democratic worship style of the twentieth century, stained glass remained popular. Arguably England’s most coherent and impressive stained-glass cathedral is Coventry, where in the 1950s architect Basil Spence worked with John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens on the huge abstract Baptistery Window. In addition to commissioning art and furnishings for Coventry Cathedral, Spence worked with Lawrence Lee and his students from the Royal College of Art – many of whom went on to become famous glassmakers – on a major scheme of windows that, unusually, was designed to be read from the east. At Coventry we also find new techniques, as with Margaret Traherne’s use of dalle- de-verre glass in the Chapel of Unity. At Manchester Cathedral, Antony Hollaway’s West Windows, installed between 1972 and 1995, inject an array of colours into the Perpendicular church and take on traditional biblical themes in a distinctively modern abstract style.

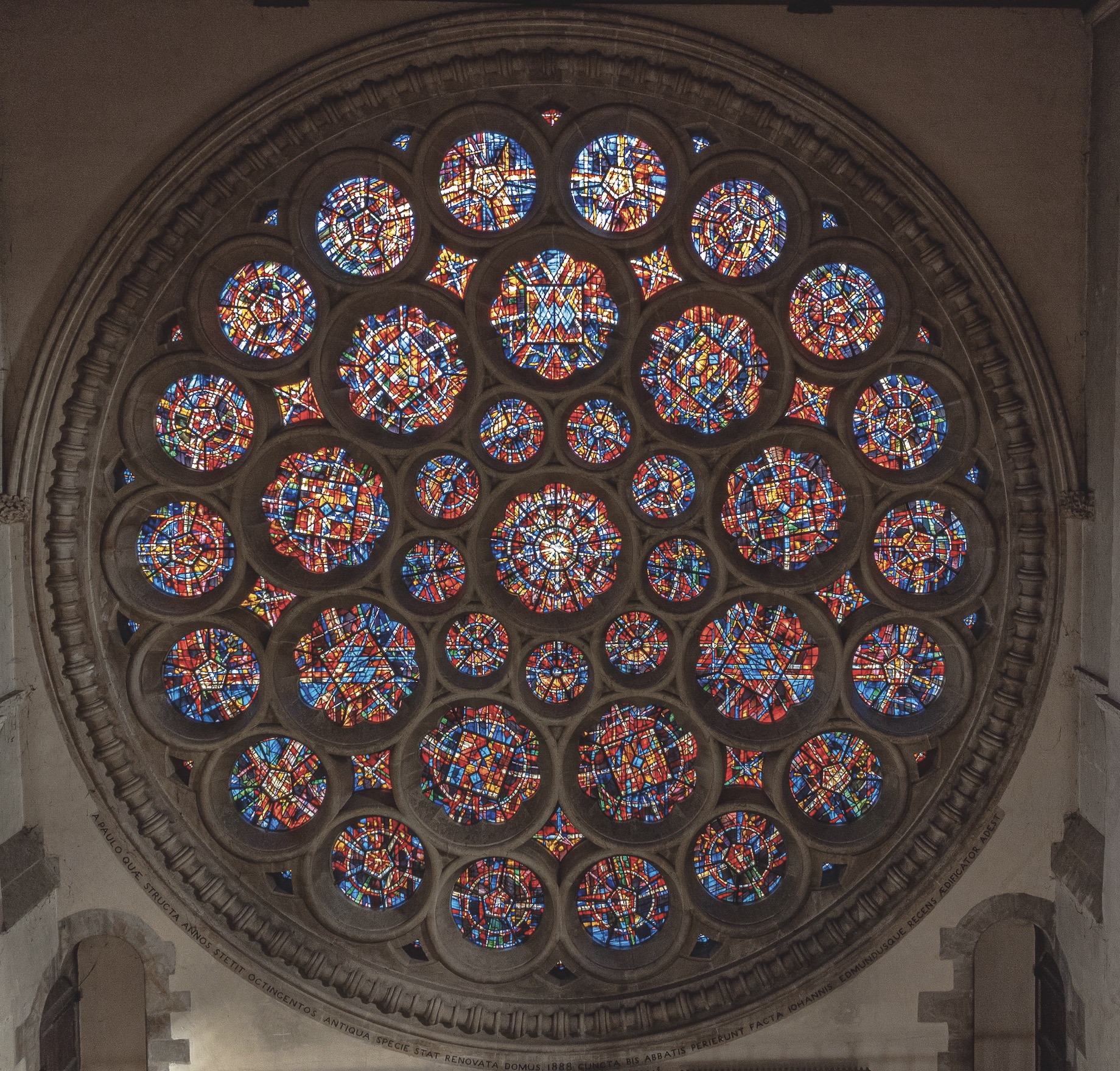

It is inspiring to see thought-provoking new glass being commissioned in the present day. Such commissions include abstract glass for ancient cathedrals – see for example the powerful Rose Window by Alan Younger that immediately greets visitors to St Albans Cathedral, or Mel Howse’s transformative Illumination Window at Durham. Thomas Denny’s creations at Leicester Cathedral – the Richard III Redemption Windows (2016) – meanwhile seek to engage with viewers on a more reflective and personal level.

Caring for England’s cathedral glass collection is crucial. There have been many excellent conservation projects in recent years; for example, Barley Studio conserved Lichfield’s sixteenth-century Herkenrode windows and installed an external layer of protective isothermal glass (p. 32), and Holy Well Glass cleaned and conserved Exeter’s sixteenth-century windows. But in 2023, stained glass was added to the Heritage Crafts Red List of Endangered Crafts due to a halt in mouth-blown sheet glass production in England, the limited number of workshops offering specialist training, and the decline in higher institutions providing technical and art-historical training in stained glass. Added to this are the complicated systems for commissioning and approving new glass schemes for churches and cathedrals. Jack Clare of Holy Well Glass believes this has resulted in a ‘massive gap in designing new work to scale’.

For this book we follow fifty windows or glazing schemes chosen by each of the cathedrals of the Church of England, as well as from two Royal Peculiars (Westminster Abbey and St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle) and St German’s Cathedral, Isle of Man. Together they exhibit remarkable craftsmanship and stories from every century from the twelfth century onwards. Although there are highly significant artists – including outstanding modern practitioners such as Keith New (1925–2012), John Maine (b. 1942) and Mark Cazalet (b. 1964) – who could not be included in this volume for reasons of space, the entries collected here indicate the depth and range of stained-glass artistry in our cathedrals.

England’s remarkable cathedral glass collection is accessible nationwide and open year-round. We encourage people to go and seek out cathedral glass for themselves, and to enjoy engaging with it as our predecessors did in previous centuries.

Janet Gough, April 2025

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Picture credits – York Glaziers Trust © Chapter of York; David Brook; Andy Marshall; Mel Howse and Vitreous Art Ltd; Portsmouth Cathedral; Marcus Green; Lichfield Cathedral; The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral; Dan Beal; Lynne Alcott Kogel; Wells Cathedral; Holy Well Glass; Kevin Lewis; Tom Soper Photography; Rob Scott; Dean and Chapter of Christ Church, Oxford; Gordon Plumb; Winchester Cathedral; Janet Gough; Kevin Caldwell © Off the Rails Australasia Pty Ltd; Steven Jugg; Declan Spreadbury/Salisbury Cathedral; Gordon Taylor; Bradford Cathedral/Philip Lickley; Chris Parkinson; Gill Poole; Chris Hutt; Paul Barker; Christopher Guy/Worcester Cathedral; Mark Charter; © David Whyman; Clive Tanner; Peterborough Cathedral; Bill Smith/Norwich Cathedral; Peter Hildebrand/Visit Stained Glass; Luke Watson; Sheffield Cathedral; Patrick Fitzsimons; Bristol Cathedral; David Pratt; Aaron Law; Manchester Cathedral/Nathan Whittaker; Liverpool Cathedral; Gareth Jones Photography; Salisbury Cathedral; St Albans Cathedral; Dr Chris Brooke; Southwell Cathedral Chapter; Blackburn Cathedral; Richard Jarvis and Aidan McRae Thomson of Norgrove Studios Ltd.