Divine Light – The Stained Glass of England’s Cathedrals – Middle Ages and Reformation

Canterbury Cathedral’s Miracle and Bible Windows were created in the wake of Archbishop Thomas Becket’s murder inside the Cathedral in 1170 – an event that sent shock waves across Europe. The windows together form England’s oldest comprehensive stained-glass scheme. As sophisticated as anything produced in France during the same period, these round-headed Romanesque windows are brimming with discrete scenes set in lead-divided panels. They were produced using deeply coloured pot-metal glass sourced from continental Europe, with details added in vitrifiable paint.

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Medieval glass rendered saints and biblical subjects in exquisite detail (see for example the Jesse Window of Wells Cathedral. It also developed in tandem with Gothic architecture and with stylistic changes taking place across the other ecclesiastical arts.

Windows became taller and thinner from c.1200 onwards, and over time stone window traceries became more complex (Carlisle provides an outstanding Decorated example. The grand rose window (as at Lincoln) was also a popular form. Grisaille glass – clear glass flashed with grey tones and light colour, and painted with foliate patterns or emblems – is exemplified by the prominent Five Sisters Window in York Minster.

The final flourish of the Middle Ages was the production from the mid-fourteenth century onwards of vast Perpendicular windows – wide as well as tall – in Gloucester, York and St George’s Chapel, Windsor.

The Protestant Reformation led to the destruction of some images deemed to be superstitious – the personification of the three persons of the Trinity, for example – as well as to later hesitations over what could be included in window design (see the 1630s Old Testament scene at Oxford). Winchester’s Great West Window is now filled with fragments of broken medieval glass that were reassembled in the late seventeenth century.

Christopher Wren made superlative use of clear glass to light St Paul’s, the first Protestant-built cathedral. Biblical figures and narratives slowly returned to cathedral windows, sometimes painted on clear glass in enamel paints (partly because continental pot-metal coloured glass was difficult to source). This was done in a more painterly manner than medieval glasswork, often using larger pieces of glass (reducing the amount of lead required), and with scenes that spread across consecutive lights. A fine example of this kind painted glass survives in the Moses Window at Salisbury.

CANTERBURY CATHEDRAL – The Sower Among Thorns and on Good Ground, Second Bible Window (c.1180)

Stained-glass panel from one of two (originally twelve) Bible Windows, north choir aisle, 0.66 × 0.7 m

Part of a now largely lost cycle of twelve windows illustrating Old and New Testament subjects, this panel is one of a pair devoted to the Parable of the Sower (Matthew 13:1–23).

The Sower is embedded in his surroundings; he is painted with elongated limbs in an elegant pose as he casts seed onto fertile ground. Some falls among thorn bushes and appears to be lost. He looks back – perhaps to the past – but strides confidently forward into a future when the field under his feet will bear the fruits of his labours. His basket is woven in a herringbone pattern and attached to a long strip of cloth that is slung over his neck. The artist’s attention to detail is such that even the small feet protruding from the bottom of the basket are depicted. At the edge of the field, in a great clump of swirling folds, is the man’s cast-off cloak.

The Sower’s rich clothing – with high boots, hose, an undertunic and an overtunic decorated at the neck – highlights his importance.

The figure is set into an impressive landscape which – unusually for a medieval work of such an early date – covers the entire available space. The Sower is shown striding along a freshly ploughed field that has the characteristic ridge-and-furrow appearance associated with medieval ploughing techniques. The diagonal arrangement of the straight lines of the furrows is juxtaposed with curved hills and animated clumps of vegetation. This creates a sense of drama, space and distance that departs from the usual medieval approach of depicting landscape with just a few token elements. Here in Canterbury, the artist treats the landscape as a subject of equal importance to the central figure of the story.

YORK MINSTER – Five Sisters Window (c.1250)

Five Early English lancet windows, filled with more than 100,000 pieces of grisaille glass, north wall of north transept, each window 16.2 × 1.5 m, total area 121 m2

In the years c.1225–50 Archbishop Walter de Grey rebuilt the transepts and crossing of York Minster, creating a new and well-lit space in the latest architectural style. In 1226 de Grey secured the official canonisation of his twelfth-century predecessor William Fitzherbert, and it was in the new transepts that pilgrims to St William’s shrine could assemble in eager expectation.

Entering from the city under the striking new Rose Window in the south transept, they would have been amazed by the unprecedented quantity of glass ahead of them in the north transept. In a world in which the average person had little, if any, glass in the windows of their home, the sparkling cliff-like majesty of these five lancets would have invited comparison with the heavenly Jerusalem of the Bible, ‘with walls like unto clear glass’ (Revelations 21:18).

The window was deliberately light and bright in its decoration, with elegant painted foliage decoration interspersed with small amounts of colour. The intricate geometry of the window’s patterning, with a different design being applied for each light, made great demands on the technical skills of the anonymous glaziers. It was the window and not its makers that ultimately made a name for itself, and from the eighteenth century it became known as the Five Sisters. Its fame spread, thanks in no small measure to the popularity of Charles Dickens’s novel The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, in which was recounted the romantic but entirely spurious tale of five maiden sisters whose embroidery was the basis for the stained-glass design. The story was first published in March 1838, shortly after Dickens’s own visit to Yorkshire. Despite damage and deterioration over time, the window continues to inspire the Minster’s visitors.

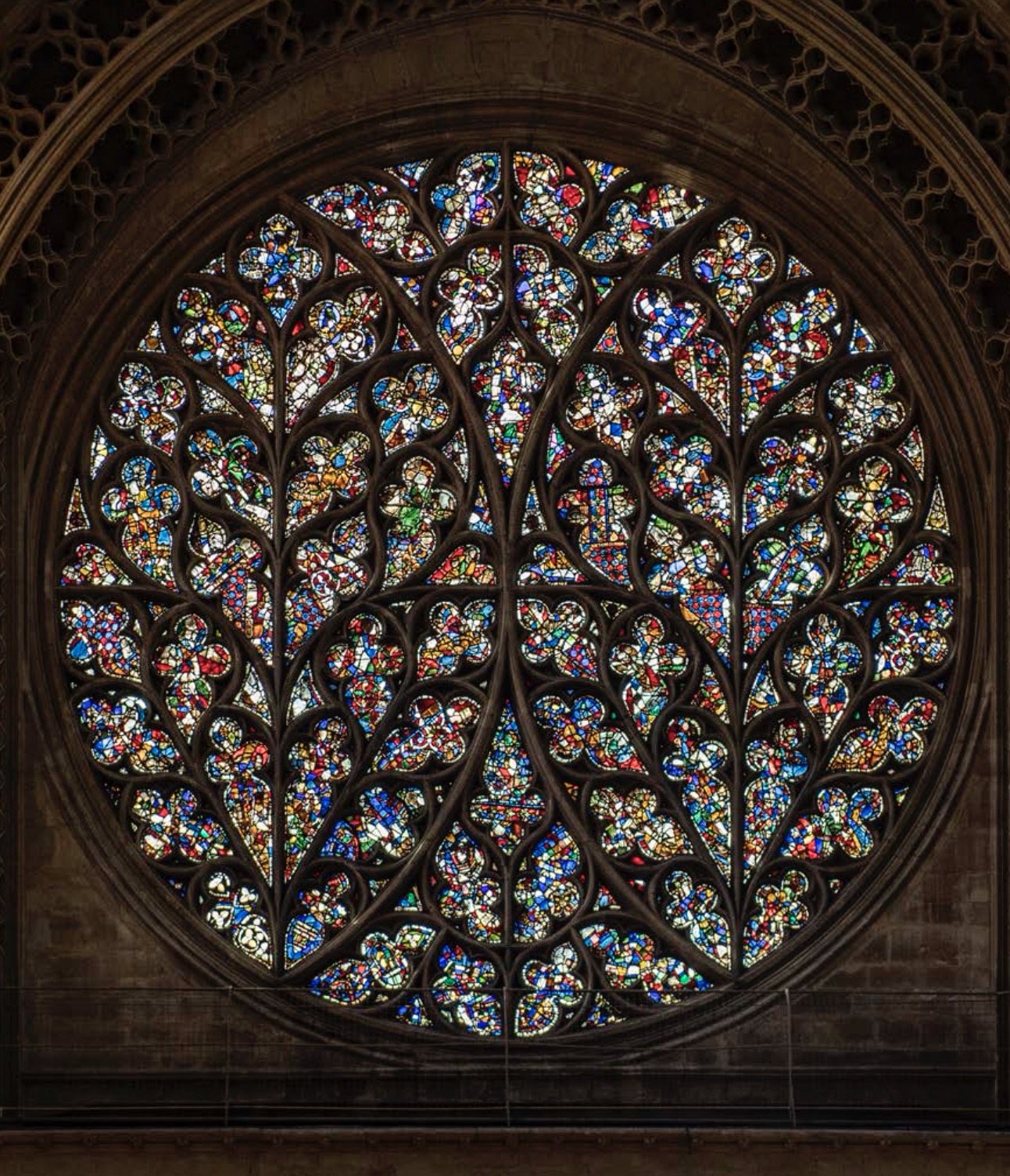

LINCOLN CATHEDRAL – Bishop’s Eye Rose Window (c.1330s)

Reconstructed as two curvilinear leaves, originally depicting the Last Judgement, later more fragmentary, overlooking the south-west transept, diameter nearly 8 m

Overlooking the south-west transept of Lincoln Cathedral, the kaleidoscopic ‘Bishop’s Eye’ window is as imposing as it is enchanting. Alongside the better-known ‘Dean’s Eye’ window to the north, the Bishop’s Eye is a rare extant example of a medieval English rose window. With its singular design and a diameter of almost 8 metres, it forms a significant part of the Cathedral’s medieval glazing heritage.

Like many historic windows, Lincoln’s South Rose has undergone various alterations and amendments over the centuries. The original Early English Gothic window, dating from the beginning of the thirteenth century, failed catastrophically and had to be rebuilt just a century later. The window we see today therefore dates from the first half of the fourteenth century. Its delicate Curvilinear tracery creates a semblance of two immense veined leaves, and this organic theme is enhanced by the fragmentary glass contained within.

The window’s colourful patchwork of glass exists more by necessity than by design, however. Much of the medieval glass was damaged or destroyed during the upheaval of the English Reformation and the Civil War, and the window was left in a dilapidated state for over a century. A general reordering of the Cathedral’s stained-glass collection was carried out during the latter half of the eighteenth century, and the huge Rose Window was reglazed in its current form. Today it contains an amalgamation of medieval glass assembled from various windows from around the Cathedral, but enough surviving fragments of the fourteenth-century glazing scheme remain in situ to suggest a representation of the Last Judgement – a subject which would have mirrored, and amplified, the iconographic programme of Lincoln’s North Rose Window.

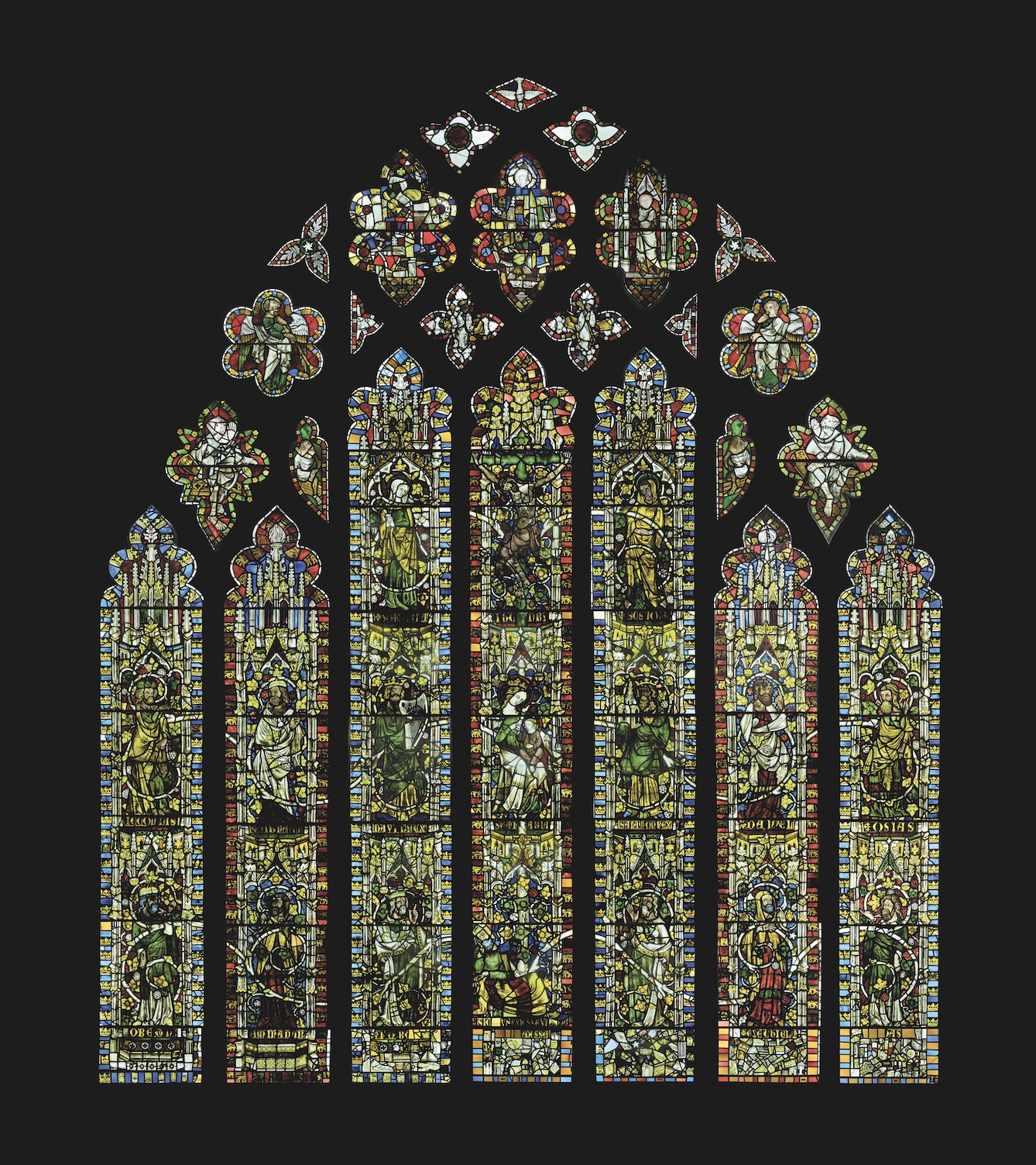

WELLS CATHEDRAL – Jesse Window (c.1340)

Seven lights with twenty-seven panels in lustrous symmetrical Curvilinear scheme, high gable at east end of quire, c.7.5 × 6.5 m

Wells has an amazingly varied collection of glass, from windows made up of fragments in the Lady Chapel, to small detailed medieval traceries in the quire aisles, to tiny windows using silver stain, to dramatically coloured glass from Rouen and a magnificent Edwardian River of Water of Life. High up at the east end of the quire shines one of the Cathedral’s greatest treasures: the Jesse Window.

It is part of a seven-window scheme that forms a beautiful reredos above and around the high altar. It dates from c.1340 and is approximately 90 per cent original medieval glass. The artists are unknown, but it is clear from the window’s internal stylistic variations that three were involved. The window represents Christ’s authority as it derives from his descent from Abraham – it shows family, prophets and kings. Jesse himself lies asleep at the base of the central light with a rod rising from his person, as Isaiah prophesied (Isaiah 11:1), as well as a white vine that winds itself round all the other figures. Above Jesse is the Virgin Mary with the Infant Christ in her arms. A green cross emerges from behind her throne, upon which Christ is seen crucified. In the traceries above are Resurrection scenes featuring figures rising from their tombs, trumpeting angels, and probably Christ our Saviour and Redeemer.

The window has the wonderfully lustrous quality of medieval pot-metal glass. It is also notable for its depth and brightness of colour, as well as for its delightful symmetry on the levels of both composition and colouring. A programme of conservation began in 2012, with each panel of the window being taken to the workshop of Holy Well Glass in the city of Wells for careful cleaning and, where necessary, repair.

CARLISLE CATHEDRAL – East Window (1359)

Flowing Decorated tracery with stained glass of the Last Judgement from 1350s, attributed to Ivo de Raughton, lower panes on the life of Jesus by Hardman & Co. of Birmingham (1861), 17.6 × 8 m

The wonderful Curvilinear East Window of Carlisle Cathedral remains one of the largest and most complex examples of Flowing Decorated Gothic tracery in England. Its origins can be traced to the lengthy rebuilding works of the fourteenth century that followed a fire which took place in 1292 – lengthy because of frequent raids on the city by the Scots and because of recurrent outbreaks of the Black Death that killed at least a third of Carlisle’s population.

In 1359 John de Salkeld, a yeoman from Little Salkeld, near Penrith, donated 40 shillings ‘to make a window anew in the chancel’. The upper, medieval section of the surviving window is attributed to Ivo de Raughton and depicts the Last Judgement, a popular subject in the Middle Ages. Most of the lower glass of the window had disappeared by the mid-eighteenth century and been replaced by plain glass with a coloured border; there is no record of what imagery may originally have been on display.

By the mid-nineteenth century restoration work was urgently required, with the window tracery being described as ‘in a bad state in every respect’: ‘the glazing is so greatly dilapidated that in bad weather the rain pours in’. In 1861 Hardman & Co. of Birmingham were commissioned to refill the lower panes in memory of Hugh Percy, Bishop of Carlisle (1784–1856). The glass imagery depicts the life of Jesus.

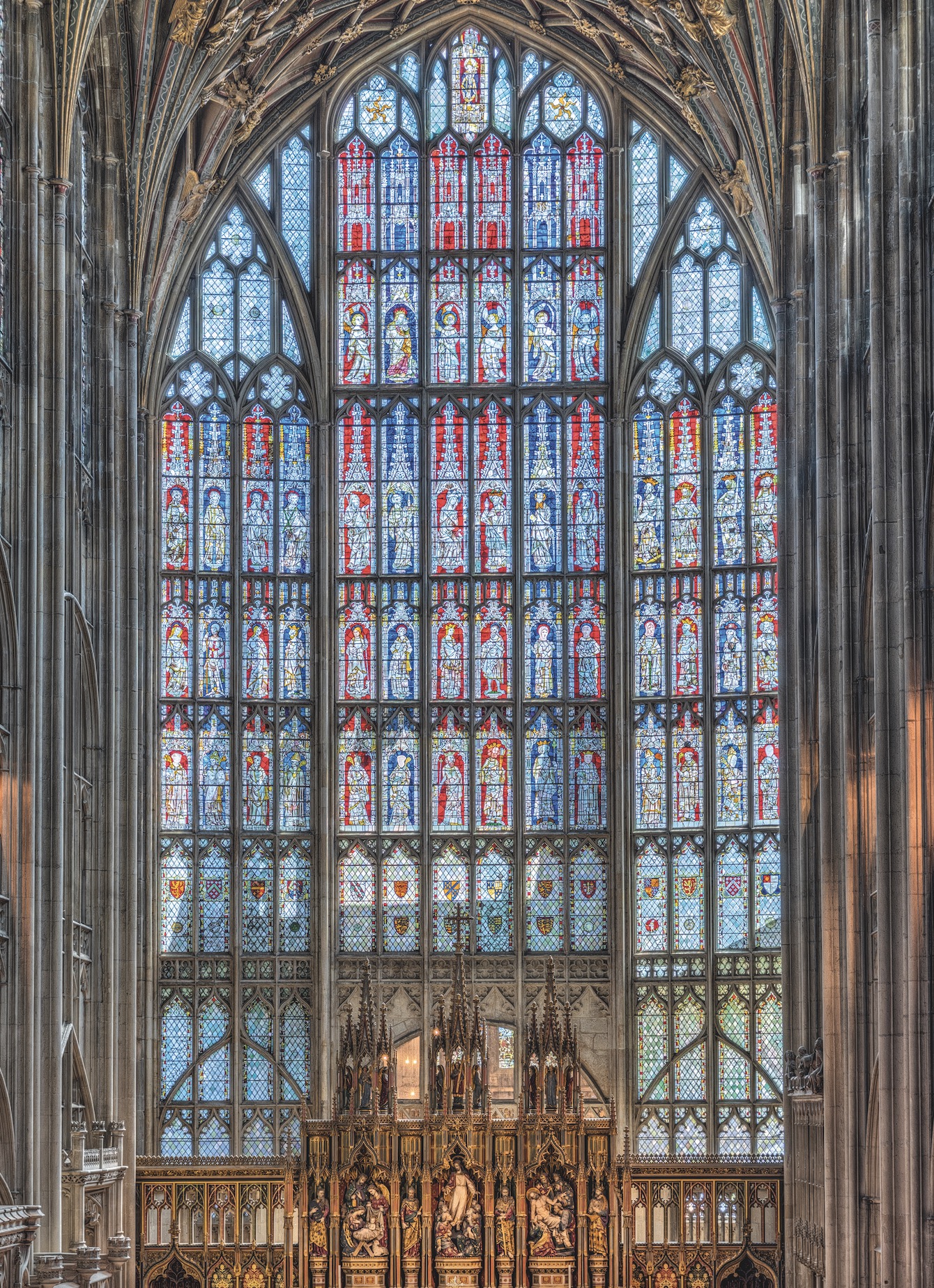

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL – Great East Window (c.1360)

Floor-to-ceiling tiered and canted window depicting the Church’s earthly authorities, saints, Apostles, Mary and Christ, and the heavenly realm of angels, 22 × 14 m (roughly the size of a tennis court).

The term ‘wall of glass’ is overused today, but at Gloucester it is a medieval reality. Between 1345 and 1355 the quire of St Peter’s Abbey (now Gloucester Cathedral) was remodelled to make it a fit resting place for King Edward II. As part of this Perpendicular remodelling the east wall of the Cathedral was demolished and a new giant window was installed.

Gone were the small, dark windows of the Norman apsidal east end, and in their place was glass reaching from floor to ceiling. This achievement is all the more impressive when we consider that the window was created and installed in the shadow of the Black Death, which had ravaged the population of England from 1348 onwards, wiping out a third of the population. Despite the vicissitudes of time, at least 70 per cent of the original 1350s glass remains in situ.

The window’s central focus is the Coronation of the Virgin Mary, but it also depicts a harmonious and well-ordered world. Using only four colours of glass, the medieval artists brought to life the temporal and spiritual rulers of the Earth, as well as the saints, Christ, Mary, the Apostles and the angels.

They also incorporated a collection of coats of arms at the base representing the lords and the people. These coats of arms are the origin of the name that began to be used in the twentieth century: ‘the Crécy Window’. Subsequent research on the heraldry has made clear that the coats of arms are not limited to those of individuals who fought at the Battle of Crécy (1346), but that they are rather those of the great families at Edward III’s court who supported him in his many military campaigns. The window is therefore once again referred to as the ‘Great East Window’.

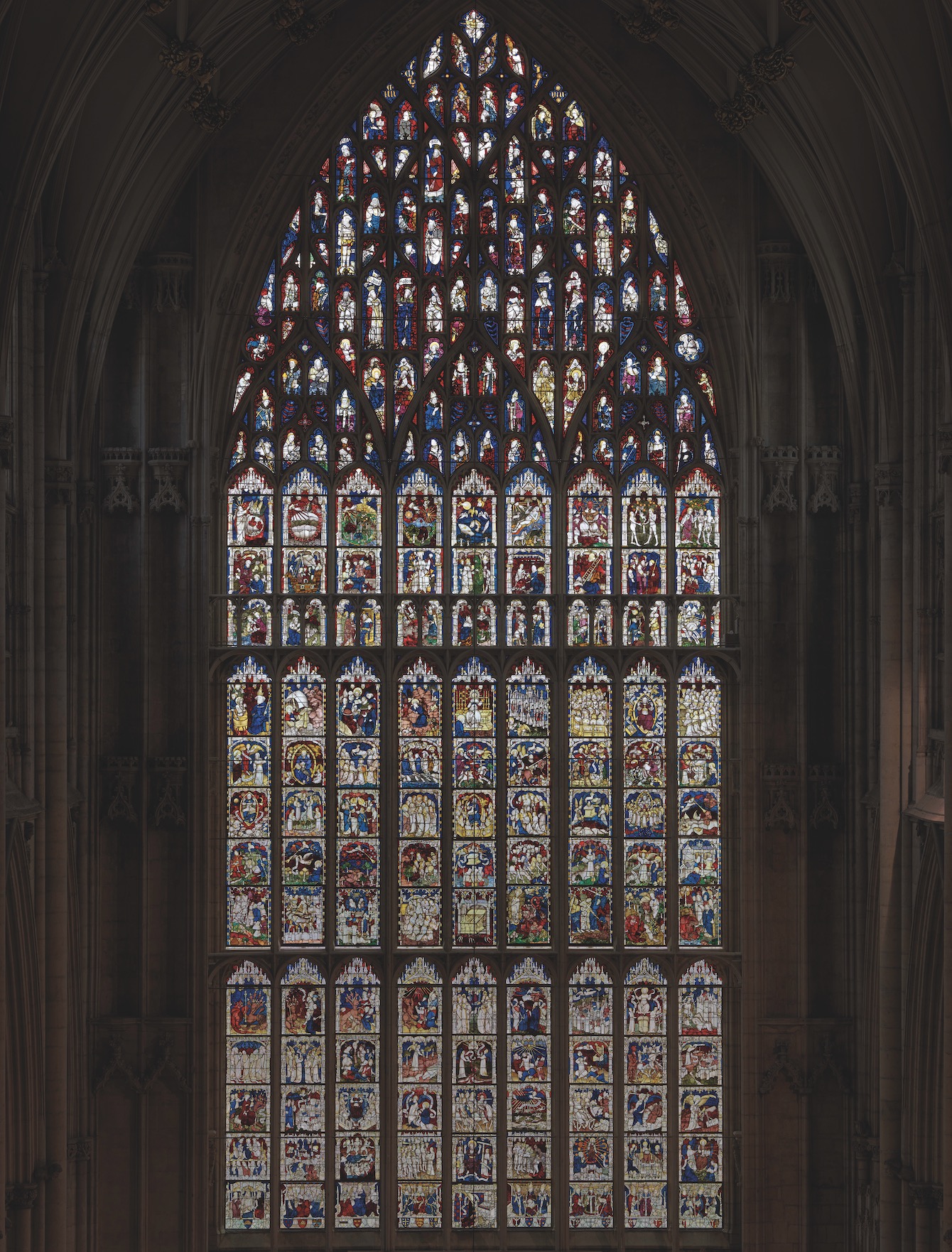

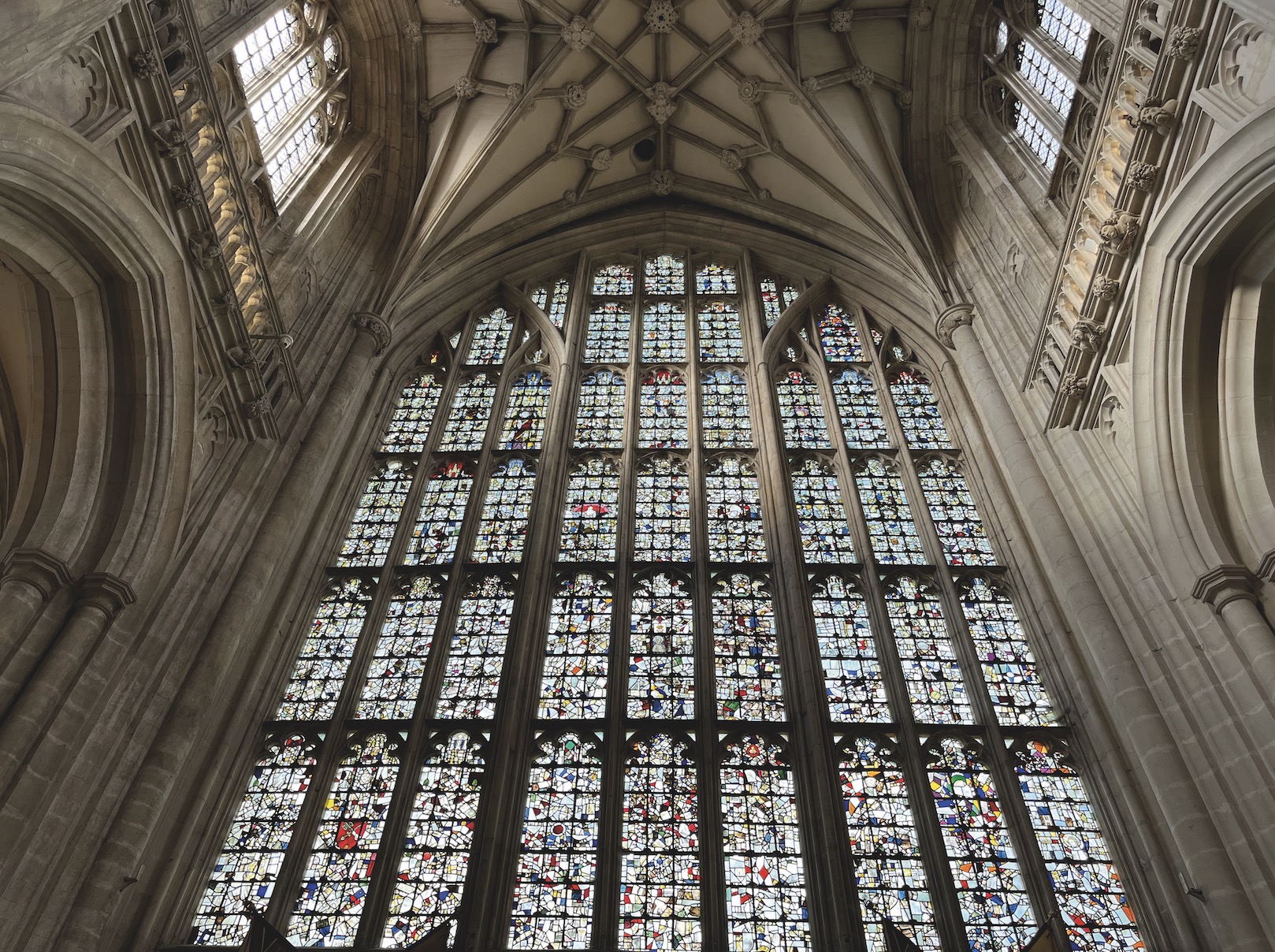

YORK MINSTER – Great East Window (1405–8)

117 narrative panels in rows of nine from the Creation to the Apocalypse, with over 300 panels in total, by John Thornton of Coventry (active 1405–33), 23.2 × 9.8 m

In the winter of 1405, as a political crisis rocked the city of York, the Cathedral Chapter entered into a contract for the creation of the largest expanse of stained glass ever made in medieval England.

The project was breathtakingly ambitious, spanning as it did both the beginning and the end of human history – from Creation as it is related in the first book of the Bible (Genesis), to the end of the world and the second coming of Christ as explored in the last book (Revelation – known as the Apocalypse in the Middle Ages). With the Archbishop of York having recently been executed for treason and the city’s civic privileges having been suspended by the King, apocalyptic imagery must have seemed all too relevant to the surrounding community.

No one had ever attempted an Apocalypse in stained glass before, and the window, completed in 1408, is a tribute to the audacity and imagination of the medieval Cathedral community that commissioned it, as well as being a monument to the genius of the window’s creator, John Thornton, the master glazier of Coventry to whom the commission was entrusted. Although Thornton is known to have been a glass-painter, it was his reputation as a designer of rare talent and a project manager of exceptional skill that commended him to his York clients.

Not only was he able to develop an action-packed narrative out of one of the most challenging books of the Bible, he was also able to create a masterpiece in the stained-glass medium, delivered on time and on budget.

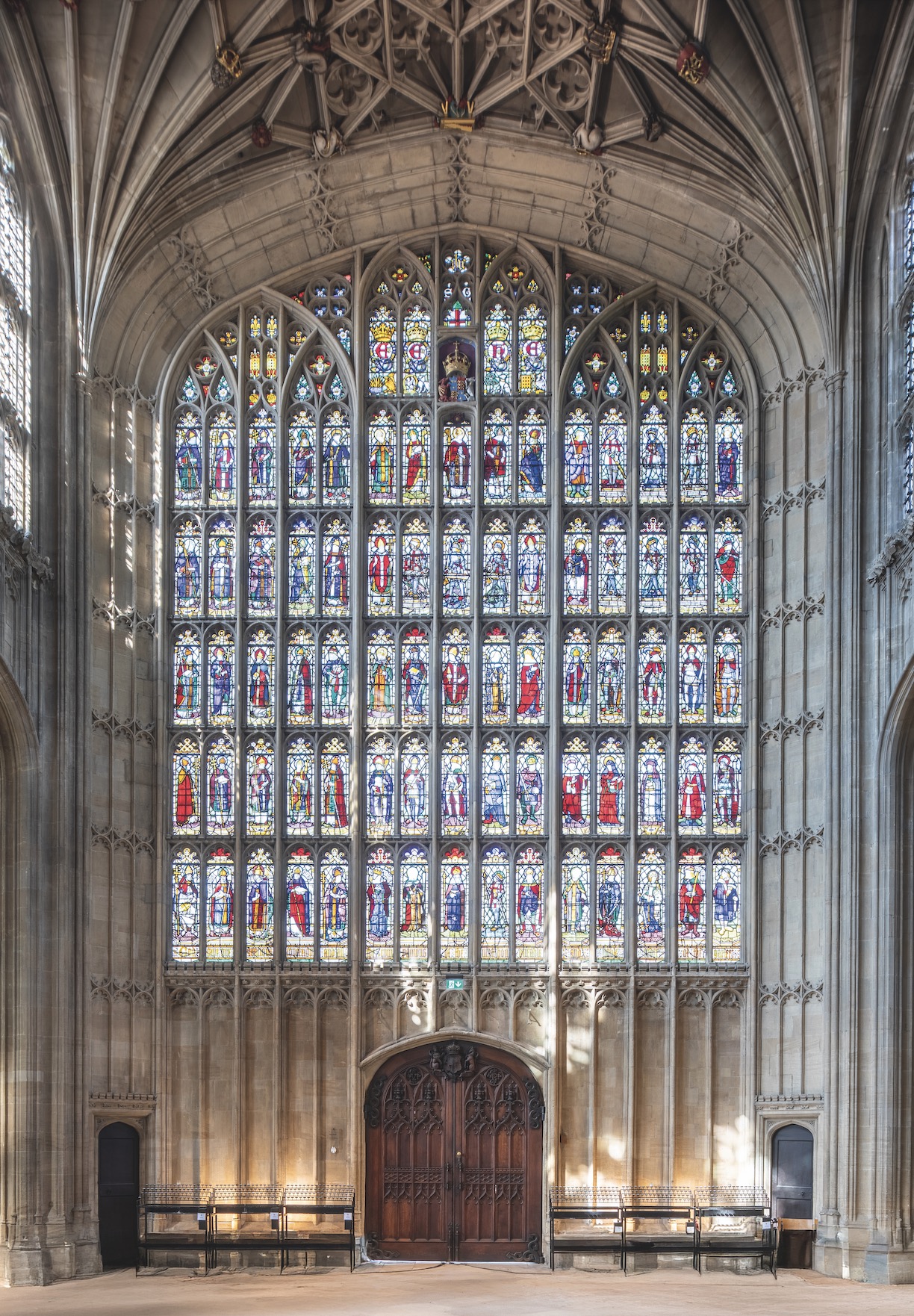

ST GEORGE’S CHAPEL, WINDSOR CASTLE – West Window (constructed c.1500, glass installed by 1509)

Seventy-five lights containing stained-glass painted figures, of which sixty-five survive from before 1509, including several by Flemish glazier (and King’s glazier from 1505) Barnard Flower (d.1517), 11 × 9 m

The West Window of St George’s Chapel dominates the nave. Containing over 500 square feet of stained glass, it features seventy-five depicted figures: twenty-five popes, seventeen kings, twelve knights, ten bishops or archbishops, eight saints and three ‘civilians’. Currently the figures are grouped by type, but this was not always the case.

The earliest glass in the window probably dates from shortly after the construction of the Chapel began in 1485, though it is possible that it was originally intended for use in the east end. The glass in the West Window appears to have been removed during the Civil War, and it was not until 1767 that it was filled with ‘such Painted Glass as [could] be collected from other parts of the Chapel’. A full restoration was carried out in 1841–2, and seven new figures were added by Thomas Willement. Willement also changed the window’s plain white backgrounds to decorated ones and created some ‘composite’ figures from damaged glass, as well as inserting new glass to repair broken sections.

The most intriguing figures are the civilians. One is a mason and is assumed to be William Vertue, the master mason during the Chapel’s construction. Another holds a scroll, and may represent the Clerk of Works. His head has been replaced by that of a bearded king. The third civilian has a purse hanging at his belt. It may be that all three of these figures were a collaboration between Adrian of Mechlin and Barnard Flower, the King’s glazier who also worked at Fairford Church and King’s College, Cambridge.

The inclusion of the civilian figures in the procession of kings, popes and bishops reminds the viewer of the process of the building of the Chapel and the labour that went into its construction.

ST EDMUNDSBURY CATHEDRAL – Susanna Window (c.1500)

Apocrypha story of Susanna and the Elders, containing glass from Rouen in lower section with English glass at the top, west end of south aisle, 6.7 × 3.1 m

The Susanna Window contains the oldest glass in St Edmundsbury Cathedral – it is thought to have been made in Rouen, France, in the early sixteenth century. The glass was collected from other parts of the building and placed in the chancel window in the 1820s, when the Cathedral was the Parish Church of St James. Later in the nineteenth century it was moved to its present location in the far south-west corner.

The need for a new window in that part of the building was due to the demolition of an adjoining structure. Previously, a coffee house had joined the church’s south side to the twelfth-century Norman Tower that stands 10 metres to its left. The Norman Tower was a gateway to the Abbey of St Edmund during its heyday as a European pilgrimage destination. The coffee house was demolished in order to facilitate the restoration of the Norman Tower in the nineteenth century, and its removal led to a need for an additional window in the Cathedral.

The bottom half of the window shows the story of Susanna and the Elders from the Apocrypha, in which the Elders hide in Susanna’s garden and falsely accuse her of adultery. When she is brought to trial, however, the young prophet Daniel defends her, exposing the inconsistencies in her influential accusers’ story so that, in the end, it is they and not Susanna who are stoned to death. In the panels above are heads of kings and prophets; the glass depicting St John is a later addition.

LICHFIELD CATHEDRAL – Herkenrode Glass (created 1530s, installed in Lichfield Cathedral 1805)

340 panels using brightly coloured pot-metal and flashed glass, with grisaille, silver-stain and enamel paints, in twelve windows, seven in east-end Lady Chapel, window height c.11 m

The eastern windows of Lichfield Cathedral are to be found in the Lady Chapel. They house the sixteenth-century coloured glass which started life in the Cistercian convent in Herkenrode in modern Belgium and was brought to Lichfield by Brooke Boothby, a local landowner, in 1802. The glass had been taken down for safety by the nuns when they left the abbey during wartime.

The windows depict the Annunciation, the events of Passion Week, the Resurrection, the Ascension, Pentecost and the Last Judgement. Two of the panels portray the donors who paid for the glass, and are shown in their oratories with their patron saint. In one section the Abbess stands in front of Herkenrode Abbey with her crozier and her flock of nuns The panels provide fascinating insights into the Renaissance period.

When the glass arrived in Lichfield it had to be fitted into the existing fourteenth-century openings. This has led to a certain eccentricity in the telling of the Gospel story, such that the viewer is required to take on an active role by tracing the sequence of events – a sequence which is arranged around the central image of the resurrected Christ breaking bread with his disciples. That scene is placed above the altar.

In recent years the glass has been cleaned and conserved, meaning that the vibrant colours and the details of this magnificent artwork can now be fully appreciated. One other unexpected benefit is that on sunny days the morning light in the chapel causes the colours to fragment, so that the floor, the walls and anyone standing in the chapel become part of a wonderful multi-hued pattern.

CHRIST CHURCH CATHEDRAL, OXFORD – Jonah Window (1631)

Flemish-style stained and painted glass by Abraham van Linge (active c.1623–42), survived the Civil War, north aisle, 4 × 2 m

The early 1630s saw a major reordering of Christ Church Cathedral, in the course of which a set of windows was commissioned from the Dutch stained-glass artists Abraham and Benjamin van Linge.

A lengthy poem published in 1656 describes the windows, which included representations of key events and figures from the Scriptures – among them the fall of humanity, Abraham and Isaac, Jonah, the Nativity, the Last Supper and the Crucifixion.

Within twenty years, however, all but one of the windows had been reduced to fragments. A decree issued on 2 June 1651 demanded that ‘all Pictures representing god, good or bad Angells or Saints shall be forthwith taken downe out of our Church windows, and shall be disposed for the mending of the Glasse that is out of repaire in any part of the Colledg’. The only window that survived was Abraham van Linge’s depiction of Jonah sheltering under his gourd (Jonah 4:6), watching and waiting for the hoped-for destruction of Nineveh.

One theory as to why this particular window survived is that, on account of his being neither God, an angel, nor a saint, but merely human, Jonah was considered to be an acceptable subject. Perhaps the Puritans considered his faults – especially his failure to accept the authority of God – a worthy object lesson.

The window also survived the Victorian restoration of Gilbert Scott, and today it stands as part of a range of stained glass extending from the Middle Ages to the twenty-first century and encompassing both biblical (e.g. Thomas Denny’s 2025 Prodigal Son) and hagiographical subjects (e.g. Edward Burne-Jones’s St Frideswide window). This breadth reflects a central feature of the story of Jonah (one that perhaps escaped the Puritan extremists): the fact of God’s essential compassion and mercy.

WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL – Great West Window (glass replaced after 1660)

Window built c.1375, fragments of medieval glass reinstated in the late seventeenth century, 16 × 10 m

The Great West Window of Winchester Cathedral, with its jumbled imagery and chequered history, is a magnificent sight. It was originally glazed in c.1375–84 under the direction of Thomas of Oxford, at a time when the nave was being remodelled in the Gothic style. It would have been part of the overall vision for the Cathedral, allowing light to flood into the building and enhancing the glorious vaulting of the restyled nave.

But the window no longer survives as originally designed. It was damaged in the Reformation and then again during the seventeenth-century civil wars. Its shattered pieces were gathered, along with fragments from other windows. These were repurposed in calmer times to create the mosaic of coloured glass that we see today.

Much effort has been devoted to analysing the original scheme. The window is arranged in three panels, with each panel being three lights wide. The side panels would have depicted the Apostles and the prophets, while the uppermost panes of the central panel would have shown scenes from the life of Christ. A striking image of the crowned head of Christ survives; also discernible are St Peter with his keys, a sleeping soldier in chainmail, and various bearded and cherubic heads. There are panes showing architectural elements and ecclesiastical robes, a cheeky lion, a swan on its nest, wheels and feathers, scrolls, and words relating to the Annunciation and taken from the Apostles’ Creed.

People often gaze at the window, seeking out individual features or trying to reconstruct the medieval form of the whole. It may never be possible to do this with accuracy, but the window remains one of the great glories of the building – a powerful example of beauty emerging from brokenness, and a profound source of wonder and inspiration.

ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL, LONDON – Christopher Wren’s use of clear glass throughout St Paul’s Cathedral (1710)

Clear-glass windows around the dome and in the south-west tower, architect Christopher Wren (1632–1723)

Christopher Wren’s innovative use of clear-glass windows in St Paul’s Cathedral and his City churches exemplifies his artistic mastery and theological intent. Wren’s approach was not merely aesthetic; it was also deeply tied to the evolving identity of the reformed Church of England in the seventeenth century. By allowing clear divine light to infuse these sacred spaces, Wren departed from the shadowy interiors of medieval Catholic churches, emphasising clarity, understanding and direct communion with God.

A striking example of this approach can be seen in the major set of windows encircling the base of St Paul’s great dome. These expansive clear-glass openings bathe the interior in natural light, lifting the eye heavenward and reinforcing the Cathedral’s grandeur. The effect is both spiritual and structural, as the dome appears to float above the nave, its architectural brilliance revealed in full detail. When the sun is low, the display of chiaroscuro around the pillars and architraves and across the memorials and the black and white tiled floor is subtle in its spirituality.

In the south-west tower of St Paul’s, large clear-glass windows illuminate the beauty of the geometric staircase, with the interplay of light and shadow highlighting the exceptional craftsmanship of Jean Tijou’s ironwork and demonstrating how Wren skilfully balanced functionality with elegance. Two windows also light up the Cathedral’s library chamber and triforium via curved internal window casements.

Beyond St Paul’s, Wren’s City churches further showcase his commitment to clear glass. In contrast to the stained glass of the pre-Reformation period, his designs prioritised unfiltered light, symbolising the reason and transparency that defined the Church of England’s post-Reformation Renaissance ethos, which placed man at the centre of things as well as Almighty God. By flooding his churches with divine light, Wren transformed London’s ecclesiastical landscape.

Above : Well-spaced clear-glass windows illuminate the south-west tower and Wren’s geometric staircase, with its exquisite ironwork by Jean Tijou.

Above : In the south-west tower, curved internal windows let borrowed light into the library and triforium.

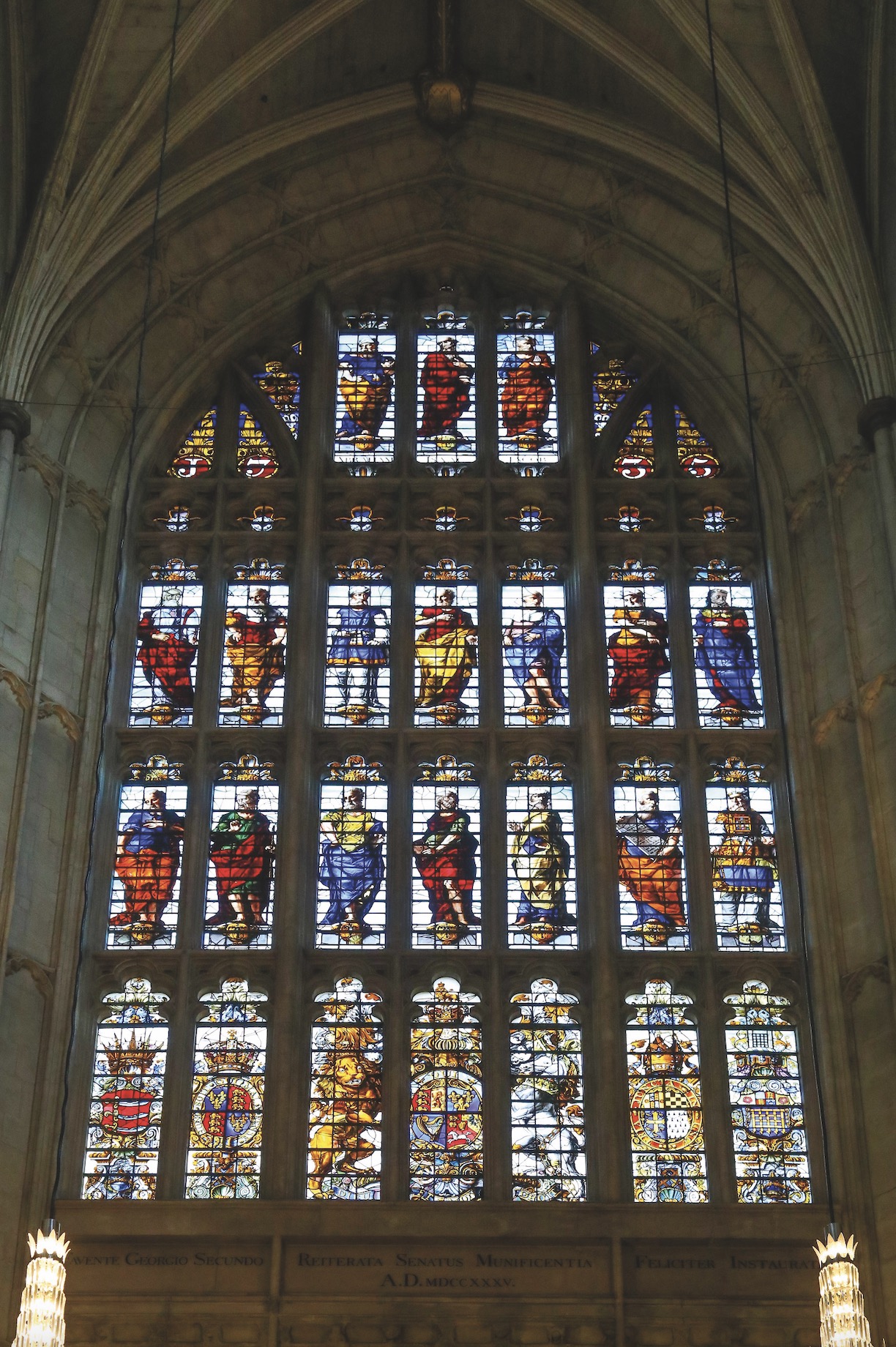

WESTMINSTER ABBEY – Great West Window (1735 – depicted in top lights)

Thought to have been designed by James Thornhill (1675–1734), made by William Price (d. 1765), 13.7 × 9.4 m

The Great West Window of Westminster Abbey (completed in 1735) is believed to have been designed by James Thornhill and executed by the glassmaker William Price. This remarkable work, which depicts Abraham, Isaac and Jacob with the Twelve Tribes of Israel, is a rare example of early Georgian stained glass and represents an intriguing moment in the evolution of religious imagery in the reformed Church of England.

The window’s subject matter reflects the doctrinally cautious approach of the early eighteenth-century Church – thereby marking a contrast with the medieval windows lost during the Reformation. Rather than depicting saints or scenes associated with pre-Reformation devotional practices, the window presents direct biblical narratives, demonstrating the gradual reintroduction of religious imagery in Anglican worship spaces.

Thornhill was a key figure in early Georgian art and architecture, following in the footsteps of Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor. Best known for his Baroque murals in the Painted Hall at Greenwich and the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, Thornhill also contributed to Westminster Abbey’s Gothic fabric. He and Price had previously collaborated on the north transept’s Rose Window, making the West Window their second major stained-glass project for the Abbey.

The Great West Window is notable for its grand scale and striking composition. The lower panels display the crests of arms of King Sebert, Queen Elizabeth I, King George II, Joseph Wilcocks (the Dean of Westminster), and the City of Westminster. The glasswork was likely executed using enamel-painted glass, which allows for detailed pictorial representation and vibrant colour.

Set within the architectural context of Hawksmoor’s west towers, the Great West Window exemplifies Westminster Abbey’s eighteenth-century transformation – into a space that was both a site of commemoration and a place where artistic and religious traditions were tentatively reinterpreted for a new age.

ELY CATHEDRAL – St Peter Window (1770)

‘Best thick crown Bristol glass’ for enamel-painted plain glass sheets by James Pearson (c.1740–1838), north nave triforium, 2.9 × 2.4 m

In a window in the north nave triforium of Ely Cathedral, today only visible from the Stained Glass Museum gallery, is a figure of St Peter holding keys and several heraldic shields. It dates to 1770 and was originally part of the incomplete glazing scheme for the five-lancet East Window of the choir commissioned by Matthias Mawson, Bishop of Ely from 1754 to 1770. These rare examples of eighteenth-century painted glass are important remnants of a major reordering of the Cathedral’s east end undertaken in the Georgian period.

Bishop Mawson commissioned the artist James Pearson, a Dublin-born glazier based in London, to produce the new window. It was his earliest recorded commission. The design was to feature full-length figures of St Peter, St Etheldreda and St Paul – with shields below representing the Royal Arms and the See of Ely – in the upper compartment. The outer lights were to be filled with arms of the Cathedral prebendaries. The lower compartment of the window was to feature a Nativity scene with angels descending in attitudes of joy, with the Evangelists appearing in the side lights.

The contract with Pearson specified that the final design and painted glass should be approved and inspected by Mawson or an appointed representative, and that the window should be made of the ‘best thick crown Bristol glass’. Pearson agreed to undertake the design, making, carriage and installation for £200. However, when Mawson died in November 1770 the East Window was left incomplete. The completed figure of St Peter was ultimately reset alongside some of the arms of the prebendaries in the north triforium when plans for a new East Window were being devised in the 1840s as part of the extensive Victorian restoration of the building.

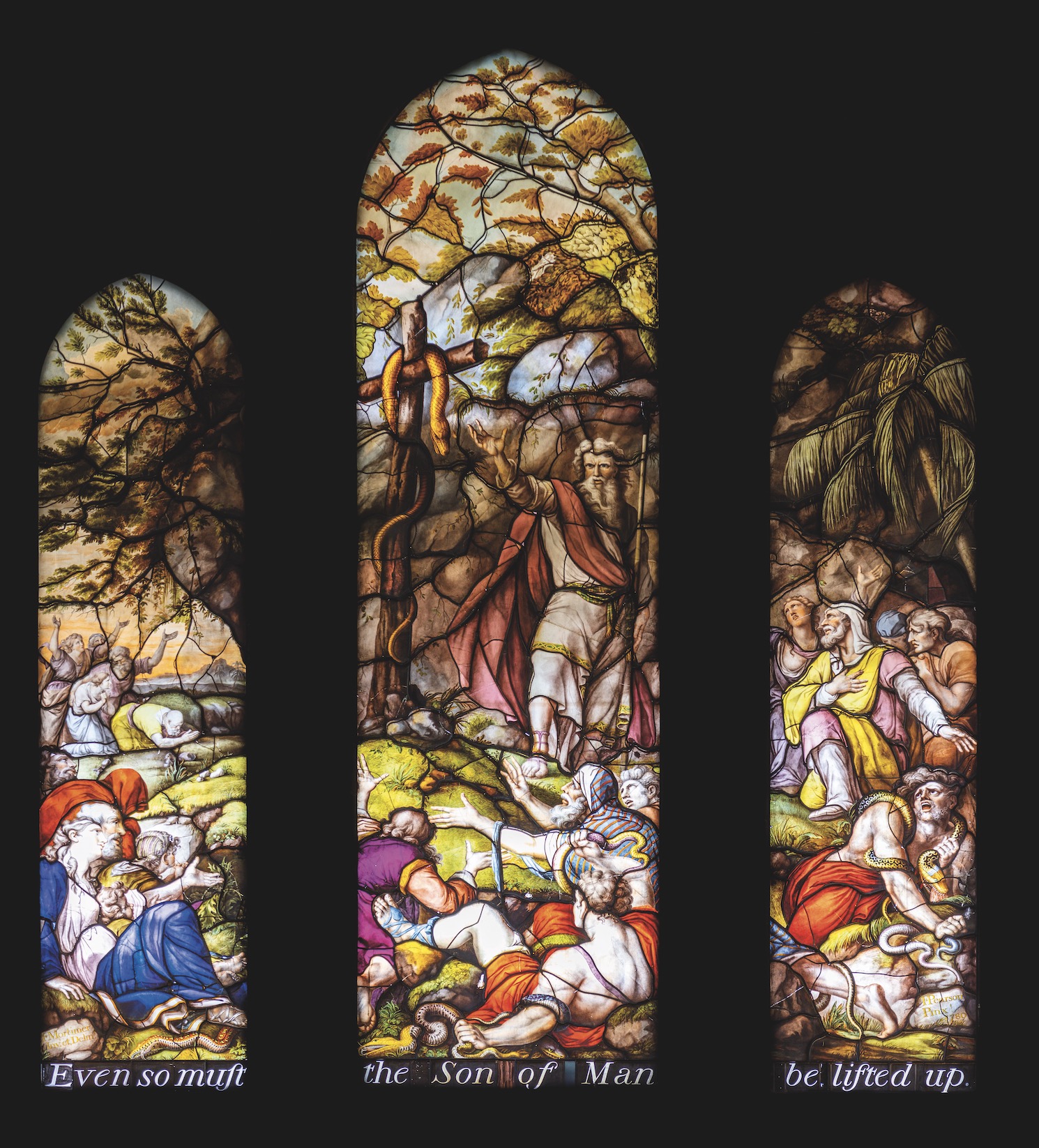

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL – Moses Window (1781)

Plain crown-glass sheets painted in coloured enamels, with lead and copper tie bars, by James Pearson (c.1740–1838) from a painting by John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–79), eastern gable, 5.9 × 1.8 m (central light) and 4.8 × 1.2 m (sides)

In the eastern gable of Salisbury Cathedral, above the high altar, is a three-light window by James Pearson depicting ‘Moses and the Brazen Serpent’. It was installed in 1781 and was based on a painting by John Hamilton Mortimer, whose death delayed the delivery of the cartoons by six months. When the window was finally finished, it was exhibited by Pearson at the Pantheon in London prior to its installation at the Cathedral. The unusual methods involved in its construction attracted significant interest.

The window is made up of large sections of crown glass and is only 1–2 mm thick. The detail was painted in coloured enamels that were fired in a kiln to fix them onto the glass surface, and the sections are leaded together. Copper ties join the leadwork to a wrought-iron frame, which is screwed to the stonework at its edge.

The lights were removed and re-leaded by Salisbury Cathedral’s Stained Glass Department between 1979 and 1983, but, in a testament to Pearson’s skill, very little deterioration of the painted detail had taken place. External isothermal glazing was provide further protection.

The window depicts the Old Testament scene in which God’s people are attacked by snakes. Moses responds by fashioning a serpent of bronze and raising it on a pole; all who look upon the bronze serpent are saved. Christian tradition understands this as a foreshadowing of the Crucifixion of Jesus. He too is raised – upon the cross – and all who place their trust in him are saved. Hence the choice of biblical text at the bottom of the window: ‘just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whosoever believes in him may have eternal life’ (John 3:14–15).

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Picture credits – York Glaziers Trust © Chapter of York; David Brook; Andy Marshall; Mel Howse and Vitreous Art Ltd; Portsmouth Cathedral; Marcus Green; Lichfield Cathedral; The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral; Dan Beal; Lynne Alcott Kogel; Wells Cathedral; Holy Well Glass; Kevin Lewis; Tom Soper Photography; Rob Scott; Dean and Chapter of Christ Church, Oxford; Gordon Plumb; Winchester Cathedral; Janet Gough; Kevin Caldwell © Off the Rails Australasia Pty Ltd; Steven Jugg; Declan Spreadbury/Salisbury Cathedral; Gordon Taylor; Bradford Cathedral/Philip Lickley; Chris Parkinson; Gill Poole; Chris Hutt; Paul Barker; Christopher Guy/Worcester Cathedral; Mark Charter; © David Whyman; Clive Tanner; Peterborough Cathedral; Bill Smith/Norwich Cathedral; Peter Hildebrand/Visit Stained Glass; Luke Watson; Patrick Fitzsimons; Bristol Cathedral; David Pratt; Aaron Law; Manchester Cathedral/Nathan Whittaker; Liverpool Cathedral; Gareth Jones Photography; Salisbury Cathedral; St Albans Cathedral; Dr Chris Brooke; Southwell Cathedral Chapter; Blackburn Cathedral; Richard Jarvis and Aidan McRae Thomson of Norgrove Studios Ltd.