Divine Light – The Stained Glass of England’s Cathedrals – The Modern Age 1920 to the present

Glass production is an ancient art form, but it has remained consistently popular over the past hundred years or so. Glassmaking has also continued to evolve: this section is bookended by women artists (Chester and Durham), and the work of female practitioners is discussed in a number of other entries as well. The Glass House studio in Fulham was to become home to a number of women artists, including Moira Forsyth (Guildford and Norwich).

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

The two world wars provided the occasion for installations such as the Dunkirk and D-Day Windows at Portsmouth Cathedral. Bomb damage furthermore necessitated the replacement of many medieval and Victorian windows.

War-damaged Coventry Cathedral was completely rebuilt in a modern style in the space of five years by Basil Spence. Spence worked with artists such as Lawrence Lee – who with his students from the Royal College of Art created experimental abstract windows – and John Piper, who created the astonishing Baptistery Window with Patrick Reyntiens.

Compared with Continental Europe and the Catholic Church, the Church of England has commissioned relatively little abstract glass – although compelling examples at Derby, Blackburn and St Albans are all included here. Christopher Webb’s windows at Sheffield Cathedral meanwhile illustrate theological concepts and biblical and local stories in a more traditional style, combining draughtsmanship with sophisticated glass techniques.

Freedom of style and dynamic design in six new West Windows by Antony Hollaway have added intense colour and joy to the Perpendicular Manchester Cathedral. New subject matter is evident from the Prisoners of Conscience Window at Salisbury, and from the treatment of both personal and historical themes – with King Richard III presented as Everyman – in Thomas Denny’s windows at Leicester. Denny, whose work features in several cathedrals, is notable for his exceptionally imaginative narrative and reflective compositions, as well as for his use of traditional glassmaking techniques and extensive painting and etching.

CHESTER CATHEDRAL – Cloister Windows (1920s)

Thirty-four windows with 130 lights, presented as an Anglican calendar, most from the studio of F.C. Eden (1864–1944) and A.K. Nicholson (1871–1937), alongside designs by Chester artist Trena Cox (1895–1980), cloister window 2.4 × 0.4 m

The Cloister Windows at Chester Cathedral are at the heart of the monastic site that was once home to the Benedictine Abbey of St Werburgh. Their unique scheme of glazing depicts the liturgical calendar.

That scheme was part of the vision for Chester Cathedral of Frank Selwyn Macaulay Bennett, Dean of Chester 1920–37. Dean Bennett believed that Chester Cathedral should be ‘open without fence or fee’, and so removed the entrance fee for visitors to the Cathedral – making him the first Anglican dean to do so. He saw the value in caring for history and heritage, and he quickly set about restoring and developing parts of the Cathedral that had fallen into disrepair, including the cloister and garth. A glazing scheme for the cloister seemed to Bennett to accord with the medieval appearance of the space, which provides a warm and quiet area in which visitors can walk and reflect.

The scheme for the Cloister Windows takes the Anglican liturgical calendar in use in the early twentieth century as its thematic guide, with a section on the south walk reserved for English post-Reformation ‘saints’. The majority of the window were commissioned from the London studios of Frederick Eden and Archibald Nicholson. Two four-light windows depicting historical figures and relating to the Abbey of St Werburgh were commissioned from Arts and Crafts artist Trena Cox, a Chester resident.

As a scheme of windows on a single theme visible at eye level, the Cloister Windows were and continue to be immensely popular with pilgrims to Chester Cathedral. They provide an opportunity to ‘walk’ the liturgical year, to contemplate the changing seasons, and to admire the skill employed to make Dean Bennett’s project a reality.

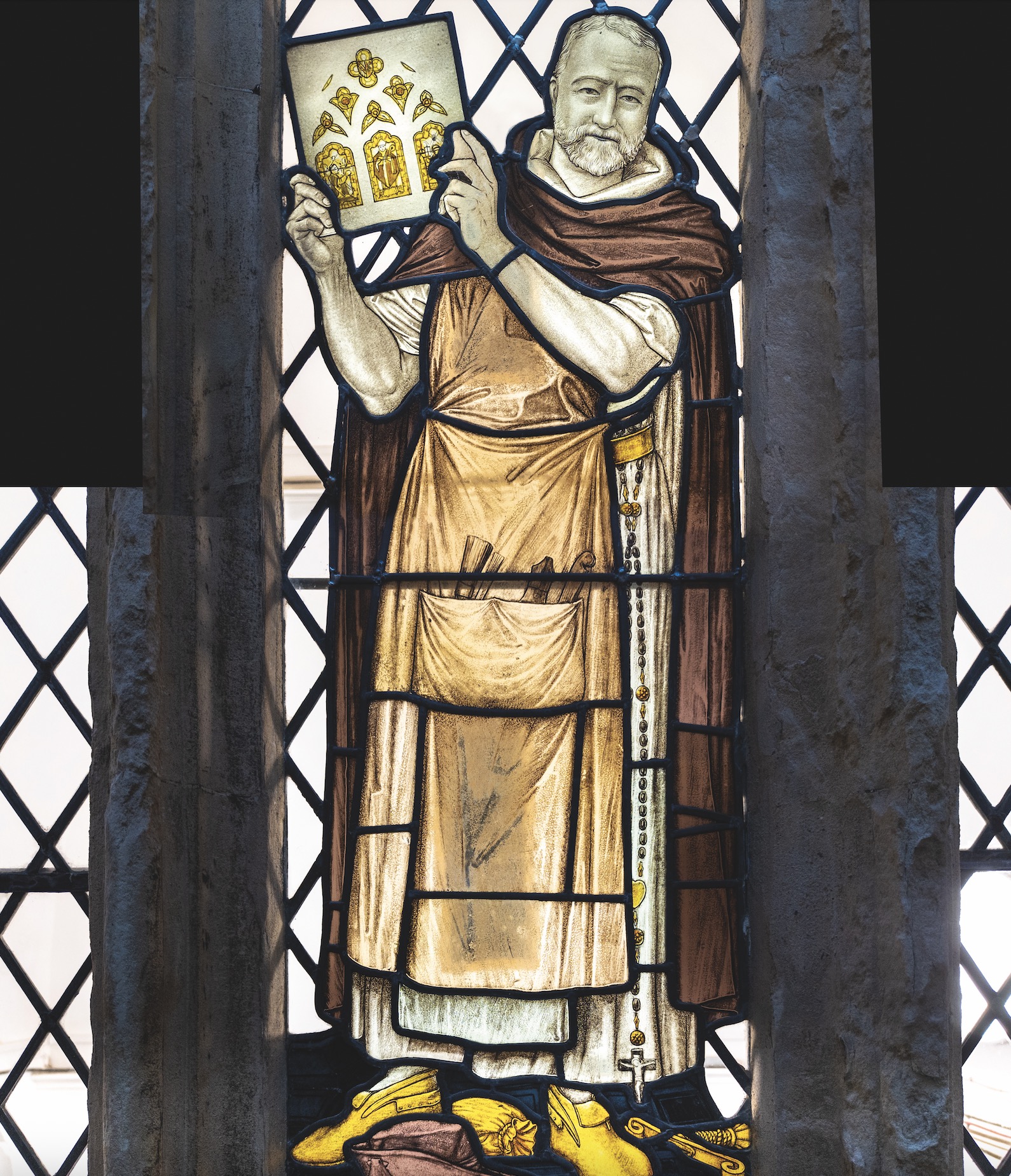

EXETER CATHEDRAL – Drake Memorial Window and Blessed James of Ulm, Patron of Glaziers (1921)

Commemorating Frederick Drake, Cathedral glazier for forty years (1880–1920), Friends’ Cloister Gallery, above door of former Chapel of the Holy Ghost, 3.1 × 1.8 m (full window), 1.6 × 0.4 m (figure and inscriptions)

Three generations of the Drake family worked as glaziers at Exeter Cathedral, and all three are associated with this window. In 1921 Frederick Morris Drake installed a window in the outer wall of the passage connecting the south tower with the chapter house to commemorate his father, Frederick Drake – who had been appointed Cathedral glazier in 1880 – and his foreman glazier, William Bellringer. Its central figure is Blessed James of Ulm, the patron of glaziers, who was surrounded by earlier glass that had recently been returned to Exeter Cathedral by the Architectural Association.

After the Second World War the window was restored by Frederick’s granddaughter, Daphne, who added a dedication to her father, Frederick Morris, and her uncle, Wilfred (also a glazier). The earlier glass was used elsewhere in the Cathedral.

After the Drake memorial glass was repaired and conserved in 2024, it was reinstalled facing the opposite direction, with back lighting, since the wall containing the window had become an internal wall of the newly constructed Friends’ Cloister Gallery (built on the footprint of the medieval east cloister and designed by Camilla Finlay of Clews Architects).

Blessed James was a fifteenth-century stained-glass craftsman who entered the Dominican order. Frederick Drake’s face is used in the window’s portrayal of Blessed James, here shown wearing Dominican robes and an apron with glazier’s tools in the pocket.

In this remarkable composition, the vidimus being held is that of the Grandisson Window which Frederick Drake designed for Exeter Cathedral. Located over the south door in the west front, it commemorates John Grandisson, Bishop of Exeter 1327–69.

Unfortunately, Drake’s Grandisson Window was destroyed in 1942, but in 1949 Lyon John Rosevear used Frederick Drake’s original cartoon to recreate it.

GUILDFORD CATHEDRAL – East, Rose Window (commissioned 1939 – dedicated 1952)

Gifts of the Holy Spirit, designed by Moira Forsyth (1905–91) in Norman slab glass and made in the Glass House, Fulham, above high altar, diameter 3.2 m

The eyes of visitors arriving at the West Door of Guildford Cathedral are immediately drawn to the striking East, Rose Window. It was designed by Moira Forsyth on instructionsfrom the Cathedral architect Edward Maufe. The window signifies the Cathedral’s dedication to the Holy Spirit.The central panel shows the Holy Spirit as a descending dove, below which is the legend ‘Veni Creator Spiritus’ (‘Come, Holy Spirit’).

In the outer border beyond the depicted Attendant Angels appear the Latin names of the Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit: Pietas (True Godliness), Consilium (Counsel), Intellectus(Understanding), Sapienta (Wisdom), Fortitudo (Steadfastness), Scienta (Knowledge) and Timor Domini (Fear of the Lord, or Contemplation).

Forsyth’s work is shot through with a seriousness of theological intent and is underpinned by the extreme care she took at the design stage. She drew upon tradition as well as such Arts and Crafts-inspired techniques – she trained at the Royal College of Art under Martin Travers – as the use of slab glass. Her windows also feature heavy cross-hatching and lettering.

Forsyth related the circumstances of the window’s creation: ‘The first window of any importance I was commissioned to make was the East Window for Guildford Cathedral of which only the Crypt had been built at the time … the window was made under extreme difficulties. The first bombs on London damaged our glass studio (Lettice Street) and I had to restore what I could of the cartoon and complete the glass sections, which were stored in the crypt. Only when the Cathedral was completed did I realise how high the window was in the structure and [that it] looked comparatively small … but as the glass was all Norman slab (alas no longer available) it does radiate enough colour to make it intelligible.

SHEFFIELD CATHEDRAL – Te Deum Window (1948)

Designed by Christopher Webb (1886–1966), Chapel of the Holy Spirit, window 7 × 4 m

The parish church of Sheffield became a cathedral in 1914. Shortly afterwards, a scheme to enlarge the building was prepared by Sir Charles Nicholson and partially carried outfrom 1936 onwards. Although the scheme was eventually replaced by a less ambitious programme, its surviving buildings contain sixteen windows designed between 1935and 1948 by Christopher Webb.

Many of Webb’s windows in the Cathedral depict episodes and figures from the city’s history. His finest work, however, is the Te Deum Window in the Chapel of the HolySpirit. Completed in 1948, it would have been the liturgical East Window of the Lady Chapel in Nicholson’s scheme. The chapel is now dedicated to the Holy Spirit, and its chief gloryis Webb’s magnificent interpretation of the fifth-century Te Deum hymn. The window is a memorial to George Campbell Ommanney, vicar of the adjoining parish of St Matthew,Carver Street from 1882 to 1936. Father Ommanney was a leading Anglo-Catholic priest whose devoted ministry in his deprived parish wonadmiration even from those of very different theological outlooks from his.

The Te Deum is a hymn of praise to God from all created beings. At the centre of the window is Christ in Majesty – ‘thou art the King of glory’, as the hymn says – placed above the Virgin and Child (‘thou didst not abhor the Virgin’s womb’). Close to Christ are red-winged angels – cherubim and seraphim – and in other lights we see prophets, Apostles(each with their traditional attributes), martyrs, and ‘the holy Church throughout all the world’. Interestingly, numbered among the martyrs are Bishop James Hannington, missionary to Uganda, and Jan Hus. From the modern global Church we see Archbishop William Temple, Bishop Philip Lindel Tsen (China) and Bishop Vedanayakam Samuel Azariah (India).

BRISTOL CATHEDRAL – Windows in the East Walk of the Cloister (1953)

Seven cloister windows dating from the sixteenth century, reglazed in 1950s incorporating medieval, Victorian and 1950s decorative glass by Arnold Wathen Robinson (1888–1955), each three-light window 1.9 × 1.4 m

Much of the medieval glass in Bristol Cathedral was blown out in the Bristol Blitz of January 1941. Some of the rescued fragments were included in a schemeto glaze the cloister that was carried out in 1951. The scheme tells the story of the Augustinian abbey on which the Cathedral was founded, with the central panels depicting historical figures (beginning with St Victor and ending with King Henry VIII) associated with the abbey. Both the borders and the tracerysections of the windows are made up of late medieval fragments, while larger pieces of medieval glass are interspersed between the figurative windows.

The glazing was carried out by Arnold Wathen Robinson, who was also responsible for the war memorial windows on the north side of the nave, and for the scenes of the childhood of Christ in the Berkeley Chapel. Born in Gloucestershire in 1888, Robinson was an apprentice to Christopher Whall between 1906 and 1912, after which hereturned to the West Country, where he eventually took over the Bristol firm Bell & Co. in 1923.

The cloister scheme affords the viewer the unusual opportunity to see medieval glass at close quarters. The rich variety of medieval artistry and craftsmanship can be discerned in the jewel-like colouring of the decorative elements, the sensitive handling of faces and hands, and the humour evident in the rendering of animals. Two notable details include a close-up view of the face of an angel who is holding the chains of a thurible, and a pair of comedically portrayed sprites (above).

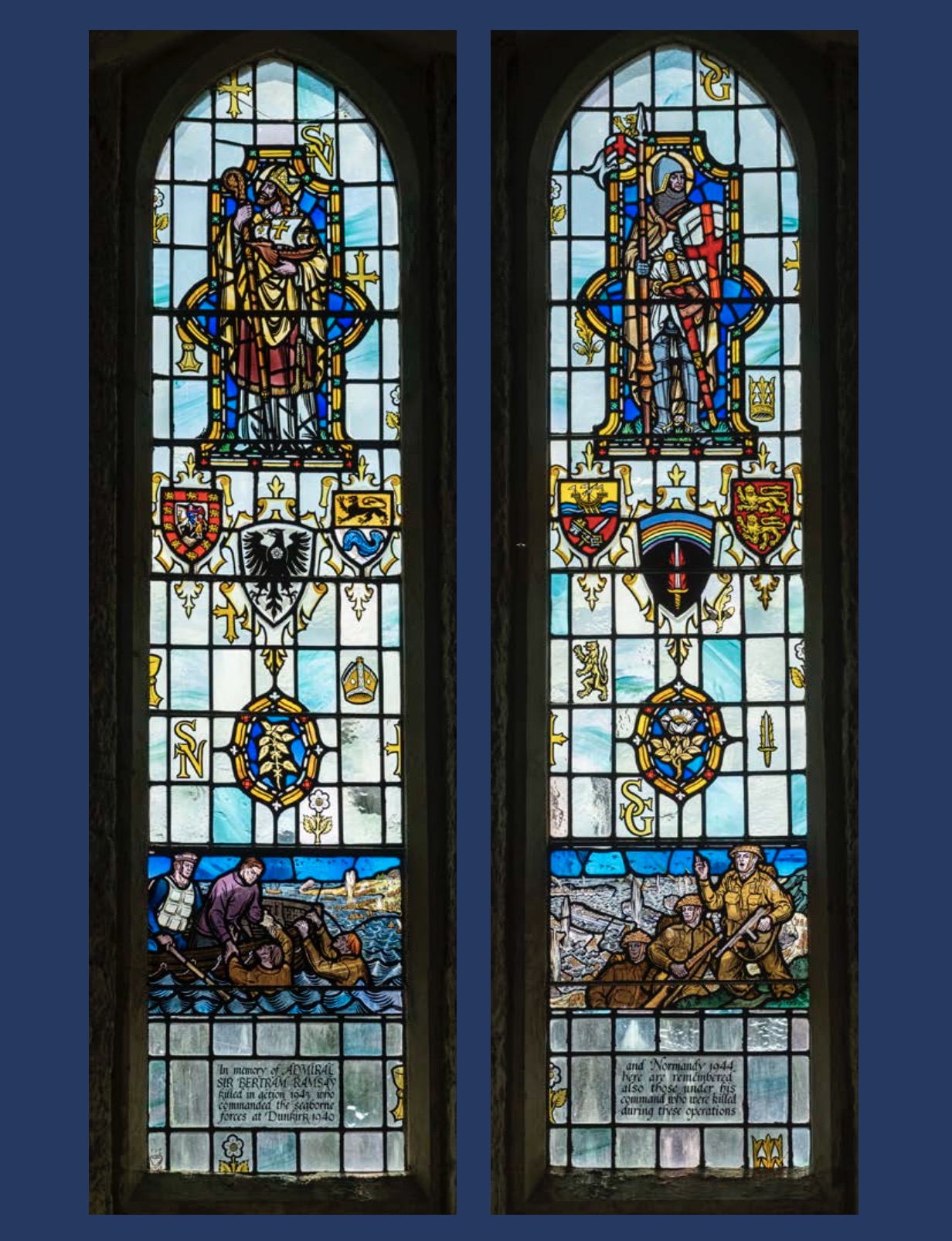

PORTSMOUTH CATHEDRAL – Dunkirk and D-Day Windows (1956)

Two windows by Edwards & Powell, south wall, Chapel of Healing and Reconciliation, 2.6 × 0.6 m (each window)

Portsmouth Cathedral is known as the ‘Cathedral of the Sea’, and the maritime history of Portsmouth is evident from a whole variety of memorials, windows and objects found within the building. A crucial moment in this history was the 1940 rescue of hundreds of thousands of soldiers from Dunkirk by the famous ‘little ships’. This was at the instigation of Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, who also commanded the seaborne forces for the D-Day landings of 1944.

In January 1945, with the victory of the Allies assured but the war not yet over, a plane carrying Ramsay and his staff crashed on take-off, killing everyone on board.

On the south side of Portsmouth Cathedral is the Chapel of Healing and Reconciliation, and windows there contain images of both Dunkirk and D-Day. These are also a memorial to Admiral Ramsay, and to those who served under his command. They were installed in 1956 by Carl Edwards and Hugh Powell’s glassmaking firm (whose makers’ mark, ‘E & P’ over a pestle and mortar, with the date 1955 beneath, is in the bottom left-hand corner of the Dunkirk Window).

The ‘SN’ immediately above the stained-glass image of Dunkirk is for St Nicholas, patron saint of sailors, while the ‘SG’ in the D-Day Window signifies St George, patron saint of soldiers. Adjacent to these initials are images of a nettle and a flower, which make reference to Hotspur’s speech in favour of courage and bold action in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1: ‘out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety’. Careful observers of the windows will note that, above the depiction of seaborne sailors and soldiers hemmed in by shellfire sending up huge plumes of water, the skies are full of aeroplanes. In this way all three services of the British Armed Forces are represented.

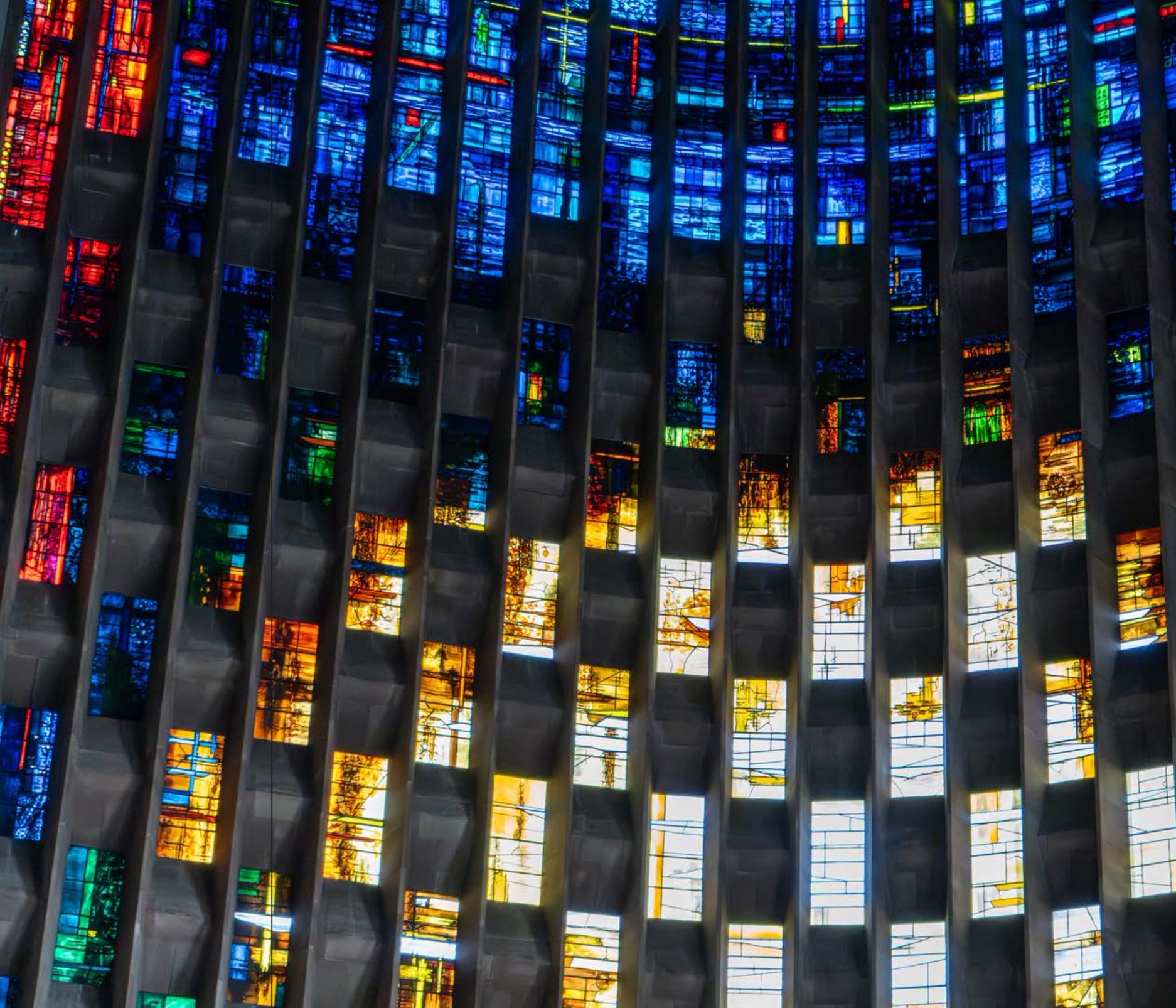

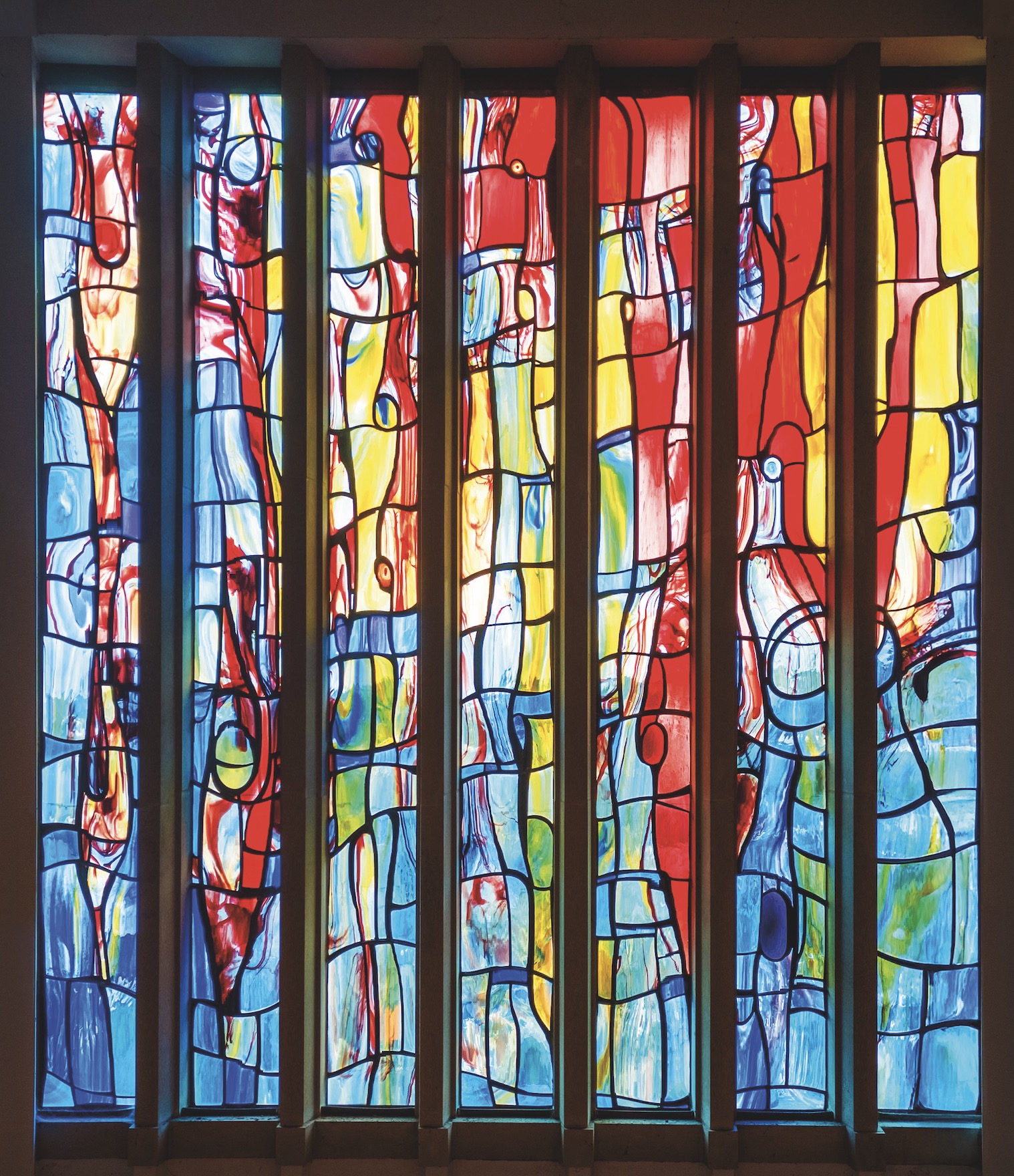

COVENTRY CATHEDRAL – Baptistery Window (1962)

198 colourful textured abstract panes occupying full height of bowed baptistery, designed by John Piper (1903–92) and made by Patrick Reyntiens (1925–2021), north-west end of nave, 17 × 26 m

The Coventry Cathedral Baptistery Window is one of the country’s finest, and largest, twentieth-century stained-glass windows. It is made up of 198 lights that combine to produce a breathtaking explosion of colour. The lights curve slightly around a small platform that supports the font, which is made of a rough-hewn boulder from a hillside outside Bethlehem.

Each pane of the window faithfully reproduces John Piper’s richly textured designs, which included different forms of collage, layers of paint, and wax resists. So skilfully does Patrick Reyntiens’s glasswork bring the designs – including Piper’s apparently random blobs of colour – to life that the result is almost mobilein its intensity. The final installation is commonly referred to as the Piper/Reyntiens window, on the grounds that the window’s fabrication is as significant to its impact as the design.

Like most other coloured glass in the Cathedral, the Baptistery Window is abstract. The emphasis placed on the ‘blaze of light’ in the centre of the window conveys the glory of God in the sacrament of Baptism. Above are the deep blues of the heavens, and below are the varied greens of the earth. The best way to mediate the window’s overwhelming impact is to stand far back – to look at it from across the space of the rear of the nave – and then proceed to walk up and engage with one of the lower panes in detail. The variety of colour in the individual lights speaks of the beautiful, complex diversity that the Cathedral celebrates in its call to reconciliation. These lights come together in a form that, in the words of Bishop Cuthbert Bardsley, ‘expressed faith in an entirely new way[,] with the subject emerging through the glory of the colour’.

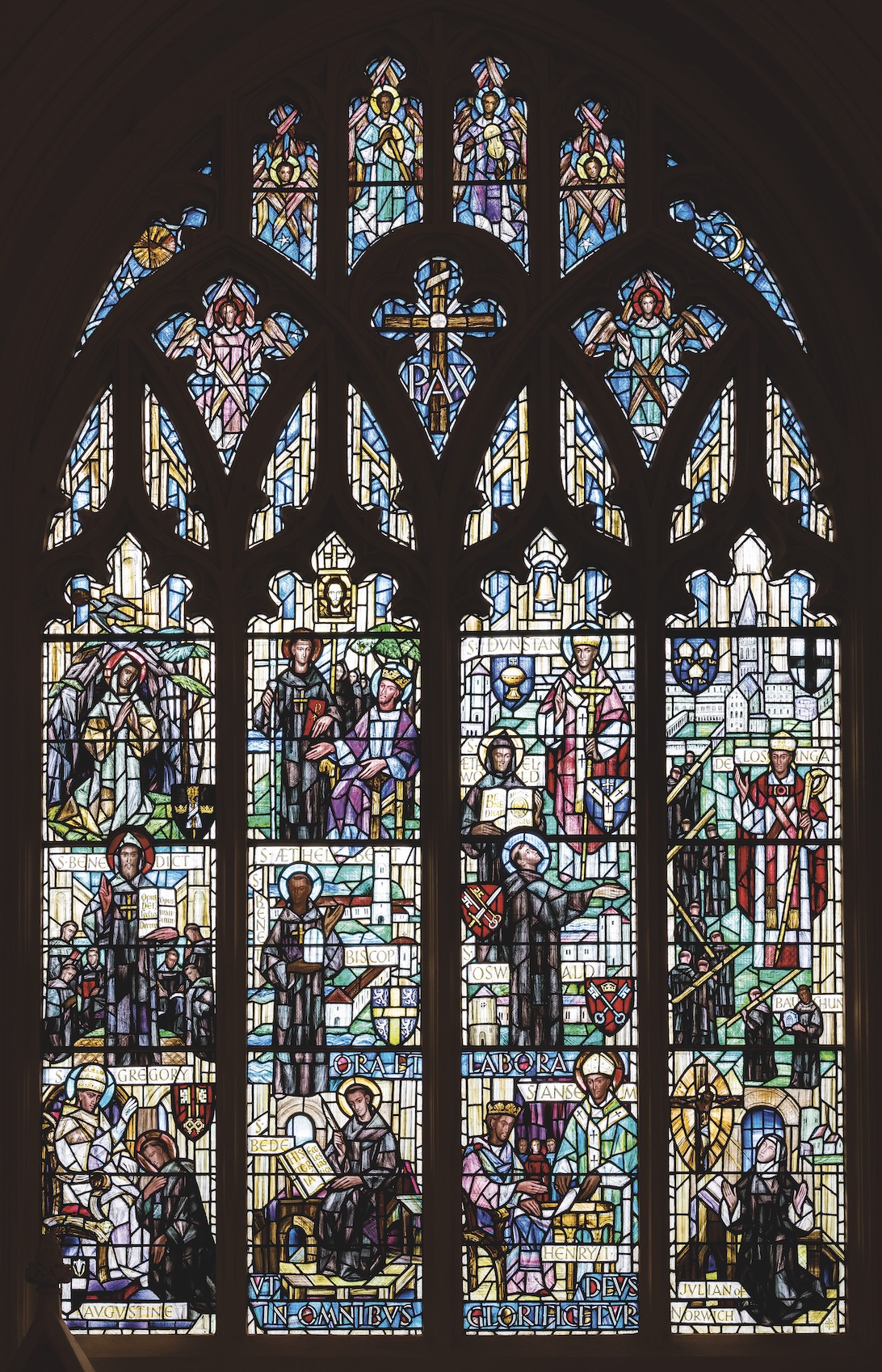

NORWICH CATHEDRAL – Benedictines in England Window (1964)

Designed by Moira Forsyth (1905–91) and made by Dennis King (1912–95) of King & Sons, Bauchun Lady Chapel, window 5.8 × 3.5 m

Of the twenty medieval cathedrals in England, nine were Benedictine priories. The phenomenon of monastic cathedrals was virtually unique to England and had a profound impact on other English cathedrals, both before and after the dissolution of the monasteries.

Norwich was the last of the monastic cathedrals to be founded (in 1096) and the first to surrender to the Crown (in 1538) – the latter ensuring a complete continuity of personnel between the last Prior and his monks and the first Dean and his canons. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, the mission and ministry of Norwich Cathedral have been decisively shaped by its Benedictine heritage.

The Benedictine Window is a strong statement of the importance of that inheritance. It is located in the fourteenth-century Bauchun Chapel of Our Lady of Pity (named for its benefactor, William Bauchun, a merchant and lay servant of the Priory, who is depicted holding the chapel). In accordance with the tradition of narrative historia, the window traces the development of Benedictine monasticism from Benedict’s career as a young hermit to the commissioning of Augustine by the Benedictine Pope Gregory the Great (597) and the accomplishments of notable monastics in England. Benedictine contributions to the visual arts figure prominently: note St Augustine’s icon of Christ and St Æthelwold holding his Benedictional. The bell adjacent to St Dunstan is a reminder of his skill as a metalsmith and musician; St Benet Biscop, the builder of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow, is shown with the window glazing he introduced.

It is worth noticing two misattributions: neither Bauchun nor Julian of Norwich, shown habited here, belonged to a religious order. This window was among Moira Forsyth’s own favourites, in part because of the importance of leading in the design, and in part because of her love of lettering.

DERBY CATHEDRAL – All Souls and All Saints Windows (1964)

Two stained-glass windows designed by Ceri Richards (1903–71) and made by Patrick Reyntiens (1925–2021), nave East Windows, 5.25 × 2 m

Visitors to Derby Cathedral are immediately drawn into a space that is suffused with daylight, thanks to the clear glass on the north and south walls and in the retrochoir. The interplay of light, colour and beauty make a profound impact – after which the visitor encounters the only two stained-glass windows in the early Georgian nave.They bring drama, colour and theological depth to Derby Cathedral’s worship.

These windows were installed in 1964. They were designed by the celebrated artist Ceri Richards and made by Patrick Reyntiens. Their sharp blue and yellow colours and their fluent abstract shapes and patterns are more basic and elemental than anything else in the Cathedral, giving the viewer a glimpse of the primordial struggle between darkness and light. The harmony of the right-hand window expresses the triumph of light over darkness and the reconciliation of all creation through Christ, who is depicted through the emergence of a cross.

In the All Souls Window on the left-hand side, Richards offers a meditation on the soul of humanity emerging from its physical limitations. We see this process reaching its consummation in the right-hand All Saints Window (its name being a reference to the Cathedral building’s tenth-century designation as the Collegiate Church of All Saints).

The blues and yellows pick up the colouring of the famous metal-work screen in Derby Cathedral, which was executed by the Derby- based early Georgian ironworker Robert Bakewell. The windows in the north and south aisles and Bakewell’s chancel screen together offer the worshipper an integrated view across the breadth of the nave. They speak eloquently of both the gift of our humanity and the experience of being lifted to the divine through the Holy Eucharist.

MANCHESTER CATHEDRAL – West Windows, including St George Window (1972–95)

Five stained-glass windows, including the first-completed St George Window (1972), 4.7 × 2.25 m, all by Antony Hollaway (1928–2000), set in Perpendicular-style windows along west façade of the nave

Out of terrible tragedy, new beauty can sometimes emerge. In December 1940 Manchester Cathedral endured a German bombing attack that shattered all of its windowglass. Restoration of the main fabric of the Cathedral was complete by 1955, but the replacement of the building’s stained glass only went as far as the use of a traditional design for the East Window above the Lady Chapel.

In the 1960s, however, a decision was made to use contemporary designs for the remaining windows, with Antony Hollaway being commissioned (with support ofcathedral architect Henry Fairhurst) to design five windows along the west façade of the nave. The patronal saints St George, St Mary and St Denys are bookended in this series by depictions of the Creation and Revelation; the design and installation took place between 1972 and 1995.

The five windows were produced in deep hues to take account of their west-facing location. They ought to be read together for full insight into their splendour and grandeur,but each is a masterpiece in its own right. The four-lightwindow celebrating St George, the first of the five to be completed, was funded by Mrs Frances Anderson in memory of her husband. An off-centre white cross for England is overlaid by a full-height scarlet cross for St George, the strength and verticality of which are derived from the closegrouping of small, narrow slivers of rose and pink. These two crosses drawthe eye to the forked tail of the dragon to the left and overlay the sinuousbody writhing at the bottom of the window. Small, pebble-like panes to the right, representing the dragon’s scales, cluster below the outstretched bar of the red cross. This, the most representational design of the five windows, leads satisfyingly into the more abstract designs of the other four.

RIPON CATHEDRAL – St Wilfrid Window (1977)

Harry Harvey (1922–2011), east wall of north transept, 2.9 × 1.2 m

This striking window is by Harry Harvey, a renowned York artist, and dates from 1977. It was given in memory of Charles Sykes, who was a successful businessman in the West Yorkshire wool trade.

It illustrates the life of St Wilfrid, builder of the first church on this site in AD 672 and forever associated with Ripon. Remarkably, Wilfrid’s crypt survives as the oldest complete structure of any English cathedral.

Bearing a sword and shield is the Archangel Michael, who was linked with key moments in Wilfrid’s life. In the centre is the imposing figure of Wilfrid as Bishop of Northumbria. Around him in the fragmented glass are the symbols of the four Evangelists: to the left the head of a man (Matthew) and that of a lion (Mark); to the right the head of an ox (Luke) and that of an eagle (John).

A left-hand panel features the word ‘Lindisfarne’ written vertically beside a scene of the young Wilfrid being sent by Eanflæd, Queen of Northumbria, to study and serve at Lindisfarne, where he lived for four years from the age of fourteen.

On the right are St Andrew and St Peter, each with his name written vertically. Wilfrid dedicated his Ripon church to St Peter and his church in Hexham to St Andrew.

At the bottom left is a scene from Wilfrid’s birth, when his home was seen to be on fire; neighbours rushed with buckets to douse the flames, only to learn from a maidservant that all was well – the flames were a heavenly sign of the child’s holy calling.

The final scene on the right illustrates the story of Wilfrid teaching the South Saxons to fish at a time of acute famine. Wilfrid was successful inconverting the last pagan kingdom in the country to Christianity.

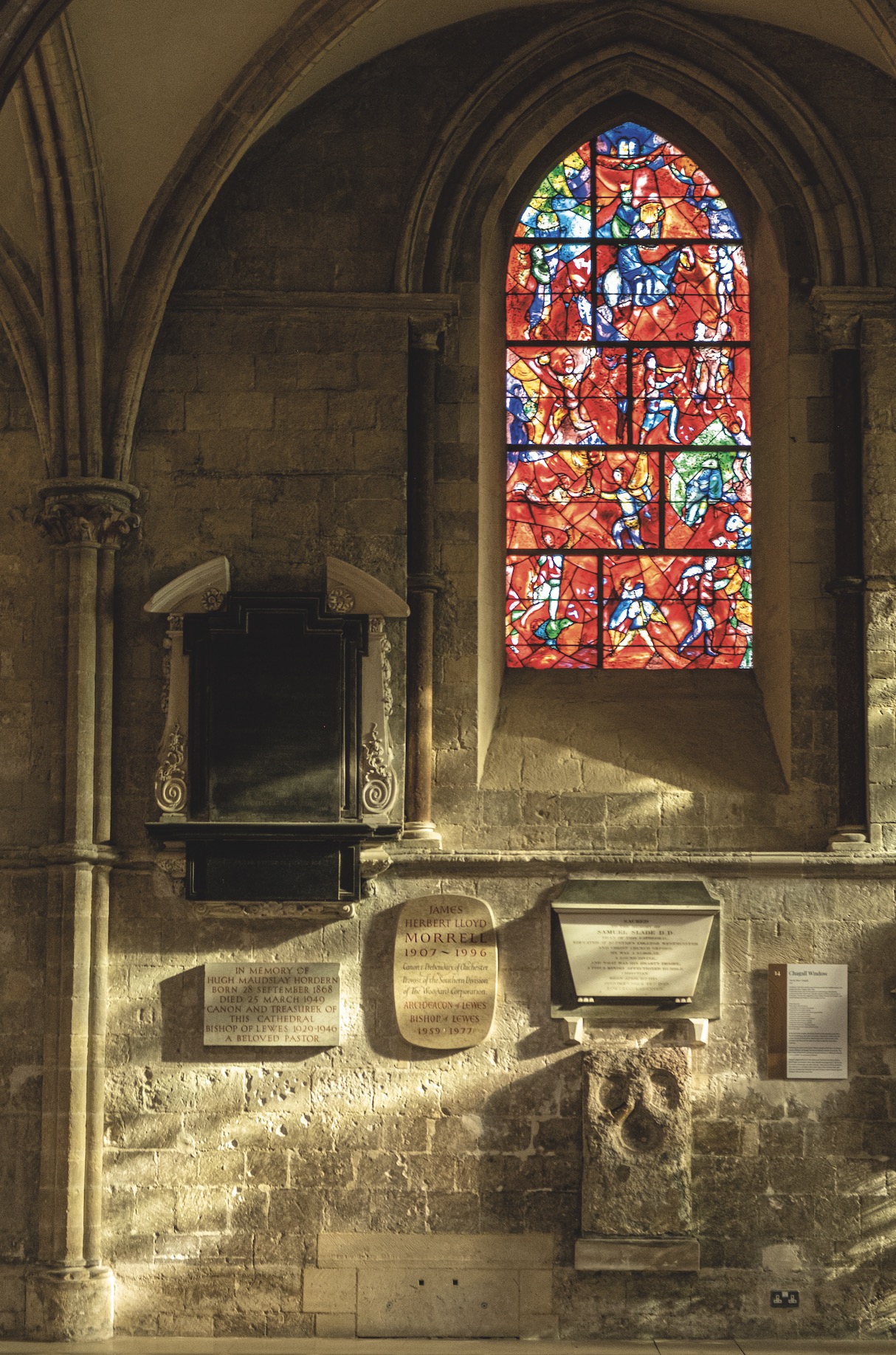

CHICHESTER CATHEDRAL – Chagall Window (1978)

Commissioned by Dean Walter Hussey, designed by Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and made by Charles Marq (1923–2006) at Reims Cathedral, north choir aisle, c.3.5 × 1.25 m

Dean Walter Hussey was responsible for commissioning a number of Modernist artists to produce works for the Church: both at Chichester Cathedral and while he was a vicar in Northampton. He believed that these artists brought a dignity and force to their art that could help the Church communicate its message.

One of his Chichester commissions was a stained-glass window from Marc Chagall. It came about after Hussey saw a set of stained- glass windows produced by Chagall for a hospital synagogue in Jerusalem. These windows were displayed in the Louvre in Paris in 1961 before being shipped to their ultimate home.

The Chichester window is predominantly red in colour, with a number of small figures scattered throughout. Some of these are people, some are animals, and a few are part-animal and part-human. Most are singing or playing musical instruments, recalling the universal outpouring of praise described in Psalm 150. The figures appear to be floating, a motif which is typical of Chagall’s work and which goes back to the folk imagery of his childhood home in rural Russia.

Hussey’s theme for the window was ‘The Arts to the Glory of God’, and this brightly coloured window certainly meets that description. Chagall was aware of the spiritual depth of his stained glass; he said in an interview that ‘every colour should encourage prayer’, and he saw his work in stained glass as a form of prayer in itself. The window was made in the workshop of Charles Marq at Reims Cathedral, with Chagall working on it in the studio at his home. It was delayed because the requisite red glass was only manufactured twice a year, in June and December. When the window was finally completed and installed, Hussey, now retired, returned to Chichester for the unveiling on 6 October 1978.

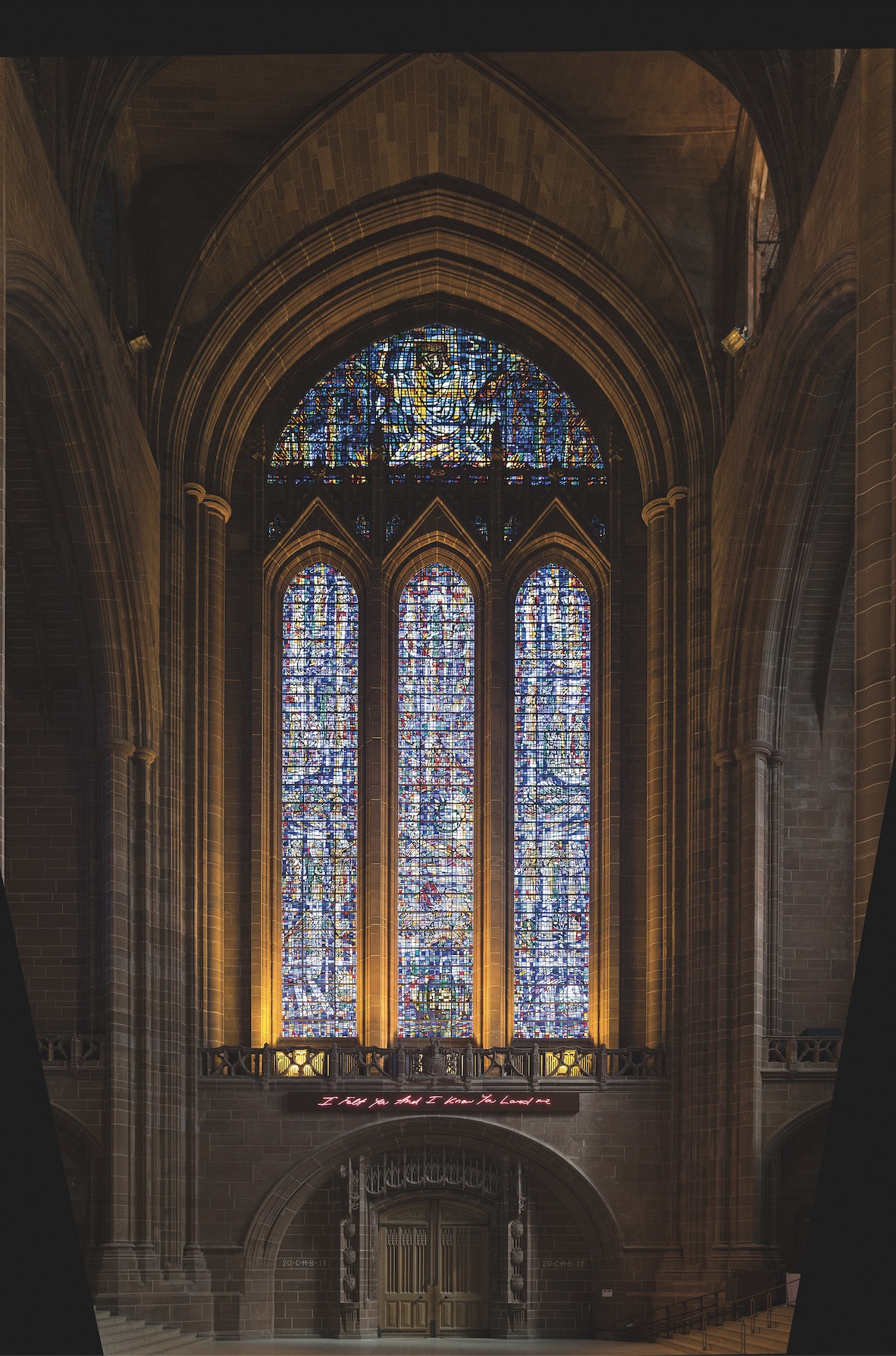

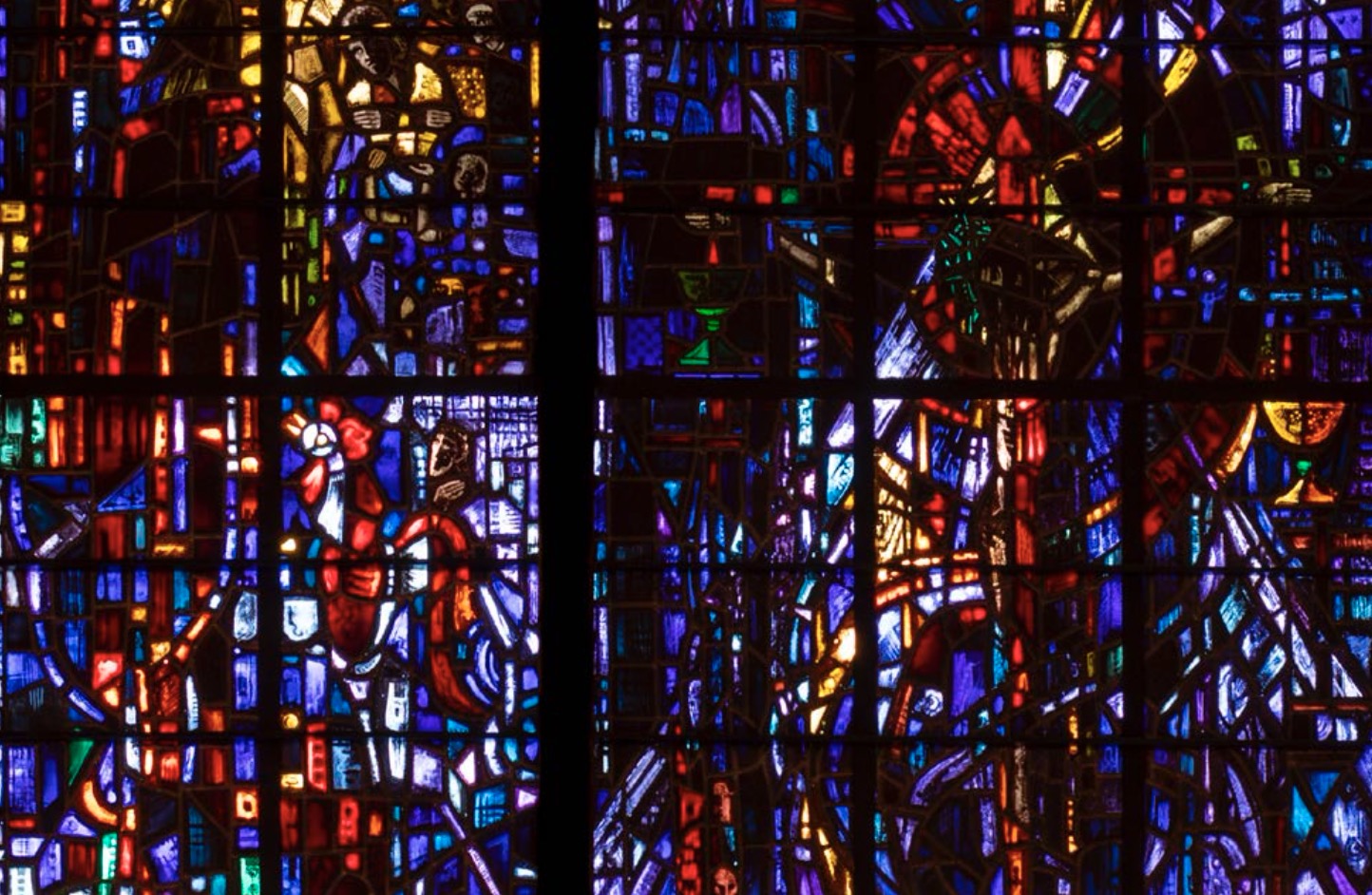

LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL – Benedicite or Great West Window (1979)

Handmade English glass in three lancets (16 m high) and a fan light, by Carl Edwards (1914–85), made at the Glass House, Fulham, spans 149 m2 of glass

Work began on the Great West Window in the 1970s as the Cathedral was nearing completion. The subject of the window is the Benedicite, the Canticle to the Apocrypha, which begins ‘O all ye works of the Lord, bless ye the Lord.’

The stained glass consists of three lights, tracery, and a large fan light. The window covers approximately 149 square metres, more than twenty-three times the surface area of one of the nave windows. The base of the centre light depicts aMersey scene, showing both the Royal Liver Building and the Mersey Ferry.

The artist Carl Edwards wrote the following description of the window: ‘It is the treatment and disposition of the colour … where the difference is greatest when compared to the other windows in the Cathedral. Great vertical passages of colour run the entire length of the lights, and parallel with the blue run long vertical passages of gold, which issue from the large figure of our Lord in the fanlight. Reds and greens and other contrasting tints and hues relieve the illustrated parts of the Canticle which interrupt the vertical lines of blue and gold.

The treatment, types of glass and use of thick leads follow the techniques used for the nave windows. English handmade glass is used because its varying texture and thickness mean that the window’s colours are always capable of attracting attention, however indifferent the light may be on a dull winter’s day. The surface of the glass is kept free from half-tones, allowing the maximum amount of light to penetrate the Cathedral.

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL – Prisoners of Conscience Window (1980)

Vibrant blue stained glass in five lancet windows designed by Gabriel Loire (1904–96), made at Maison Lorin studio in Chartres, Trinity Chapel at east end of the Cathedral, 5.8 × 1.5 m (central light) and 4.9 × 0.9 m (sides)

‘Who else in this 20th century of frightfulness could be more appropriately commemorated in a new window in an ancient cathedral than the men and women who, at the cost of mental anguish, physical pain, spiritual humiliation, isolation or premature death, have upheld by nonviolent witness the dignity of the human person against falsehood and tyranny?’ – Dean Sydney Evans

On his appointment as Dean of Salisbury in 1977, friends of Sydney Evans expressed their interest in what he would do about the Cathedral’s interior.‘Once inside you feel that somehow the glory has departed,’ one complained. Evans attributed this feeling to the muted colours of the Chilmark limestone and Purbeck marble from which the Cathedral is built. He determined that a new window would transform the experience of anyone gazing at the unimpeded vista from west to east – catching, as he put it, ‘the eye of the morning and the eye of the visitor and the inner eye of the worshipper’.

For four decades Gabriel Loire’s window has done just that, with its gorgeous colour glowing gently at the Cathedral’s east end on the gloomiest of winter afternoons. Working on the outskirts of Chartres, Loire was well acquainted with the rich shades of blue that characterise Chartres Cathedral’s unparalleled medieval windows. These he brought to Salisbury, to stunning effect.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Evans should have chosen prisoners of conscience as the subject of the window. Salisbury treasures its copy of Magna Carta, the first charter that attempted to curb the tyranny of the monarch. The window honours the modern victims of unchecked tyranny. Their haunting faces fill the north and south lancets. And in the centre the window recalls the viewer to Christ, who suffered gross injustice at the hands of men, and whose sacrifice, glorified by God, offers hope to all.

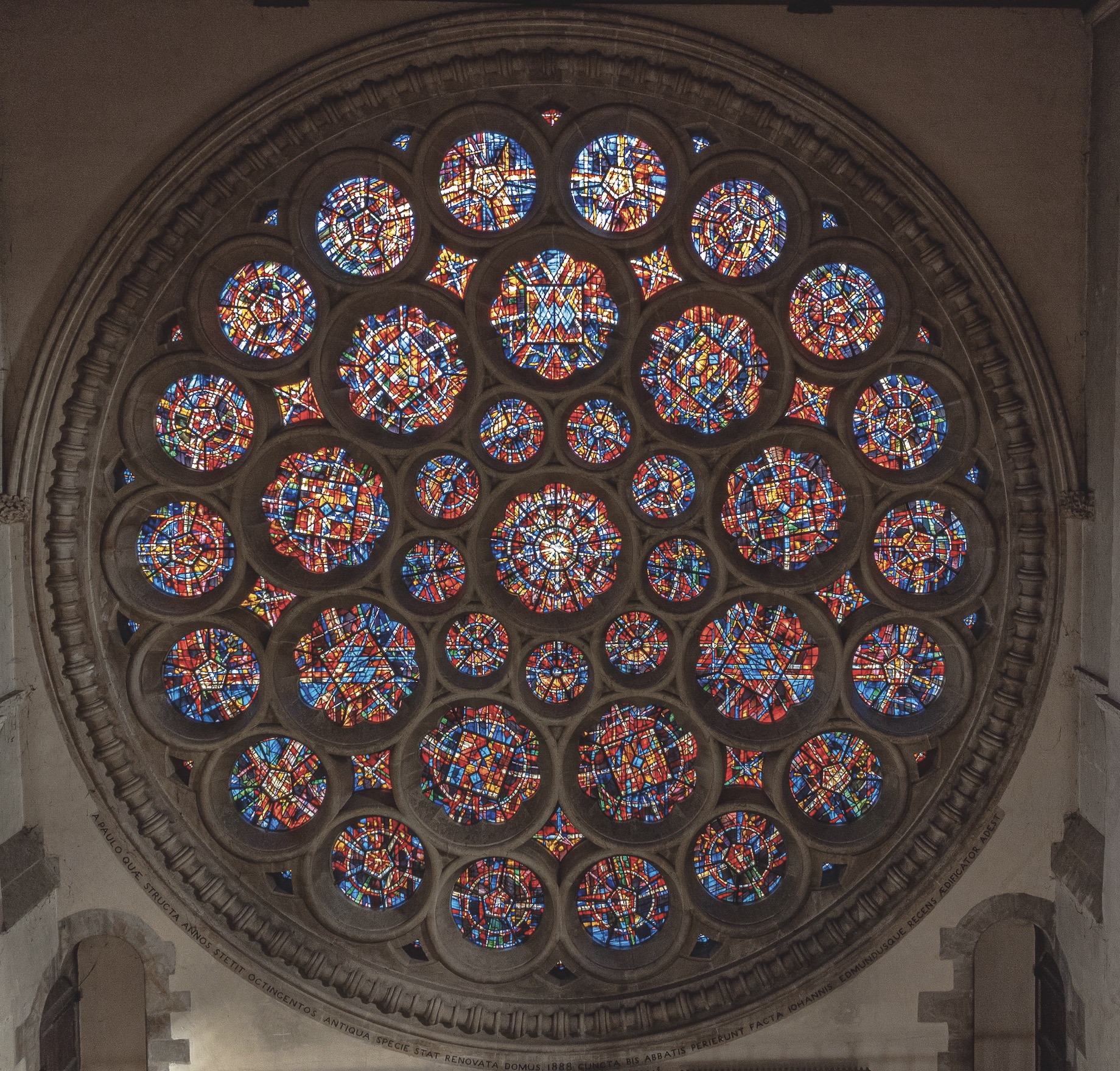

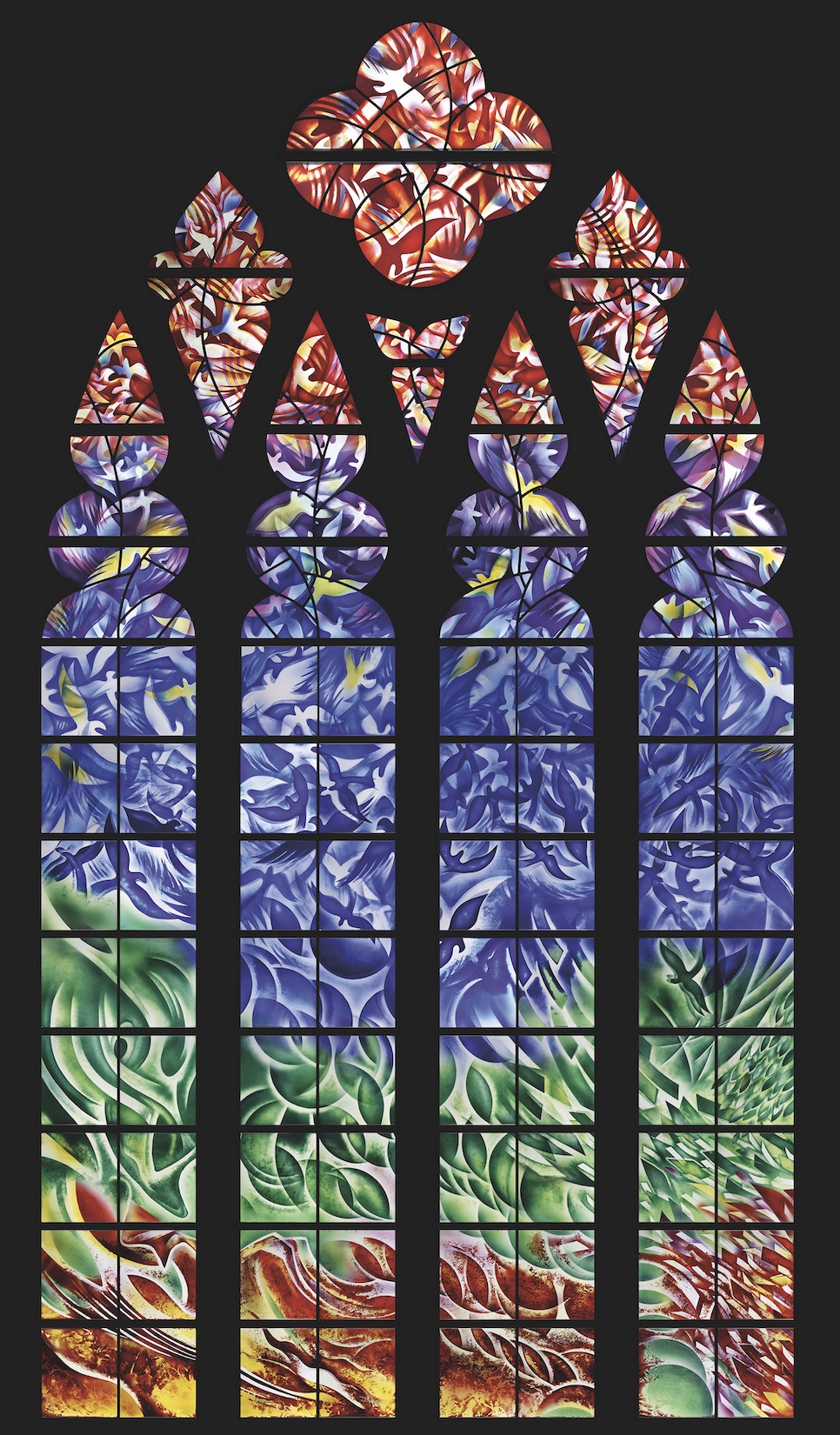

ST ALBANS CATHEDRAL – Rose Window (1989)

Sixty-four openings of 18,000 pieces of hand-blown ‘antique glass’ as creation and the created universe, Alan Younger (1933–2004), north transept, diameter 9.1 m

Lord Grimthorpe’s heavy, clear-glazed Rose Window at St Albans Cathedral was replaced in 1989 by a glorious explosion of colour created by Alan Younger.

The great weight of Grimthorpe’s masonry immediately suggested to Younger a rich, fully coloured scheme using tiny pieces of glass to achieve a jewel-like effect. The modern window is formed of sixty-four openings and contains 18,000 pieces of hand-blown glass (known as antique glass).

Rose windows serve as symbols of creation and of the created universe. Younger chose to explore this theme using basic geometric shapes such as squares, circles and triangles. Their arrangement was informed by a simple mathematical idea from the Middle Ages: that to multiply three by four is, in a mystical sense, to infuse matter (the window’s four major circles could represent the elements) with the spirit (the window’s large triangle symbolises the Trinity). The resulting number twelve signifies order and the universal Church.

Younger’s hope was that the window would make an immediate impact upon anyone entering the building, while also rewarding the kind of extended observation that reveals the window’s intricate rhythms and mathematical groupings.

The colour, emphasis and mood of the Rose are constantly shifting as a result of changes in the light, both over the course of a single day and as one season transitions into another. The dark glazing and wire protection grill visible from the outside have led to the Rose being called the ‘Magic Window’ by the local population; the kaleidoscope of colour high in the north transept only becomes apparent when you enter the Cathedral. The window was dedicated by Diana, Princess of Wales.

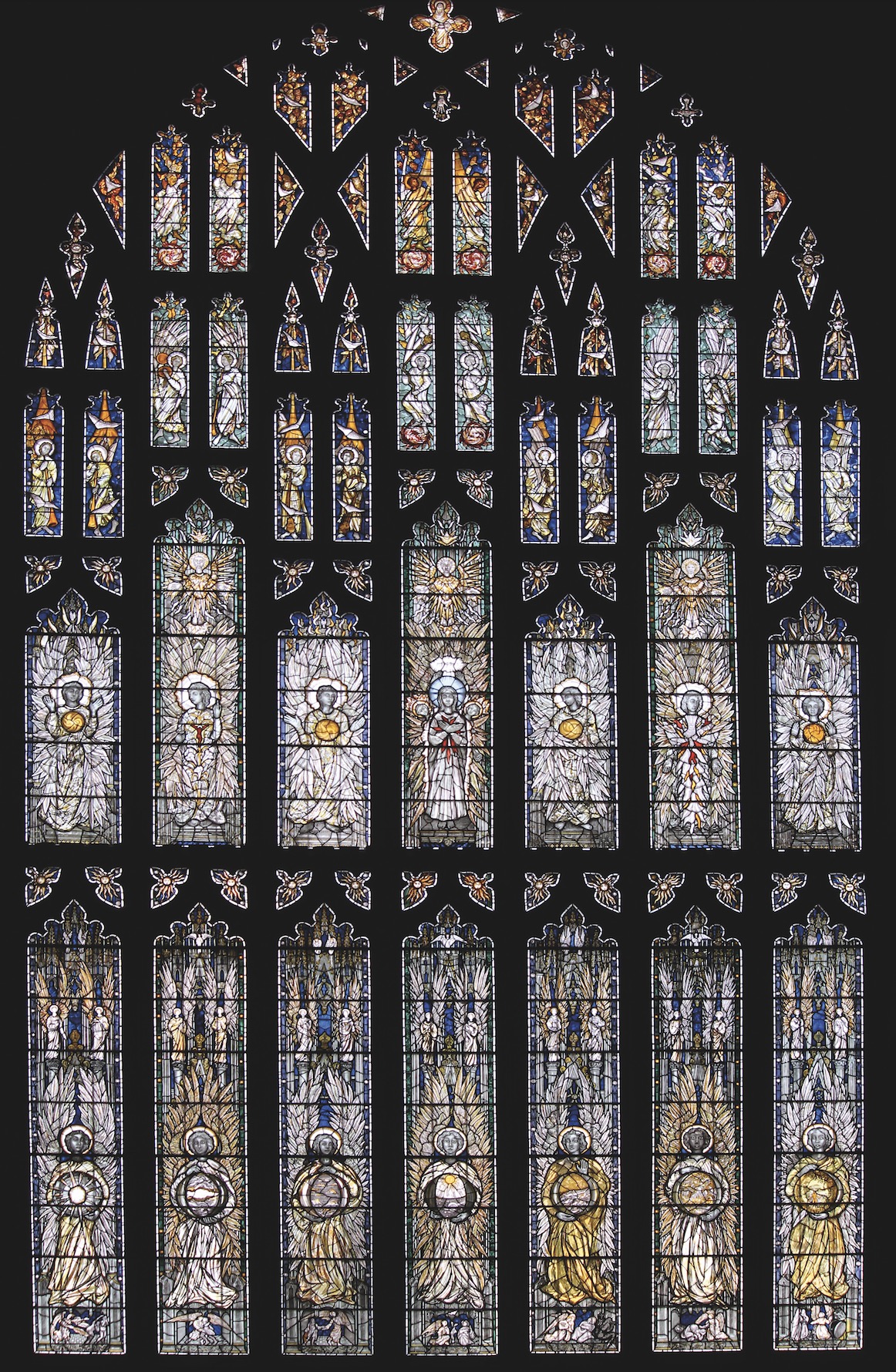

SOUTHWELL MINSTER – Angel Window or Great West Window (1996)

Grisaille glass window conceived by Martin Stancliffe (1944–2025), designed by Patrick Reyntiens (1925–2021) and made by Keith Barley (b. 1951) at Barley Studio in York, 17 × 10 m

The Perpendicular Great West Window of Southwell Minster came alive in 1996, when Patrick Reyntiens filled it with scores of light-filled angelic intelligences, according to adesign suggested by architect Martin Stancliffe. The grisaille glass, with its subtle shading and layering, allows the sun to blaze through the window. Reyntiens perceived a triadic structure in the stone tracery, and sought to suggest a kind of trinitarian circling in his groupings of figures.

The angels in the lower of two rows look out at us quizzically as they mediate the days of Creation – from the explosion of light on the left, to the appearance of dry land and the separation of day and night, to the creation of birds, fishes, animals and, finally, humankind. Nestling beneath are tiny scenes of angelic intervention from Scripture. From left to right we have an angel expelling Adam and Eve from Eden, Jacob wrestling with his angel, Tobias being led by an angel, the Annunciation, Christ in the wilderness, Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, and finally the angel appearing to the two Marys at the sepulchre.

Centred among the angels is the smaller figure of the Minster’s patron, the Virgin Mary. We can see the Holy Spirit brooding above her, as well as the words ‘I am who I am’ from the burning bush (Exodus 3:14) written in Hebrew (see right). The Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55) is written around the border. Above Mary, the angels become more active as their ninefold order proceeds ever nearer to the divine hand at the summit: some fling incense with abandon, while others trumpet or just wheel, coruscating like fireworks. The blue of the wise cherubim and the red of the loving seraphim predominate at the upper levels. As Reyntiens noted, ‘It is all just joy and worship’.

BLACKBURN CATHEDRAL – Cathedral Lantern Glass (1999)

Fifty-six panes of vibrant coloured glass designed by Linda Hadfield (b. 1957) for Laurence King’s (1907–81) 1950s Lantern Tower

The biblical theme of Christ as the Light of the World reaches new heights in the Lantern Tower – a striking pillar of light crowning Blackburn Cathedral.

At the east end of the building are the sanctuary, transepts and eastern chapels. Above the central altar is the ‘Corona’ – the Crown of Thorns – designed as the ‘crowning glory’ of the new Cathedral, which was consecrated in 1977. The original structure, designed by Laurence King in the 1950s, was made of concrete, to which was affixed mosaic-patterned stained glass designed by John Hayward.

Neither material stood the test of time, however, and in 1998 the Lantern Tower was rebuilt in natural stone, incorporating fifty-six new panes of traditionally made stained glass. Designed by Linda Hadfield, the new glasswork explores the theme of the Spirit of God, with dominant elements of water and fire.

Hadfield wrote of her design for the glass, ‘it encapsulates the warm reds of the morning sun contrasting through various shades to the cool blues of the evening shadows… at night, when lit, the Lantern will be a welcoming beacon for all, a pillar of fire glowing to the honour of God, mingling with the light of Heaven to dispel the darkness of the night.

When illuminated from within, the Lantern Tower shines over the town, the diocese and the county beyond, serving as both a beacon of light and a symbol of hope and trust in God. On bright days, a kaleidoscope of oranges, reds, yellows and blues cascade onto the Cathedral’s pillars, arches and floors, moving around the building as the sun changes position.

ELY CATHEDRAL – Processional Way Windows (2000)

Fourteen geometric grisaille lights, 1.8 x 1.6 m, designed by Helen Whittaker (b. 1974) and made by Barley Studio, for the 2000 Processional Way by Jane Kennedy (b. 1953), linking the Lady Chapel to the Cathedral, three blocks of four lights and two lancets

The Processional Way at Ely Cathedral was built in 2000. The first major addition to the Cathedral since the Reformation, it recreates the lost medieval passageway that once connected the Lady Chapel to the Cathedral. It was designed by Jane Kennedy, then Surveyor to the Fabric, to harmonise with its surroundings and reflect Ely’s heritage.

The windows were designed by Helen Whittaker and made by Barley Studio of York. They were one of Whittaker’s first commissions after she joined the studio. There are fourteen geometric lights, which together are intended as a timeless design sympathetic to the surrounding architecture. As with medieval grisaille (from the French gris, meaning grey), they incorporate white (clear) glass with geometric patterns and some coloured glass – predominantly grey, green and yellow. All ofthese components have medieval origins. Grisaille windows were developed during the thirteenth century and let in more light than pot-metal glass, thereby enhancing their architectural settings.Their purpose was both decorative and functional.

Whittaker’s aim was that the windows should not be a focal point, but that they should rather encourage people to move through the Processional Way. She used her training in geometry to create circles that would guide visitors through the space. All of the geometric patterns are framed with lead lines and delicate painted foliage. Incorporated into the design are small roundels containing images of Ely’s founding saint, St Etheldreda (shown with her crown and crozier), and symbols of the Virgin Mary (the monogram MR and a fleur-de-lis), the Dean and Chapter of Ely (three keys) and the Diocese of Ely (three crowns – said to represent the first three royal Abbesses of Ely).

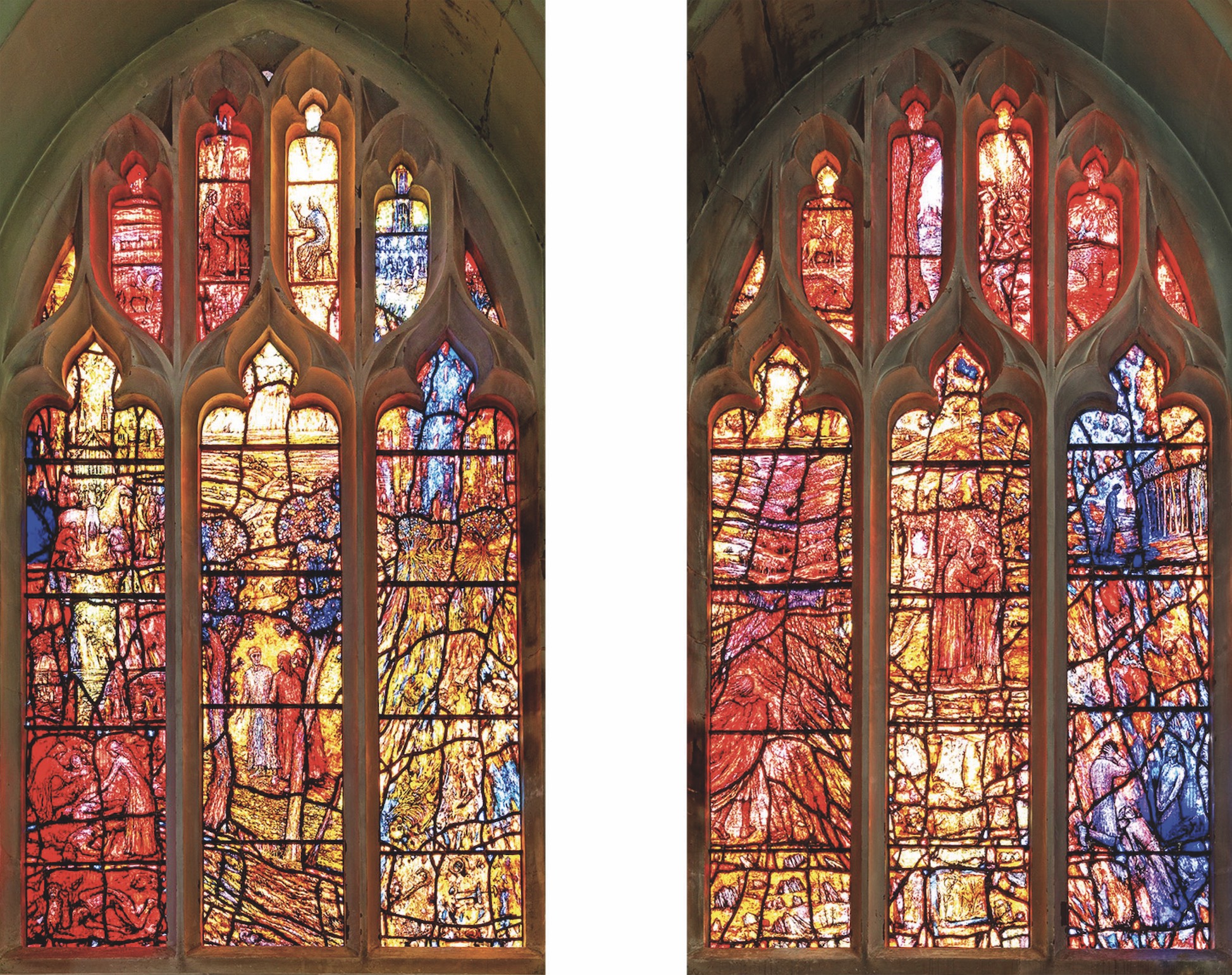

LEICESTER CATHEDRAL – Redemption Windows (2016)

Two stained, painted and etched windows in three vertical panels by Thomas Denny (b. 1956), St Katherine’s Chapel near King Richard III’s tomb, 3.45 × 2.03 m

In Thomas Denny’s 2016 Redemption Windows we see King Richard III – who is buried at Leicester Cathedral – and are invited to contemplate the moment of his final humiliation as he is slung naked over the back of a horse. Symbols of power lie discarded, while Christ offers the grief-stricken Richard the consolation he yearned for in the final chapters of his life. In an adjacent light, a lone figure, presumably Richard, embarks on a hazardous journey through the valley of the shadow of death, with a tangle of thorns and woodland edged by camping soldiers perhaps foretelling his end.

In an evocation of the Road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13–35), Christ sports a medieval hairstyle, while the depicted landscape is local to the Cathedral. History is no longer rooted in biblical times but is instead repeating itself, with time opening out so we can feel, in Denny’s words, ‘the potential for something extraordinary to happen at any time’. Denny’s windows are both revelatory and familiar, local and universal.

Red predominates. Ruminating on the lack of natural light in the north-facing chapel where the windows are housed, Denny noted the red glow reflected from the Buddhist Centre opposite – ‘one faith giving light generously to another’. This observation led Denny to the conclusion that red should dominate his palette, with blue, violet and green providing support.

Denny has said that the possibility of redemption and reconciliation is ‘at the heart of life and … of these two windows’. He was working at the same time on the Reconciliation Window installed in St John’s Church, Tralee in 2017. In Ireland the burden of history is a reality, and for Denny the two commissions became intertwined, with each reflecting a strong sense of history being animated.

DURHAM CATHEDRAL – Illumination Window (2019)

Window comprising sixty-four acid-etched and enamelled plates in four lights, with tracery above, by Mel Howse (b. 1968), north quire aisle near the Shrine of St Cuthbert, 7 × 4 m

In the north quire aisle of Durham Cathedral, opposite the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a window commemorating the life of Sara Pilkington, a Combined Arts student from Durham University. Following Sara’s death from a cardiac-related condition, her parents worked with the Cathedral to create this striking memorial. Designed and made by the award-winning glass artist Mel Howse, the Illumination Window was dedicated on 11 May 2019.

The artist’s brief was to create a window that would be ‘beautiful, meaningful, uplifting, spiritual and celebratory’. There is no black in the design; instead, a white structure runs through a palette of glowing colours, which Howse describes as ‘a fitting symbol in memory of Sara … a young and vibrant woman’. Sixty-four etched and enamelled glass plates continue upwards into shaped tracery lights. The glasswork was produced using hand-worked techniques including acid-etching and enamelling, with minimal use being made of lead.

The window’s innovative, semi-abstract design is inspired by Cuthbert’s island sanctuary of Inner Farne. Howse imagined Cuthbert as being surrounded by ever-shifting weather, water and birdlife. Patterns, shapes and colours change with the light, creating flowing, liquid textures. The name ‘Illumination’ was chosen in order to suggest the bringing of light and understanding – physically, spiritually and academically. It also references the Lindisfarne Gospels, an illuminated manuscript that was produced in the saint’s honour.

Overlooking Palace Green, the Illumination Window both commemorates Sara and celebrates the special, historic relationship between Cathedral and University. A place for moments of quiet reflection in times of need or, equally, joy, it has become a focal point for the Cathedral’s student ministry. From a place of darkness and sorrow comes light, colour and love.

Part 1 – The Middle Ages and the Reformation

Part 2 – The Long Nineteenth Century

Part 3 – The Modern Age

Picture credits – York Glaziers Trust © Chapter of York; David Brook; Andy Marshall; Mel Howse and Vitreous Art Ltd; Portsmouth Cathedral; Marcus Green; Lichfield Cathedral; The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral; Dan Beal; Lynne Alcott Kogel; Wells Cathedral; Holy Well Glass; Kevin Lewis; Tom Soper Photography; Rob Scott; Dean and Chapter of Christ Church, Oxford; Gordon Plumb; Winchester Cathedral; Janet Gough; Kevin Caldwell © Off the Rails Australasia Pty Ltd; Steven Jugg; Declan Spreadbury/Salisbury Cathedral; Gordon Taylor; Bradford Cathedral/Philip Lickley; Chris Parkinson; Gill Poole; Chris Hutt; Paul Barker; Christopher Guy/Worcester Cathedral; Mark Charter; © David Whyman; Clive Tanner; Peterborough Cathedral; Bill Smith/Norwich Cathedral; Peter Hildebrand/Visit Stained Glass; Luke Watson; Patrick Fitzsimons; Bristol Cathedral; David Pratt; Aaron Law; Manchester Cathedral/Nathan Whittaker; Liverpool Cathedral; Gareth Jones Photography; Salisbury Cathedral; St Albans Cathedral; Dr Chris Brooke; Southwell Cathedral Chapter; Blackburn Cathedral; Richard Jarvis and Aidan McRae Thomson of Norgrove Studios Ltd.